Share this article

PFAS connected to alligator immune issues

When high levels of so-called “forever chemicals” appeared in drinking water coming from the Cape Fear River in North Carolina, researchers turned to alligators to see just how high the levels were and what that might mean—for alligators and for humans. They found the chemicals correlated with immune issues experienced by the reptiles, whose long lifespans could have subjected them to prolonged exposure to various chemicals over the years.

“We wanted to use alligators as a sentinel species,” said Scott Belcher, an associate professor of biological sciences at North Carolina State University. “People come and go, and there’s changes in drinking water. We asked ourselves if we could use alligators as these sentinels since they’re long-lived.”

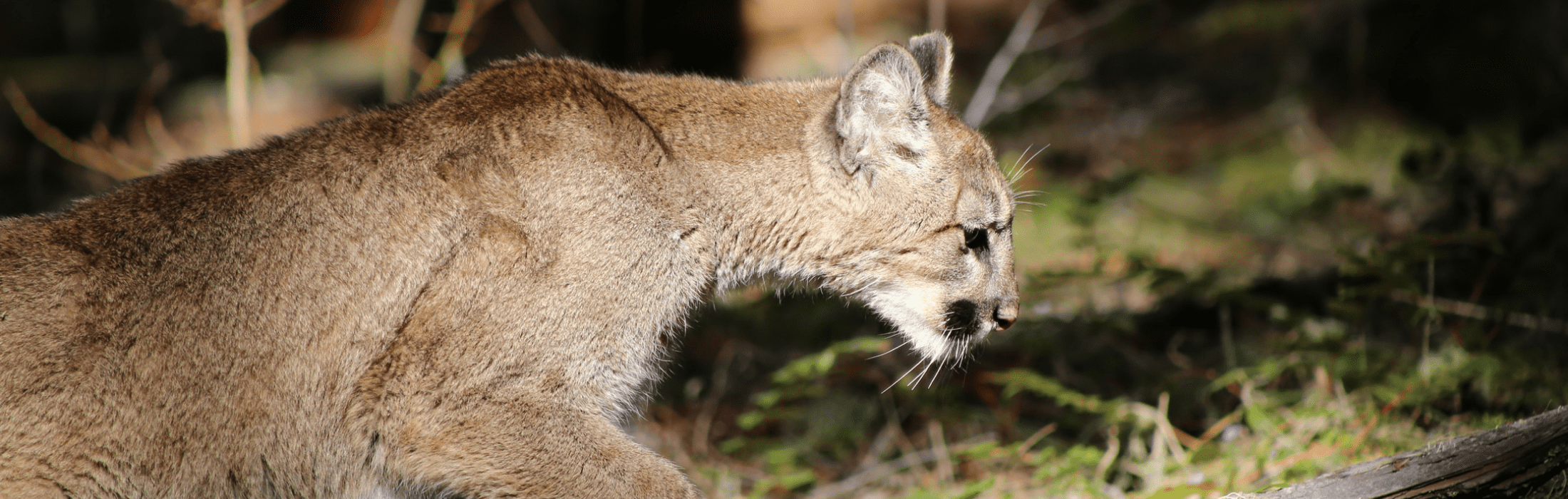

Scott Belcher, Matt Guillette and Theresa Guillette (left to right) hold an alligator with its snout secured with duct tape. Credit: Theresa Guillette

Belcher led a study published in Frontiers in Toxicology comparing alligators (Alligator mississippiensis) in Cape Fear to those nearby in Lake Waccamaw, which had much lower levels of these PFAS chemicals.

PFAS chemicals have been used for decades in household and industrial products. Many have been banned due to their connection with health issues in humans and wildlife, but they can linger in the environment. Meanwhile, new versions of the PFAS chemicals are being created, often chemically similar to banned substances.

Scott Belcher holds a baby alligator. Credit: Theresa Gullette

Getting ahold of the alligators was not an easy feat. After catching them with a heavy-duty rod and reel, teams of four to six people duct taped the alligators’ jaws closed, grabbed a blood sample, took measurements, removed the tape and released them. They did that 350 times, taking the samples back to the lab to analyze them for PFAS.

While conducting their fieldwork, the researchers noticed many of the Cape Fear alligators had strange wounds that weren’t healing. “Some of them were clearly covered with fungus and were infected with other bacteria,” Belcher said. “That’s not usually observed in alligators. They usually have plenty of wounds from mating or other interactions, but they usually heal pretty quickly.”

That observation led the team to use the blood work to assess the alligators’ immune functions. “This was the kind of story of keeping our eyes open and following what our observations were telling us,” he said.

In the alligators from Cape Fear, where PFAS concentrations were higher, they found a gene related to immune response at levels 400 times higher than those in Lake Waccamaw alligators. “We cannot say that PFAS are causing this, although we do have some fairly strong correlations,” Belcher said.

But moreover, he said, the study shows the importance and breadth of the One Health approach, a holistic approach that considers the health of humans, wildlife and the environment. That approach is often used in managing disease threats that can affect wildlife and humans. But it can also be applied to chemicals in the environment, Belcher said.

Header Image: ©Lindsay Somers