Share this article

In the face of climate change some animals can adapt behavior

In the face of climate change, animals have a few options for how they can react — they can move to a new area, adapt, acclimate or die.

In a recent study published in Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, a team of researchers examined how species can acclimate by changing their behavior.

As part of a larger project looking at how species around the world cope with climate change, researchers completed a comprehensive literature review on invertebrates, amphibians, reptiles, mammals and fishes to help natural-resource managers allocate limited conservation dollars to species less able to adapt.

The team found behavioral responses to climate change were most commonly reported in species with a lifespan of at least three years and usually involved changes in the timing of life-cycle events such as reproduction or migration. Ecological generalists, such as raccoons and coyotes, were more likely to change their behavior than were specialists.

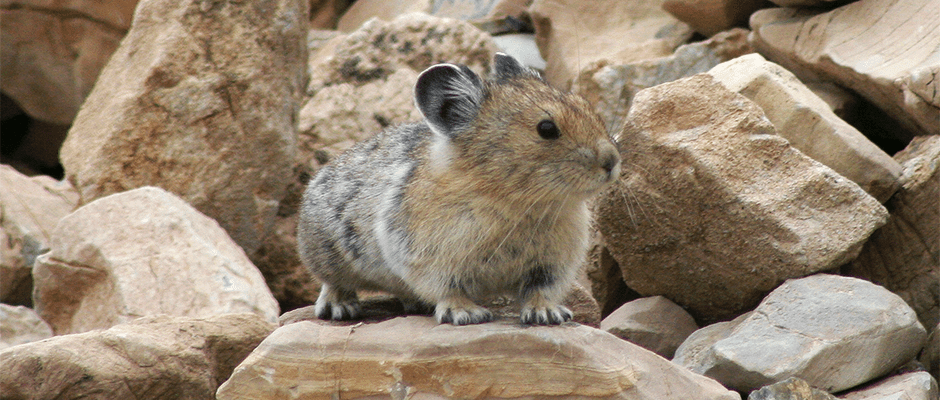

An exception to that was the American pika (Ochotona princeps), a species that TWS member Erik Beever, a research ecologist with the U.S. Geological Survey and lead author of the study, has been studying since 1994.

Pikas are easily detectable and are a good model for behavioral plasticity, Beever said. “They don’t move very far in any given day, week, or month. They’re likely to stay home, and they have very low dispersal rates generally, although we know that this varies across different landscapes.”

Far from being ecological generalists, Beever said, pikas are “specialists of cool and moist” conditions. Nonetheless, he identified behavioral changes they appear to be making to cope with a changing climate. They were moving off talus, the high-alpine boulder piles they are usually associated with, into the adjacent forest, he and his colleagues observed. Examining hundreds of pika photographs taken in Calgary, Beever noticed that during cooler months, the animals often balled themselves up to conserve body heat.

“Amidst a lot of discouraging stories, this is a little bit of a glimmer of hope for wildlife species in the face of climate change,” he said.

But these survival behaviors have consequences, too, Beever said.

“We recognize there are limits to this,” he said. “Behaviors require tradeoffs. Animals have these critical functions like obtaining food, obtaining water, and reproducing. Every time they’re dedicating energy to some different behavior, they can’t be doing these things.”

Header Image: An American pika stands on a rock in Glacier National Park in Montana. ©Glacier NPS