Share this article

Supposed wolf species may actually be hybrids

American canids are all mixed up, genetically speaking. That’s the conclusion of a new study examining wolf and coyote DNA, and the findings could change which animals receive Endangered Species Act protection.

Red wolves (Canis rufus) have long been protected as a separate species, and more recently, researchers have proposed that “eastern wolves” in Canada’s Algonquin Provincial Park also represent a unique species. The new study released today is the first to examine the complete genomes of red and eastern wolves, and it suggests that both are actually recent hybrids of gray wolves (Canis lupus) and coyotes (Canis latrans).

“We asked, is there anything unique in the genome of eastern wolves or red wolves which is not found in our reference sets? And we couldn’t really find anything,” said Robert Wayne, senior author of the study that was published in Science Advances. “The genomic composition of eastern wolves and red wolves could be explained simply by hybridization between gray wolves and coyotes.”

The data suggests that red wolves emerged in the 1800s or somewhat earlier, when humans were exterminating gray wolves from the Southeast and converting forests to farmland. Gray wolves might prefer to mate with their own kind, but as wolf mating partners grew scarce, the survivors may have settled for coyotes. Eastern wolf ancestry appears even more recent, taking place within the last century as wolves declined and coyotes expanded in more northern regions.

Despite the similar history of red and eastern wolves, the conservation implications could not be more different. The revelations about red wolves could mean the end of a decades-long conservation effort, while the ones about eastern wolves could help gray wolves keep their endangered species status.

In an attempt to save red wolves, researchers in the 1970s trapped 17 animals they judged to be relatively pure examples of the species, and used 14 of them to start a captive breeding program. Now, red wolves have no self-sustaining populations in the wild, and the USFWS has been working to reintroduce them to their supposed native range. But all these efforts are based on the red wolf’s original listing under the ESA, which assumed that they were a separate species. If they aren’t, groups that oppose reintroductions could argue that the animals have no valid legal protection.

Meanwhile, the original ESA listing for gray wolves included the Algonquin State Park area in the gray wolf’s native range. But in the last few years, researchers have published controversial evidence that Algonquin wolves come from a unique genetic lineage, with ancestors that diverged from gray wolves and coyotes long ago. If these animals represent a separate species, it could mean that gray wolves were never native to that area at all, and part of the gray wolf ESA listing was based on a flawed premise.

In 2013, the USFWS responded to the eastern wolf research by proposing a rule change to revoke the original ESA listing for gray wolves, retaining protections only for one subspecies found in the Southwest. The plan met with opposition from wolf conservationists and some researchers, and the final outcome is still uncertain, says Wayne. The new study supports the original gray wolf listing, though it’s not yet clear what difference that will make.

“The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service takes into consideration the best available science to inform our policy and wildlife management decisions, including for reviewing species under the Endangered Species Act,” said Vanessa Kauffman, spokeswoman for the USFWS.

Not everyone is ready to abandon the idea of eastern wolves as a species. Linda Rutledge, an evolutionary ecologist at Princeton University who has studied eastern wolf genetics, doubts whether the two Algonquin wolf specimens used in the study really represent the population. Moreover, she says, some of the analyses lumped the Algonquin wolves together with wolves from the Great Lakes, which are not considered eastern wolves.

“They have two samples from Algonquin that were collected during the 80s and 90s, a time of heavy hybridization with coyotes. They could be anything,” she said. “It doesn’t actually say anything about eastern wolves.”

But Wayne points out that even if the Algonquin wolves in his study had recently bred with coyotes, a full-genome analysis would reveal each species present in their ancestry. If one of the animals had a great-great-great-grandparent that was neither neither gray wolf nor coyote, it should have shown up.

“The magic thing about genomes is that you kind of compensate for the lack of geographic sampling with the number of base pairs that you examine — 2.1 billion,” he said. “That complete genome sequence provides in miniature an entire history of the species.”

While Wayne and Rutledge may disagree about the genetic details, they are united about what it should mean for wolf conservation. Policies that are based on protecting “pure” species are outdated, say the researchers, not reflecting the true complexity of ecosystems and populations.

The ESA itself is broad and flexible, capable of protecting any unique population of animals, says Wayne. But currently, there is no policy in place for dealing with hybrids. That could be bad news for red and eastern wolves, which both represent unique populations and valuable genetic diversity.

