At night, in the dark forest of New Zealand’s mainland Bushy Park reserve, you might look up and see a splash of bright yellow in the trees.

Pay close attention and you might even hear a “stitch, stitch, stitch.”

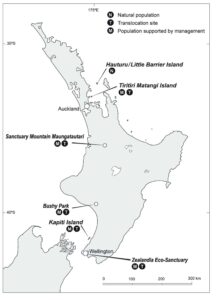

That is the call of the female hihi bird (Notiomystis cincta) — pronounced “heehee” — and, until recently, these sounds and sightings in Bushy Park would have been unlikely. In fact, 30 years ago, the rare hihi — also known as the stitchbird — was only found on Little Barrier Island — an over 10 square mile island in New Zealand’s North Island. Disease, habitat destruction and introduced predators such as rats had wiped out the birds from other areas of the country.

©Julia Panfylova

There have been several attempts since the 1980s to restore populations from Little Barrier Island to Hen Island, Kapiti Island and other areas of the country. However, issues such as the presence of predators have caused these efforts to fail. Today, the birds can be found in the Bushy Park reserve where there was a recent reintroduction as well as other areas such as Tiritiri Island in the Hauraki Gulf of New Zealand.

In 2013, a team of researchers flew 21 female hihis and 23 males over from Little Barrier Island to the approximately 250 acre Bushy Park reserve in an effort to increase the species’ range and global population size. They fitted all but five of them with tail-mounted transmitters to determine the location and status of the individuals. The team recently published a study in the Journal of Wildlife Management that examined how the birds were faring since the reintroduction.

“Our research tried to understand if Bushy Park was a suitable place for hihi,” said lead author Julia Panfylova, who, at the time, was a student at Massey University in New Zealand. Panfylova is now the project coordinator at Palmerston North City Environmental Trust, where she serves on the forest and bird committee. Panfylova added that the birds can’t just be left alone after reintroduction. “They need human intervention and constant monitoring,” she said.

As part of the reintroduction effort, Panfylova along with the Bushy Park team installed five sugar water feeders. They found, however, that the birds didn’t consume the sugar water as much as they expected and instead fed on fruit and nectar in the park. The researchers also set up additional nest boxes to accommodate for a potential shortage of mature trees in which the birds could nest. Further, the birds were in a predator exclusion area and, as a result, safe from rats — the species’ biggest threat.

Still, in the first breeding season, only four of the 21 females survived while most of the males survived. “We discovered females were more vulnerable to stress,” Panfylova said. Those four birds, however, were able to increase the population to about 50 birds, she says.

Panfylova explained that the acclimation period was about six months for them, meaning it took the population about that long to stabilize and prosper. “This acclimation period is different for different species and reserves, and sometimes different for males and females,” she said.

According to Panfylova, this study shows the importance of using structured decision making when considering reintroductions of species — a process that involves collaborating with stakeholders to weigh numerous factors . For example, at one point the researchers considered making a second translocation of the hihi bird from another island, but ultimately decided it wasn’t necessary since the population is growing.

However, she says it is likely there will be another reintroduction in the future in order to add genetic variation into the population. But Panfylova is hopeful about the future of the hihi population in Bushy Park.

“Maybe, in the future, we can just leave this population on their own and remove the feeders,” she said. “And maybe they will survive in Bushy Park on natural resources for food. This could happen.”

Article by Dana Kobilinsky