Maintaining connectivity between habitats is a key strategy for conserving wildlife populations into the future. Yet here in the contiguous U.S., habitat fragmentation and loss threaten the well-being and even the survival of many wildlife communities. While habitat loss refers to the simple elimination of habitat, fragmentation occurs when habitat is divided into smaller, more isolated patches. Both are the result of land-use changes and human development, and both reduce the amount of suitable area available to wildlife species, separating wildlife populations in ways that may affect the population’s health and even its genetic viability, and interrupting migration routes.

Climate change is projected to exacerbate fragmentation by further disrupting landscapes. To make matters worse, it is also expected to shift the range of many species, forcing animal species capable of adapting by moving to expand into new areas to find more suitable temperatures and adequate food supplies – a challenge made difficult, if not impossible, by disconnected landscapes. A 2016 study shows that only 41% of current natural areas in the United States are connected enough to allow wildlife to move to more preferable temperatures.

Maintaining connectivity between habitats is a key strategy for conserving wildlife populations into the future. To help maintain, strengthen, and increase connectivity between landscapes, scientists across the country are actively working to ensure that managers and planners have sound scientific research upon which to base their decisions.

Serious Changes in the Southeast

Perhaps nowhere in the United States is habitat fragmentation more visible than in the Southeast, where rapid human development increasingly divides the remaining natural areas. In 2014, a Southeast Climate Science Center (SE CSC) study projected that urbanization in the region could increase by 101-192 percent over the next 50 years, creating a connected “megalopolis” from Raleigh to Atlanta.

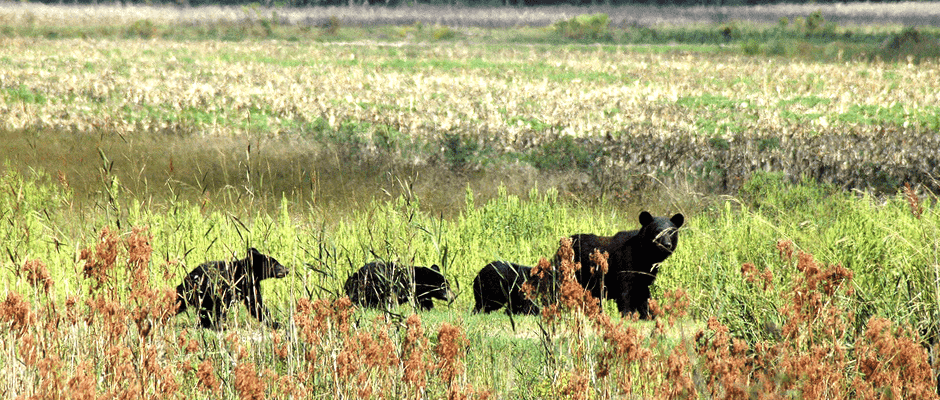

Scientists with the SE CSC, in partnership with the South Atlantic Landscape Conservation Cooperative, also recently assessed current and projected connectivity for three species that inhabit bottomland hardwood forests, a habitat of high conservation concern: American black bear, Rafinesque’s big-eared bat, and timber rattlesnake. Not surprisingly, the study results suggest that under anticipated climate conditions, there will be fewer connections for species to move between suitable habitats. This loss of connectivity adds to other threats facing this southeastern landscape, including sea level rise, urbanization, and land clearing and conversion.

Moreover, the findings also reveal that the connectedness of a future landscape will be species specific. For example, what may be sufficiently connected for a black bear to easily traverse long distances might well prove to be disconnected for a rattlesnake. This suggests a limited ability for managers to use the “umbrella species” concept to make generalized management decisions. The team additionally found that connectivity projections differ based on the model and method being used. Researchers suggest that managers and others use multiple techniques and focus on multiple species to get a more holistic, accurate representation of how species will use a particular landscape in the future and how connections between and among habitats can be strengthened most effectively.

Management Needs in the Northwest

Even in the more wide-open northwestern U.S., habitat fragmentation is a serious challenge to healthy and functioning ecosystems. Such is the case around the border of Washington and British Columbia, where research shows that increasing development and limited coordination of land and wildlife management threaten the movement of wildlife.

To support conservation decision-making in the region, Northwest Climate Science Center-funded researchers partnered with land and wildlife managers from both sides of the border, including Northwest tribes, U.S. state and federal agencies, and Canadian management agencies. Through a series of workshops, they assessed connectivity challenges for 13 priority species and ecosystems: American marten, black bear, Canada lynx, Lewis’s woodpecker, mountain goats, mule deer, tiger salamander, whitebark pine, white-tailed ptarmigan, wolverine, shrub-steppe habitats, and the Okanagan-Kettle region.

Scientists and managers used conceptual models to understand and project a wide range of future impacts to connectivity for the 13 case studies. Project participants also identified a diverse set of adaptation responses. For example, managers might implement prescribed burns, control invasive species, or restore riparian areas to maintain existing core habitat areas and their connections. Results from this project are available online and include key findings, data, and maps for each case study.

These projects are enhancing the ability of land and wildlife managers to collaboratively respond now to future threats to regional wildlife movement. The examples are only two of many projects supported by the Department of the Interior Climate Science Centers (CSCs) to provide natural and cultural resource managers with science and tools related to the impacts of climate change on fish and wildlife.

Management and national coordination for the CSCs is provided by the U.S. Geological Survey National Climate Change and Wildlife Science Center (NCCWSC). Have questions about our work? Contact us at nc****@**gs.gov. This story was written by Holly Padgett, Management and Program Analyst for NCCWSC, with input from the Southeast and Northwest CSCs.

USGS is a Leading Sponsor of TWS.

Article by The Wildlife Society