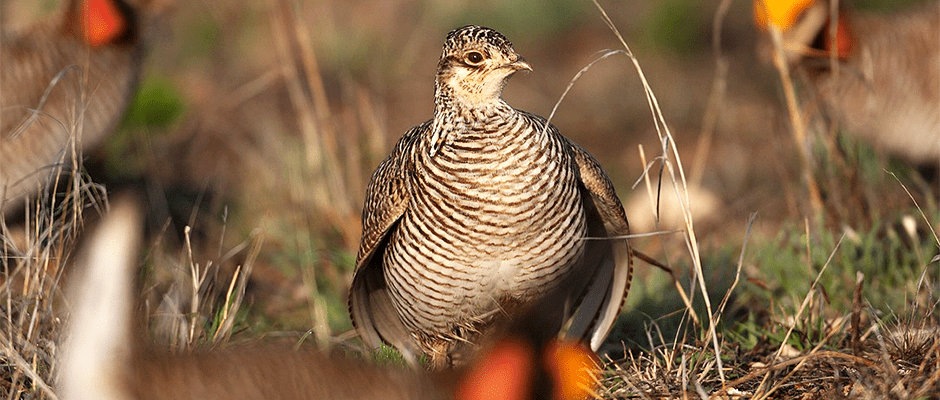

On the plains of western Kansas, Conservation Reserve Program lands, where crops have been replaced by native grasses, have proved crucial to lesser prairie-chickens (Tympanuchus pallidicinctus). The threatened birds have established themselves in a part of the state where they weren’t historically known — and one of the few places of the country where their numbers are increasing — using these grasslands set aside for environmental benefits.

But the birds mostly use CRP lands during nesting and the nonbreeding season, researchers found, suggesting that a mosaic of grasslands across a broader landscape is necessary for the birds’ success.

“If you establish a CRP field in the middle of a crop field landscape, that’s not really going to do very much for lesser prairie-chickens,” said TWS member Dan Sullins, a postdoctoral research associate with the Kansas Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit at Kansas State University and lead author of the paper in the Journal of Wildlife Management. “But if you establish a CRP field next to it a large remaining tract of native grasslands, it can really provide important habitat.”

The Conservation Reserve Program was created in 1985 by the U.S. Department of Agriculture to encourage farmers to avoid planting crops on sensitive lands and grow environmentally beneficial plants instead. In western Kansas, CRP lands tend to be planted with native tall-grass prairie species. These provide important cover for lesser prairie-chickens during nesting, Sullins said, but the grasses and thatch can be too thick for little chicks to walk through or for adult birds to keep a watch out for predators.

The Conservation Reserve Program was created in 1985 by the U.S. Department of Agriculture to encourage farmers to avoid planting crops on sensitive lands and grow environmentally beneficial plants instead. In western Kansas, CRP lands tend to be planted with native tall-grass prairie species. These provide important cover for lesser prairie-chickens during nesting, Sullins said, but the grasses and thatch can be too thick for little chicks to walk through or for adult birds to keep a watch out for predators.

So during brooding, he said, the birds typically uses native grasslands grazed by cattle. That has worked out well in western Kansas, Sullins said, because — sometimes by design and sometimes by happenstance — CRP lands often abut short-grass prairie. “It’s allowed those larger landscapes to provide for the full life cycle of lesser prairie-chickens,” he said.

Sullins and his team captured and fitted 280 female lesser prairie-chickens with transmitters during spring lekking seasons between 2013 and 2015 to monitor their habitat selection. They found nest densities were about three times greater in CRP grasslands than on surrounding ranchland.

“We were surprised to have that significant a result,” Sullins said.

That great nesting habitat did not turn out to be brooding habitat, however. Researchers found 85 percent of females with broods surviving to seven days moved their young other landscapes. These surrounding landscapes proved critical, they found. Prairie-chickens were eight times more likely to use CRP if the surrounding landscape was 70 percent grassland rather than 20 percent.

The study points to the importance of CRP for the birds in western Kansas, but also to its limitations, Sullins said.

“Providing for all the needs of lesser-prairie chickens with a 160-acre patch of CRP is just not going to happen,” Sullins said. “It’s not big enough. It doesn’t provide for all of their life stage needs.”

TWS members can log in to Your Membership to read this paper in the Journal of Wildlife Management. Go to Publications and then Journal of Wildlife Management.

Article by David Frey