Researchers believe an avian flu outbreak that has killed poultry and wild birds around the world may be responsible for a 2022 New England seal die-off. It is the first time the flu variant has been associated with a population-level impact among mammals.

In a study published in Emerging Infectious Diseases, researchers reported finding the H5N1 virus in dead harbor seals (Phoca vitulina) and gray seals (Halichoerus grypus) stranded along the Maine coast.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration declared the die-off an unusual mortality event in June 2022 after 64 harbor seals and 11 gray seals were found stranded in Maine. The event followed a pair of highly pathogenic avian influenza outbreaks among wild birds in New England, including gulls, eiders and other seabirds.

Researchers found no indication of the virus among seals after the first regional outbreak in birds, but in June and July, swab samples from stranded seals tested positive for H5N1.

Since it emerged in October 2020, the H5N1 virus has been responsible for over 70 million poultry deaths and affected multiple species of wild birds around the world. It has also resulted in over 100 infections of wild mesocarnivores, including foxes and skunks, primarily as a result of them eating infected prey. Scientists have found no conclusive evidence that the virus can be transmitted between mammals.

The link to seals wasn’t a surprise. Researchers have been tracking avian flu among seals for over 10 years, said Wendy Puryear, a scientist with Tufts University and a lead author on the study. Avian flu was suspected in an unusual mortality event involving seals in the Gulf of Maine in 2011, prompting researchers to continue conducting surveillance among marine mammals reported to NOAA’s Greater Atlantic Region Marine Mammal Stranding Network.

Since then, less serious virus occurrences have taken place among the seals. “We always pick up low pathogen influenza outside of any outbreaks we know,” Puryear said.

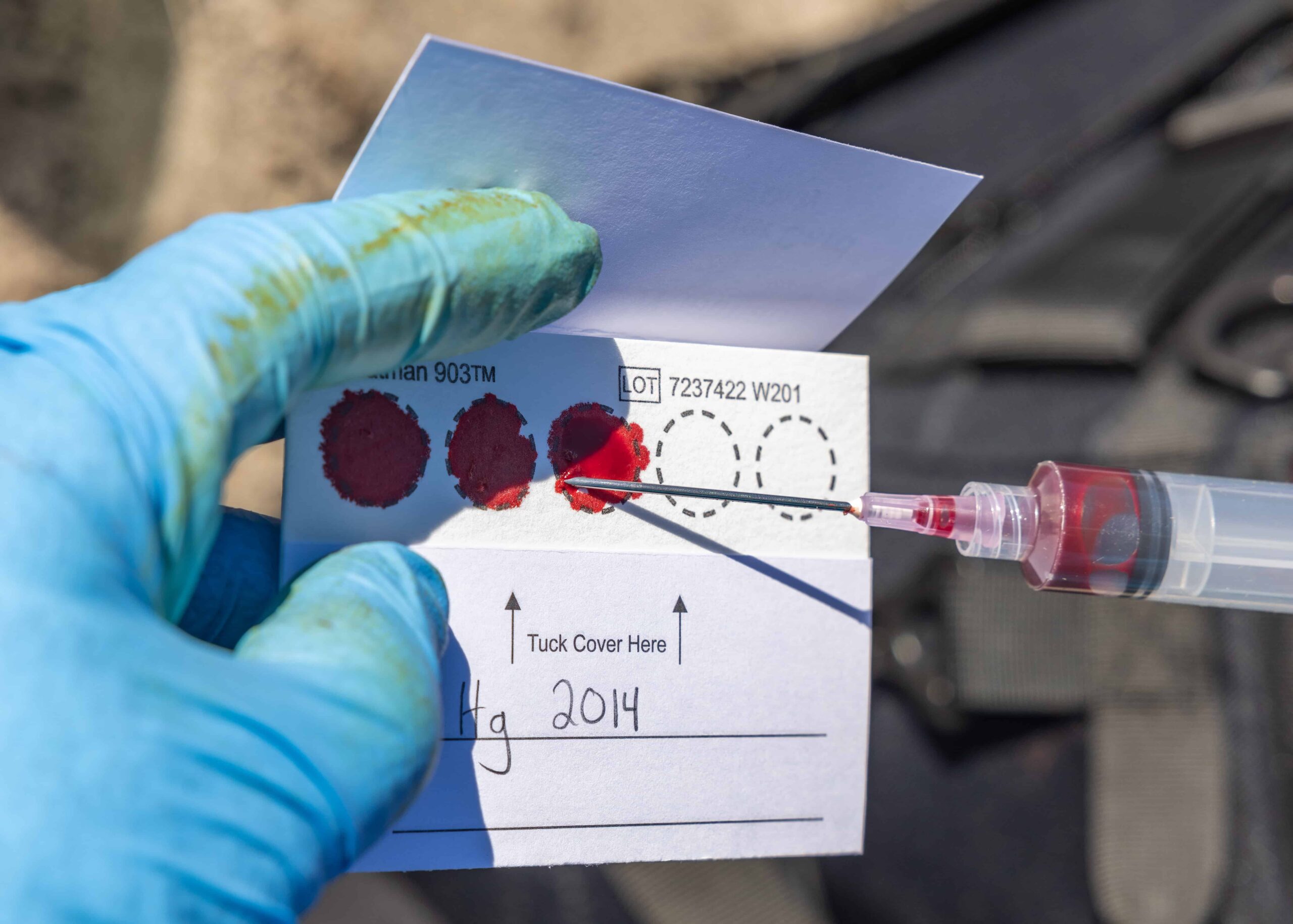

During last year’s die-off, Puryear and her team collected swab samples from stranded seals, including nasal swabs—similar to the way people are tested for COVID-19—as well as rectal swabs and swabs of the tear duct area, and they tested them for the virus.

They found that of the samples they tested, they detected H5N1 in 17 of 35 harbor seals and two of six gray seals, inferring that the mortality event is likely related to the outbreak.

Avian influenza can easily spread, due in part to poultry kept in cramped spaces and a lack of biosecurity measures to keep out wild birds, Puryear said, and climate change is likely to bring more species into contact with one another that otherwise wouldn’t have overlapped.

“You can’t vaccinate all of the wildlife around the world against H5NI,” Puryear said, “but this is a wakeup call that we’re impacting the bigger system.”

Article by Dana Kobilinsky