Share this article

As climate warms, polar bears take advantage of eider eggs

Polar bears (Ursus maritimus) in the Canadian arctic are taking advantage of a unique food source — common eider (Somateria mollissima) eggs — according to new research.

In a study published in Biological Conservation, researchers looked at the effects of a warming climate and melting sea ice in the Canadian arctic on common eiders, the largest duck in the Northern Hemisphere.

“Common eiders are a really cool species,” said Cody Dey, a Liber Ero postdoctoral fellow at the University of Windsor and the lead author of the study. “They are really important to local people in the Canadian arctic who hunt them for meat. They also collect their down from their nests. It’s the warmest down in the world, and they line their nest with it to keep their eggs warm.”

With one goal of the study to keep the sustainable activity going of collecting the down, Dey and his colleagues wanted to know how the ducks were faring in the presence of a changing climate, so they tapped into a current long-term data set on the eiders conducted by Environment Canada over the last 60 years.

They also flew up to northern communities in Canada and then took boats to visit eider colonies. “We would boat around and count eider nests,” he said. “And we would also keep track of whether polar bears have been there.”

Dey said polar bear droppings are a good indicator of their presence, but sometimes the researchers would actually spot polar bears preying on eider nests. Then, the team entered the data into a computer simulation model to predict what would happen to the eider population in the next 25 years if sea ice changes and polar bears prey on their eggs.

A male eider is all white while a female eider is brown. Melting sea ice provides an opportunity for female eiders to fatten up before breeding so that they can produce more eggs. ©David McGeachy

Dey and his colleagues found melting sea ice and earlier spring melt allows more access to underwater feeding grounds, so the eiders can prey on invertebrates such as muscles, starfish and even crabs. “With less sea ice, they are able to get access to food that they wouldn’t otherwise,” he said. “It’s important right before breeding.” As a result, female eiders were able to fatten up and lay more eggs.

However, they also found that less sea ice and more feeding eiders resulted in more polar bear predation of the species’ eggs. “Polar bears need sea ice to hunt seals,” Dey said. “They’re looking for other things to eat, and common eider eggs are available.”

While most people don’t think about polar bears feasting on eggs, Dey said, seabird researchers and Inuit people have noted them eating eider eggs since the early 1990s.

As a result of these two different effects of climate change, Dey and his colleagues found common eider population sizes would remain stable over the next 25 years, but rather than nesting in large colonies, the ducks will likely spread out into smaller colonies to avoid polar bear predation. Some evidence of that has already begun to appear, Dey said.

“Polar bears come to large colonies of eider nests to feed,” he said. “If it’s more dispersed, it’s harder for polar bears to find them and eat them.”

While these smaller colonies likely won’t have a negative impact on common eiders, Dey said it might affect people’s ability to harvest the ducks and to collect their down.

“We are quite worried about this for our Inuit partners,” he said. “It’s a cultural activity, like the annual fishing trip you do with your family. If there are only a few fish, you might stop going. It can weaken the connection with people and the natural landscape they live in.”

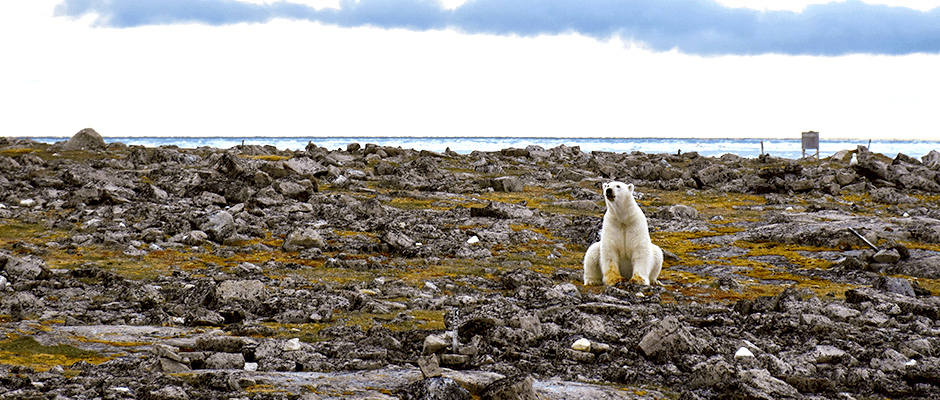

Header Image: A polar bear in the Canadian arctic has common eider egg yolk on its paws from eating the eggs. Researchers found while melting sea ice provides more food for the ducks, it also provides an opportunity for polar bears to prey on their eggs. ©Evan Richardso