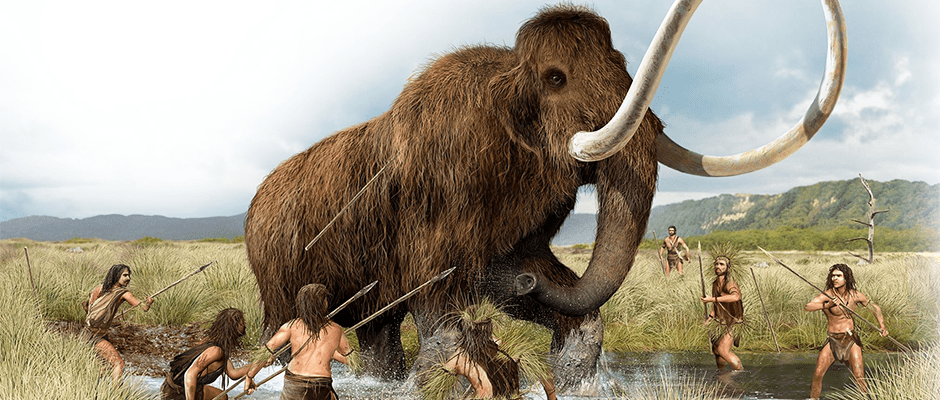

When humans reached North America 13,000 years ago, 78 species that weighed over a ton vanished in the terminal Pleistocene megafauna extinction. After scrutinizing the fossil record, a team of researchers recently concluded that these ancient humans and their forebears expanding over the globe obliterated big mammal species, much as human activity today is leading to extinctions.

“As humans migrated out of Africa, a wave of extinction of large-bodied mammals followed,” said Felisa Smith, lead author on the paper published in Science. “Modern extinctions are a continuation of this trend.”

A biology professor at the University of New Mexico, Smith and her colleagues studied mammals’ body sizes and extinction dates alongside primitive humans’ migration patterns and climate on every continent.

“We found size selectivity in extinction only when humans entered the picture,” Smith said. Researchers found no indication that climate change alone ever caused more frequent or size-biased extinctions.

“Our finding that 125,000 years ago, body size in Africa was much smaller than you would expect was surprising,” she said. “It suggests that early hominins had an impact on African ecosystems. By 1.6 million years ago, early hominins were eating meat and became better predators as we were evolving and immigrating. By the time Homo sapiens get into the Americas, they had sophisticated long-range hunting weapons, so extinctions became more rapid and more targeted towards larger-bodied mammals.”

The biologists also forecasted that land mammals would keep shrinking to the smallest they’ve been in 45 million years if all the imperiled ones suffered extinction over the next two centuries due to direct exploitation and habitat conversion.

“If it weren’t that we’ve urbanized so much of earth’s habitat, coping with anthropogenic climate change might not be such an issue, if animals still could move around as well as adapt in situ,” Smith said. “The long-term implications are the homogenization of ecosystems and loss of all large-bodied animals if we don’t become more proactive to conserve them. Large-bodied animals have a disproportionate influence on ecosystems through their foraging and ecological interactions. A lot of unforeseen consequences could occur if we lose all large-bodied species.”

Smith’s team is now investigating how the extinction of prehistoric megafauna affected other North American species.

“About 13,000 years ago, North America had a mammal megafauna community that was more diverse than in modern-day Africa — woolly mammoths, llamas, camels, ground sloths, short-faced bears, Smilodon, cave lions — but it was hammered by our ancestors’ effects,” she said. “The most important thing we can do is maintain habitat for large-bodied animals and maintain connectivity between habitats. If we do that, we can hopefully continue having these species in the future.”

Article by Julia John