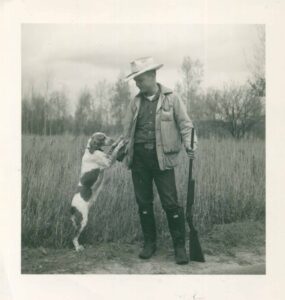

Dr. Lytle H. Blankenship spent the majority of his childhood running around barefoot on his family’s 72-acre farm in South Texas. Growing up in the throes of the Great Depression, shoes were a commodity the 14 Blankenship children went mostly without. Heavy, well-worn quilts, fashioned by his mother, were laid on the drafty floor boards of their one-room shack to serve as makeshift beds. During the day, the quilts were rolled up to create extra space and placed in an empty corner or on the one bed, used by his parents.

The humble conditions from which he came remained with Blankenship throughout his life and carried into his wildlife career. But the contributions he has made over the decades have been significant and relevant to wildlifers around the country — and the world. For TWS members and current wildlife professionals, Blankenship’s story is sure to be relatable, and hopefully inspiring. That’s why his latest gift — just as much to his family as it is to himself and the wildlife profession — is the autobiography he recently published, titled “Trails That Lead Somewhere.”

“I decided I was not going to leave my family without some type of a history, and that’s one reason why I wrote my book,” Blankenship said, regretfully admitting that no one had ever taken down his parents’ history despite his mother’s brilliant memory. “Second… I wanted young people to know that you can make it on your own… I made it through three universities and to the pinnacle of my profession. And most people can do that, or more than they think they can do.”

Chronicling his life from the very beginning, the book uses Blankenship’s stimulating exploits — foreign and domestic — to portray themes of personal gratification, professional attainment, religious fulfillment and more, and forces readers to reflect on their own accomplishments.

An important chapter of his life, and one that the book focuses heavily on, is the three years he spent studying wildlife in east Africa. Blankenship was first approached by Dr. Jim Teer from the Department of Wildlife Sciences at Texas A&M University asking if he knew of anyone who would be interested in studying game cropping in Kenya. “Without much of a thought I said ‘yes, I would.’ Well, he didn’t think I’d be wanting to go over there with my wife and four children, but I convinced him that I would, and I did this without even asking my wife.”

After retroactively asking his wife’s permission, Blankenship packed up his family and flew them across one ocean and nearly two entire continents. The intended area of study — game cropping for the purpose of providing meat protein to natives — didn’t pan out, so instead he studied the compatibility of wildlife and livestock on European ranches with Dr. Chris Fields of Wales. He later received the Chevron award for the work he had done in Africa and maintains that the three years he spent there with his family was the best opportunity of his life.

Sometime later, after returning to the United States, Blankenship was elected as president of TWS. His presidency fell during a brief period in the Society’s history when that position was held for two years instead of one. He made a point of visiting every section during those two years, and when they were over, Blankenship retired from Texas A&M Agricultural Experiment Station as professor emeritus. Though he never got tired of doing research, he did get tired of sitting at a desk and decided he didn’t have to do that anymore. He remained active in TWS, however, and looking back at his retirement, he says his most significant contributions since then were his role in the inception of a yearly, independent TWS meeting, now known as the Annual Conference, and chairing the Aldo Leopold Award Committee. He is an Honorary Life Member and Fellow of TWS, as well as a charter member of The 1,000, donating $1,000 to the initiative last year.

Sometime later, after returning to the United States, Blankenship was elected as president of TWS. His presidency fell during a brief period in the Society’s history when that position was held for two years instead of one. He made a point of visiting every section during those two years, and when they were over, Blankenship retired from Texas A&M Agricultural Experiment Station as professor emeritus. Though he never got tired of doing research, he did get tired of sitting at a desk and decided he didn’t have to do that anymore. He remained active in TWS, however, and looking back at his retirement, he says his most significant contributions since then were his role in the inception of a yearly, independent TWS meeting, now known as the Annual Conference, and chairing the Aldo Leopold Award Committee. He is an Honorary Life Member and Fellow of TWS, as well as a charter member of The 1,000, donating $1,000 to the initiative last year.

A photo of Blankenship can still be found on the composite of past presidents hanging in the conference room at TWS’ national headquarters in Bethesda, Maryland. Browsing through the names and photos of these leaders, you’ll find him positioned in the spot reserved for the 1986-1988 presidential term, wearing a pin on the lapel of his gray suit with the logo of the Society that has meant so much to him since joining in 1952. He encourages all young wildlifers to join TWS and become Certified Wildlife Biologists.

“Being a member of The Wildlife Society helped me to realize more the importance of our Society; importance of helping us to help other people understand wildlife,” Blankenship said. “As I have often said, don’t dream dreams, but dream big dreams; I did and it has been a blessing.”

You can purchase Dr. Lytle Blankenship’s autobiography, “Trails That Lead Somewhere,” by clicking here.

You can purchase Dr. Lytle Blankenship’s autobiography, “Trails That Lead Somewhere,” by clicking here.

Article by Nick Wesdock