Share this article

For some species, muscle means water

For animals in dry climates, finding water is key to survival. One place that some species find it, a team of researchers found, is in their muscles.

“Most animals don’t have a moveable canteen,” said George Brusch IV, a doctoral student at Arizona State University and lead author on the paper in Proceedings of the Royal Society B. “The question is, if they’re not moving and they’re not drinking, how do they themselves survive? And what about their offspring?”

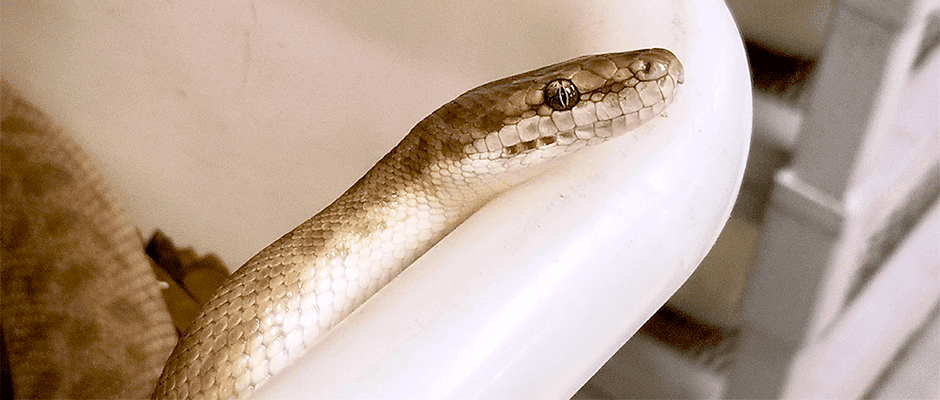

Brusch led a team of researchers from ASU and the Centre d’Etudes Biologiques de Chizé in France studying how capital breeders — species that use stored energy to fuel reproduction — might provide water for themselves and their offspring. Capital breeders include rattlesnakes close to home in Arizona, but Brusch’s team opted instead to study the Children’s python (Antaresia childreni) of Australia, which reproduces in the dry season when natural water resources are particularly scarce, consuming nothing during that time.

For capital breeders, Brusch knew, fat is important for converting to energy. But what about water? And what about muscle? While fat is only about 10 percent water, he said, muscle is 75 percent water.

During reproduction, his team found, muscle played an important role not only in providing energy but in producing water when it was otherwise unavailable.

Studying the snakes in a laboratory, the researchers compared reproductive and nonreproductive pythons. Half had no access to water during the three-week pregnancy, mimicking conditions in their native environment. The other half did.

At the end of the experiment, the researchers measured byproducts of burning fat and muscle, including ketones and uric acid, and they looked at muscle size and the snakes’ eggs. The pythons without water burned more muscle than fat to meet their water requirements, the team found, resulting in greater muscle mass loss. Their clutch sizes were similar to snakes with water, researchers found, but their eggs weighed less and the shells were thinner.

“There was a cost,” Brusch said. “They were able to burn muscle to survive and give a little water to their babies, but it wasn’t enough to offset the cost.”

None of the snakes, which are adapted to long periods without water, were clinically dehydrated, he said.

The results may have ramifications for other reptiles that, like Children’s pythons, are capital breeders, but Brusch wonders if the study may also apply to other taxa. What about hibernating bears? Or elephant seals, which don’t eat or drink while nursing their pups?

“I predict that a lot of animals that make uric acid will have this trend,” he said.

The activity may become more evident as climate change shifts rainfall patterns, he said. “This is a cool way animals may be, in the short term, be buffering themselves from potential changes in rainfall patterns,” he said. “They’re already adapted to living in these areas with prolonged periods without water.”

See the researchers at work in this video.

Header Image: Researchers at Arizona State University found Children’s pythons convert muscle to water for themselves and their offspring, but it comes at a cost. ©Sandra Leander/ASU