The effects of bright cities on migratory birds isn’t something to take lightly, but the biggest cities may not have the biggest impact on long-term journeys.

Instead, cities that lie directly on the common routes those birds take may be the biggest offenders, according to new research.

As a result, cities like Chicago, Houston and Dallas likely have a bigger effect on birds than bigger and brighter urban areas like New York City.

“We wanted to catalog the risk here,” said Kyle Horton, a post-doctoral researcher at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and the lead author in a study published recently in Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment.

City lights can often be fatal to migratory birds as they attract them and lead to collisions with tall buildings. One study published in 2014 found that as many as 988 million birds were killed this way every year in the United States. In other cases, they might lead the birds astray from their habitual migration, causing a loss of critical energy needed to sustain them on their long journeys.

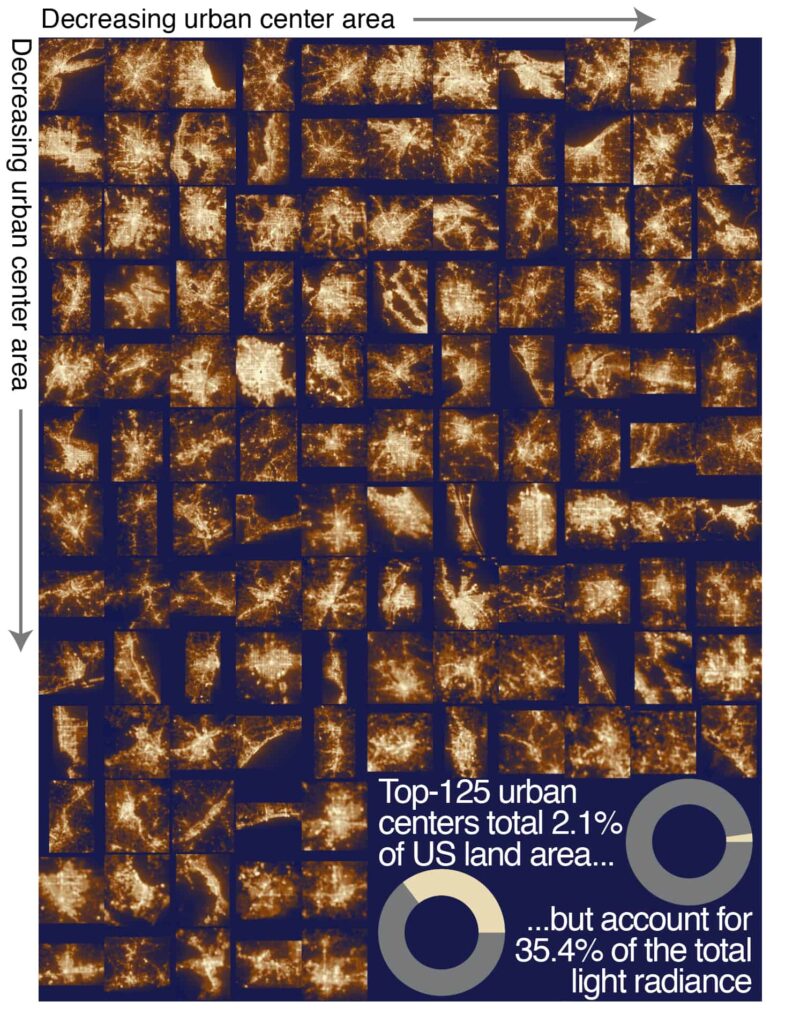

Horton and his co-authors combined radar information that tracked bird migrations with satellite images of 125 of the largest cities in the U.S. The data sets allowed them to combine information about the size of the urban area and the brightness of the cities with common migratory bird routes.

They discovered that the city with the biggest impact was Chicago, followed by Houston and Dallas, because migratory birds often pass over these cities during both their spring and fall migrations.

Other large cities like Boston showed a relatively low risk for its size for migratory birds. While it’s the fourth largest U.S. city by area size, Boston is the 24thriskiest city for migratory birds in the fall and 36thin the spring, likely due to the fact that there isn’t much land mass directly south or north of the coastal city.

They also found that some cities showed important variation depending on the time of year.

West Coast cities tended to rank higher for exposure during spring migration when birds were heading northward, with Los Angeles sitting at fourth overall in terms of the light pollution dangers it poses to migratory birds.

But Los Angeles drops to number 37 during the fall migration, when many migratory bird species travel using inland aerial pathways at higher altitudes rather than coastal routes.

“If we look at the top 10 cities which show the greatest change between spring and fall migrations, they all sit on the West Coast,” Horton said.

The East Coast showed the opposite effect, with migratory birds seeing more exposure to bright city lights in the fall as opposed to the spring, he said, since birds often go up through the central flyway during the latter period.

This could be especially problematic since birds flying southward in the fall more often include younger birds that are making their first long-distance flight. Horton worries these inexperienced birds may be more vulnerable to the problems posed by night lights in cities during this period.

Cities like New York are already taking some measuresto reduce the risk to migratory birds by turning out lights.

Horton said that it would be ideal for cities to keep their lights out more often all the time, but the risk to migratory birds could be significantly reduced by having cities that lie in migratory corridors to turn out the lights in tall buildings for a few weeks during critical migratory periods.

“The ultimate thing that we’d love to see is that lights are turned out in a more blanket situation,” he said. If this is unfeasible, he urges city managers to use the ornithology lab’s BirdCast website, which gives one-, two-, and three-day forecasts for bird migration in regions across the U.S. to give a better day-by-day assessment of the best times to keep the lights down low.

“Most migrations happen during about seven nights during spring and fall,” he said.

Horton said other factors may also be at play in cities, such as the structural characteristics of their skyline. Birds might be easier led astray by lights in tall skyscrapers than in two-story houses. Further research would have to be conducted to determine how these factors might affect migratory birds, he said.

Article by Joshua Rapp Learn