Researchers often think about wildlife moving to other areas. Sometimes, biologists do it themselves, carrying out translocations to benefit populations. Other times, species follow optimal habitat as climate and human development change ecosystems. Sometimes, migrating is part of a species’ natural history. And sometimes, they hitch a ride on a hurricane.

It’s a phenomenon that’s been known for a while, said Matthew Van Den Broeke, an associate professor of meteorology at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

“People published observations from the 1880s of exhausted birds in the eye of a hurricane and landing on a ship,” Van Den Broeke said. “From people watching birds recreationally, it’s been known that after a hurricane, oceanic species have shown up inland.”

But Van Den Broeke found it isn’t as simple as flying species hopping in for an easy ride. Hurricane-driven winds and thunderstorms resulted in more birds and insects staying inside the eye of the hurricane and being moved with it, he recently discovered. The finding helps shed light on how species end up in areas they’re not used to, and how some may even become invasive.

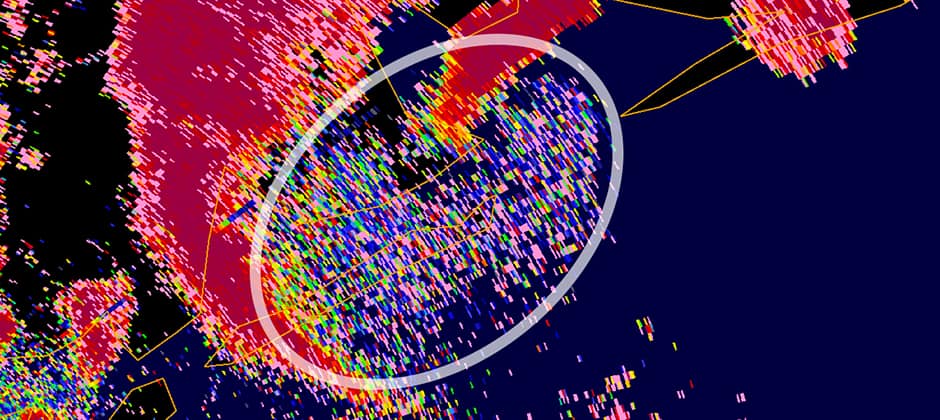

Researchers wouldn’t have been able to uncover the mechanisms behind these moves if not for a new dual-polarimetric radar capability. Under previous radar systems, it was difficult to distinguish a flock of birds from a rainstorm. But dual-polarimetric radar allows researchers to parse out non-meteorological occurrences—like wildlife, or, what meteorologists call bioscatter.

Van Den Broeke authored a study published in Remote Sensing in Ecology and Conservation looking at bioscatter on radar for 33 Atlantic tropical cyclones that struck the U.S. or Puerto Rico between 2011 and 2020. Every single storm had bioscatter associated with it. When he delved deeper, though, he found that each storm had a different bioscatter signature.

“Looking at those big hurricanes was neat,” he said. “But it was even more neat to look at the radar data and see the center was often full of birds being transported by the hurricane.”

Van Den Broeke found that more intense tropical cyclones, with higher winds and a more complete central ring of thunderstorms, tended to transport more birds and insects. In the eyes of these intense storms, birds flew at higher altitudes and in higher numbers to avoid the intense winds. “If I was a bird, I also wouldn’t want to fly through 100-knot winds,” he said.

He also looked at the eyes of these hurricanes to see how open they were—more closed eyes correlated with more thunderstorms. Those hurricanes also correlated with more birds being moved.

Van Den Broeke also found that timing was important. September and October had more bioscatter on the radar than May and June, he said. “We speculate that seems to be because we have more land birds migrating later in the season that have more opportunities to be incorporated into this circulation,” he said. There were also more birds being transported by hurricanes near the Gulf Coast and Florida.

This phenomenon can have ecological implications, particularly if climate change brings more and stronger hurricanes.

In terms of moving species, there may also be implications. “It’s pretty common to get reports of species that don’t normally occur in a place after the center of circulation has traveled over land,” he said. It’s also possible hurricanes can bring in invasive insects.

The study also poses some questions that can have meteorological implications, he said, helping him to look more at the structure of hurricanes. The reason that birds fly higher with more hurricane intensity may have to do with something called the inversion—the boundary between moist air rising from the ocean surface and drier sinking air above. “The height of inversion changes when the hurricane is strengthening or weakening,” he said. “Looking at the interface between the two layers, we might be able to monitor changes in the hurricane intensity remotely by looking at biological signatures.”

Meanwhile, Van Den Broeke is excited that he was able to combine two fields of interest. “I’ve always been interested in ecology,” he said. “I considered going to college for ecology but decided on meteorology instead, but I carried those interests along.”

Article by Dana Kobilinsky