Share this article

Climate Change Could Increase Spread of Diseases

Climate change increases the likelihood of diseases spreading to new places and new hosts across the world, according to Daniel Brooks, a professor emeritus at the University of Toronto Department of Ecology and Evolution who has been studying emerging diseases for more than 35 years.

Determining how emerging disease come about and spread to different species is like figuring out a murder mystery, Brooks said. And, much like a murder mystery novel, the idea is to find out who has the means and who has the opportunity to commit the crime — in this case, a pathogen jumping to a new host, which is the definition of an emerging disease.

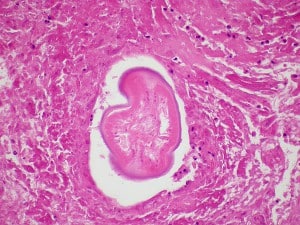

The parasite Dirofilaria immitis is pictured above. D. immitis which is also known as “dog heartworm” is an example of an emerging disease that has not only moved to new locations but also began infecting more species including humans.

Image Credit: Yale Rosen via Flickr

Based on their research, Brooks and his colleagues found the main assumption about parasites and host relations that many scientific theories are based on, is not accurate. Scientists assumed that parasites are severely limited in the hosts they affect and therefore, the spread of parasites to new hosts is limited. “If that was true, we wouldn’t see that many emerging diseases,” Brooks said. “But, in fact, we see a lot.”

Instead, Brooks notes that it’s important to examine changes in opportunity to switch to new hosts. “And this is where climate change, as well as anthropogenic activities, play a key role. We think that what happens is parasites evolve in a particular place geographically associated with particular hosts in that place,” Brooks said. “But, there are likely other hosts in other areas that are susceptible to the parasite, but have not been exposed.”

With climate change, species move around the planet, and parasites come in contact with these susceptible hosts. And since the new hosts have never been exposed to the parasite, there has never been a chance for them to evolve resistance, and disease results.

Brooks and his colleagues have conducted parasite inventory projects in tropical, temperate and boreal regions of the world. In each case, scientists discovered large numbers of previously undocumented parasite species, as well as many species that had previously been known from other geographic areas where they inhabited other host species. This global evidence of parasites shifting hosts made the scientists aware that that the potential for emerging disease was much greater than anticipated.

Their findings apply directly to wildlife in North America where there is particular evidence of climate change facilitating emerging diseases, Brooks said. Take the case of Heartworm, a disease in dogs caused by the parasitic worm Dirofilaria immitis and transmitted by mosquitos, which clogs the heart and major blood vessels leading from the heart.

“When I was a graduate student, we called D. immitis ‘dog heartworm’ and because of the temperature requirements of the mosquito vector, we assumed it would never move north of the Mason-Dixon Line,” he said. “By the time I arrived at the University of Toronto, veterinarians in Ontario were already dealing with the parasite.” In fact, by 1981, scientists had documented the parasite — once believed to be restricted to dogs — in wild canids and subsequently in mustelids, pinnipeds and even humans. “Clearly, the parasite always had the means of switching hosts, but only recently has been given increased opportunity.”

Brooks said many parasites are similarly expanding their geographic ranges as a result of climate change and anthropogenic activities. Wildlife and domestic animals are interacting on a regular basis exchanging pathogens that move back and forth between one another. For example, feral pigs interact with domestic pigs, and bison, deer and wild sheep interact with livestock.

Still, there are ways to combat this problem.

“The main thing is that first, we need to stop pretending we can stop climate change or reverse it,” Brooks said. “It’s happening and intensifying. We need to begin to anticipate what’s going to happen and think of ways to minimize the impact.”

Brooks said scientists must document, assess, monitor and act — a strategy commonly referred to as DAMA — when it comes to managing the spread of emerging diseases. He said biologists can minimize the impact of emerging diseases by anticipating what will happen and minimizing exposure to pathogens.

“The idea is to have as much information about where potential pathogens are (and how their geographic distributions are changing) and how they’re transmitted,” Brooks said. “All of the information gathered needs to be online and freely available to help lessen the impact of emerging diseases.”

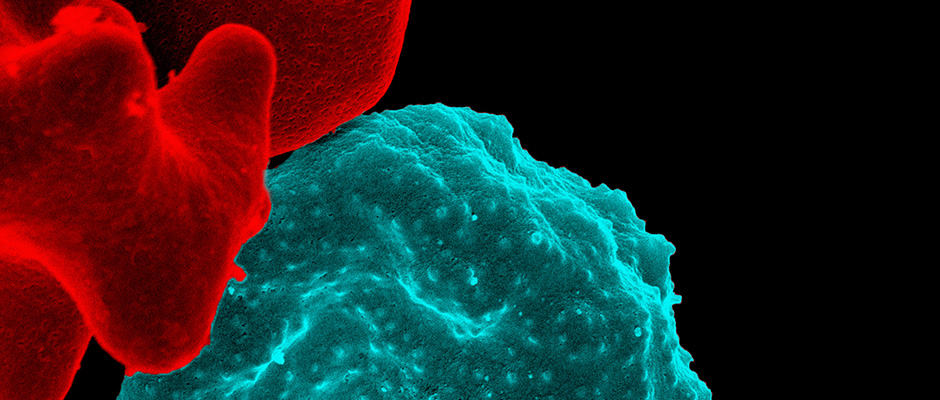

Header Image:

Scientists are studying malaria-infected blood cells, such as this, to better understand how malaria and other emerging diseases impact their hosts. Recent research shows that climate change could increase the spread of emerging disease around the world.

Image Credit: NIAID