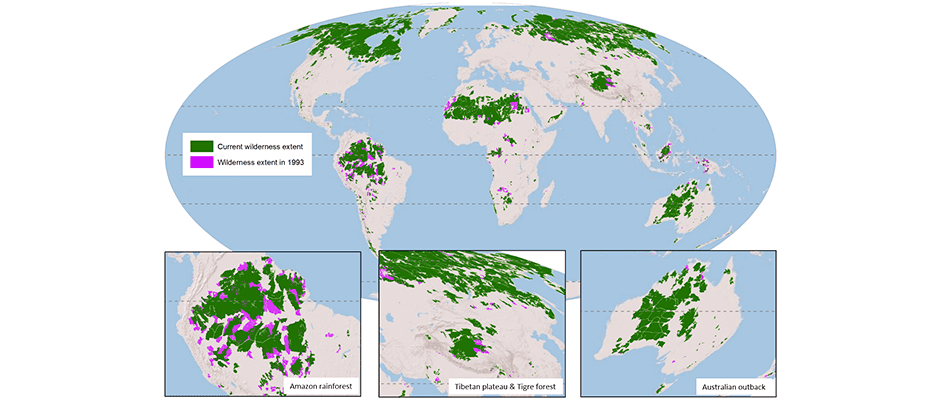

In the last two decades, 10 percent of the world’s wilderness has been lost, according to new research, from the boreal forests of North America to the rainforests of Papua New Guinea.

“Wilderness areas are such important places for biodiversity conservation, human livelihoods, and ecosystem services,” said James Allan, a PhD student at the University of Queensland School of Earth and Environmental Sciences and lead author of the study published in Nature. “They contain all the natural processes which support life on earth. It is impossible to overstate how important conserving them is.”

Among the areas most at risk are the Amazon, which lost a third of its wilderness, and the Congo rainforest, which lost 14 percent.

“This is particularly concerning since these tropical forests harbor a huge diversity of life,” Allan said.

Considering previous maps and assessments of wilderness conservation out of date, Allan and his colleagues undertook a massive project to map human pressure across the planet, and designating places free of human activity. They found these areas were retreating, primarily due to human population expansion, road and infrastructure expansion and agricultural expansion.

“We understood their importance,” Allan said, “and had a feeling that humans were starting to encroach into the wilderness areas, but we had no idea just how catastrophic the destruction was.”

Currently, wilderness areas have almost been completely overlooked in conservation policy, Allan said, and they receive very little funding. “This is because there has been a misconception that wilderness areas are safe because they are remote,” he said. “We show that this is not true, and that wilderness areas require immediate protection. They really are a global conservation priority.”

His team’s maps will be open to the public in the hopes that they can be used for wilderness conservation from the international level to the local level.

“Protecting the last wilderness areas really will be critical to stopping the current biodiversity extinction crisis,” he said.

Article by Dana Kobilinsky