“Whatever you’re going to call it, a species or whatever it is, they clearly have something different about them,” says Rutledge. “And that should be enough to say, ‘this is worth conserving.’”

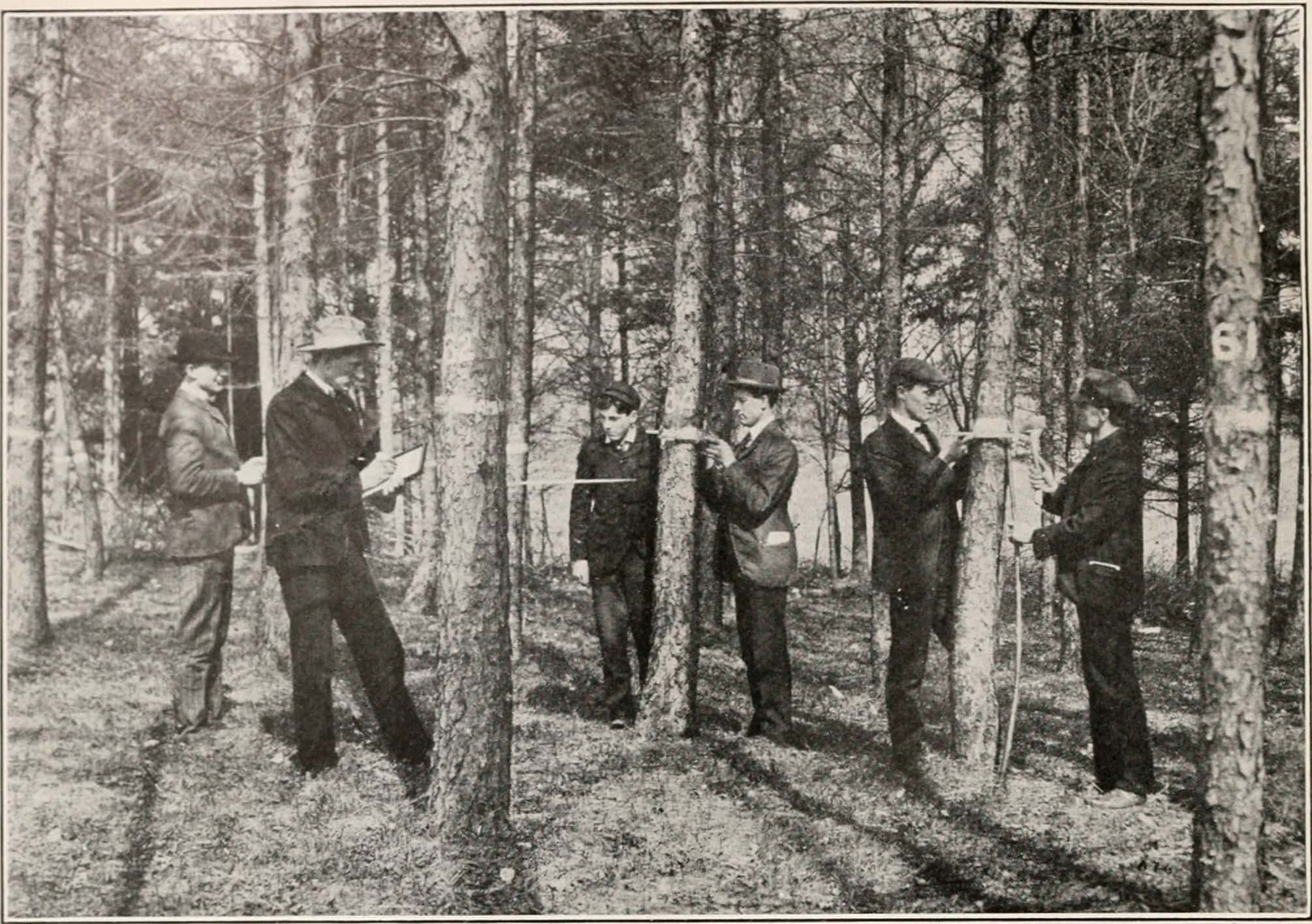

Header Image: These offspring of a male wolf and a female coyote helped demonstrate that wolves and coyotes can hybridize. Now, new research suggests that red wolves and eastern wolves are actually wolf-coyote hybrids. ©