Predators and livestock can be a controversial combination anywhere, But it can be particularly contentious in South Africa, where livestock farmers complain about mounting impacts from carnivores on their operations.

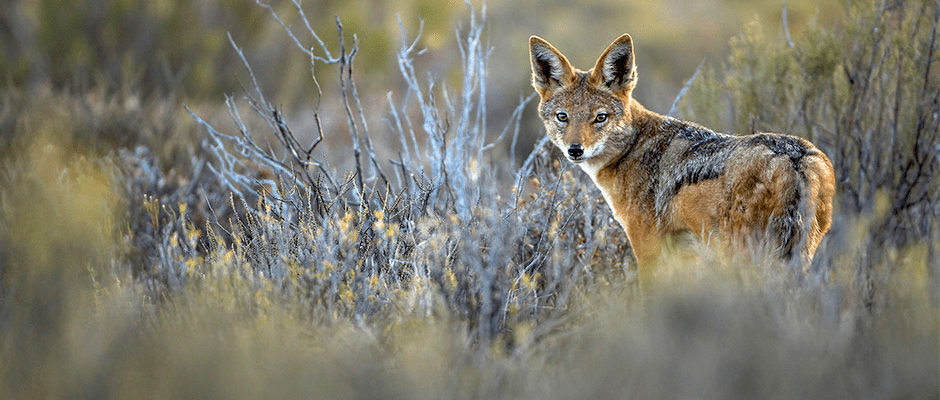

A new study available on early view in the Journal of Wildlife Management finds that livestock farmers in the semi-arid Karoo region have reason for concern. Looking at black-backed jackals (Canis mesomelas), researchers found the predator preferred to eat livestock even when similar-sized wild prey was available.

“Jackals showed a very large preference for livestock when they live on farmland,” said lead author and PhD candidate Marine Drouilly, of the Institute for Communities and Wildlife in Africa at the University of Cape Town, South Africa. ”They’re going to eat more sheep or more goats than would be expected given their availability in the landscape.”

Similar to coyotes (Canis latrans) or dingoes (Canis lupus dingo), jackals are opportunistic predators, eating whatever prey is available, including rodents and insects.

Farmers often complained that jackals would leave surrounding wild lands in search of livestock on the farms, then return to the reserves, Drouilly said. That appeared not to be true. In wild areas, the jackals appeared to subsist mostly on fruits, mice and other small mammals.

In farming areas, however, jackals did show a strong preference for sheep and goats, even when small antelope like the steenbok (Raphicerus campestris) were widely available.

“We can guess why jackals would prefer sheep – they’re not wary of predators,” Drouilly said. “They’re very white. You see them very well on the landscape. They don’t hide. They lost their anti-predator behavior. It’s a lot easier for a jackal to kill a sheep than a steenbok.”

The findings resonate anywhere farmers grapple with livestock losses from predators, Drouilly said, but in South Africa, struggling farmers have found it particularly difficult to deal with growing threats from predators. The problem is increasing, Drouilly said, as employment is falling on farms and more and more farms are bought as vacation homes, allowing the landscape to become wilder and support more predators. In addition, farmers receive no help from the government to protect their sheep or to compensate the predation losses.

“I’m hoping that this paper can be read by many people, especially from the government and NGOs, and they can look into helping farmers a little bit more with non-lethal tools against predation,” she said. “We don’t want to reach the point where famers, out of desperation, extensively use poison or other methods that are detrimental for wildlife.”

TWS members can log into Your Membership to read this paper in the Journal of Wildlife Management. Go to Publications and then Journal of Wildlife Management.

Article by David Frey