Share this article

Invasive bermudagrass reduces habitat quality for bobwhites

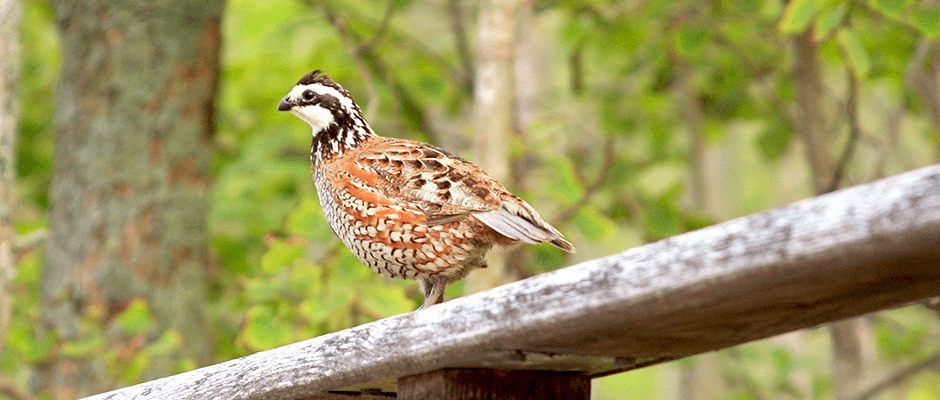

Anecdotal evidence of invasive bermudagrass (Cynodon dactylon) being associated with declining populations of northern bobwhites (Colinus virginianus) has been widely circulated.

But researchers at the University of Georgia wanted to test why the grass might be bad for the species.

“The two main research questions were how bermudagrass affects mobility — their ability to move around and forage—and how it might affect microclimate,” said James Martin, an assistant professor of wildlife ecology and management at the University of Georgia and member of The Wildlife Society. Martin, the lead author of the study published in the Wildlife Society Bulletin, worked with graduate student Jason Burkhart’s thesis data to test these hypotheses.

The researchers let five-day and 10-day old, human-imprinted chicks forage in simulated areas with different densities of bermudagrass. They found that bermudagrass reduced movement for five-day-old chicks, but not the 10-day- old cohort. “At 10 days, they were able to overcome this issue,” Martin said.

As for temperature, Martin and his coauthors compared average daily maximum temperature readings in areas dominated by bermudagrass and native forb-dominated areas. Using a published model that predicts how much thermal stress a bobwhite can take, Martin and his coauthors predicted how long a quail could survive under the different conditions based on their weight, a measure correlated with a bird’s age.

The team found that the birds did better in the forb environment. Based on their simulations, the chicks would reach thermal death much earlier in bermudagrass. “They were able to persist in the classical quail habitat much longer than bermudagrass,” he said.

Bermudagrass is grown as forage for cattle and horses. However, it often shows up in nonagricultural areas where it hasn’t been planted, making it difficult to for wildlife biologists to retain the habitat that certain species like bobwhites require. Martin says these areas are the ones where managers should focus on improving habitat and getting rid of bermudagrass. Doing so might also be helpful for other ground dwelling birds, he says.

However, getting rid of the grass may not be easy. Herbicides used on the bermudagrass are nonselective, meaning that while they kill bermudagrass, they kill all other vegetation along with it. Further, these herbicides have not been proven to be very effective, Martin says.

“Complete eradication in invaded areas is very tough,” Martin said. “It can be done, but it is not our expectation to eradicate [bermudagrass] in all areas.”

Header Image: ©Tim Lenz