The University of Alaska Museum (UAM) Mammal Collection houses the largest collection of marine mammal specimens in North America. Its holdings include specimens from more than 12,000 walrus, 15,000 seals, 1,100 sea lions, 3,200 sea otters, and 1,100 cetaceans (whales, porpoises, and dolphins). The collection contains specimens from every species found in Alaskan waters, however, most cetacean specimens consist of tissue samples only with very few skeletons available for research. The large size of most whales and porpoises coupled with the remote sites where they are typically found beachcast, make salvaging a whole carcass arduous at best.

On June 28, 2016, an adult male humpback whale washed up, freshly dead, near Hope, Alaska. A necropsy was performed, and tissue samples were collected by Dr. Pam Tuomi and biologists from the Alaska Sea Life Center and the National Marine Fisheries Service the following day. No cause of death has been determined. The carcass was set loose and the tide took it further up Cook Inlet just below the motocross area of Kincaid Park in Anchorage. We knew that there would likely never be a better opportunity to collect such a valuable specimen and since there was not yet a full skeleton of a humpback whale in our collection, we were determined to salvage this one. UAM was authorized by NMFS, as a member of Alaska’s Marine Mammal Stranding Network and under our marine mammal permit (#18727), to collect the whale skeleton.

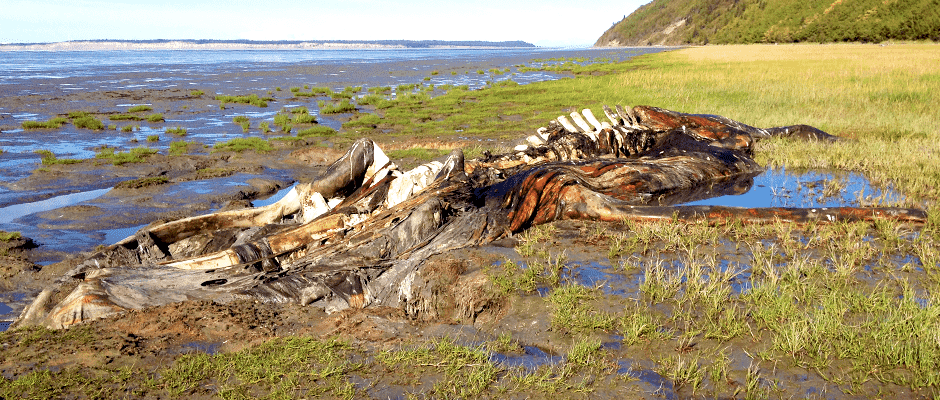

After two months of bird, maggot, and bacterial action, the skeleton began to emerge from the flesh. On September 8, four UAM staff (Aren Gunderson, Kevin May, Larry Pallozzi, and Kelly May) drove from Fairbanks to recover the bones that could be salvaged by hand and hauled up the steep bluff in frame packs. The carcass was steaming, and the stench was incredible though not unfamiliar to those of us experienced in marine mammal specimen preparation. Maggots were 6 inches deep in places and sounded similar to the fizz of a freshly opened soda can. The slight breeze was welcome and kept fresh air available on one side of the carcass.

With volunteer help from the Friends of the Anchorage Refuge (FAR; Barbara Carlson, Barbara Wild, and Saige Thomas) and the Alaska Department of Fish and Game (Josh Brekken), we made 40 round trips up and down the bluff, salvaging 39 vertebrae, three ribs, and part of one flipper. After one long day, what remained of the carcass was either too heavy to be hand carried or too inaccessible within the remaining soft tissue. We departed Kincaid Park that evening and began making plans to salvage the rest, which would require a helicopter to sling the remaining parts up the bluff.

On October 10th we returned to the site, this time with the same crew from UAM plus one more seasoned veteran of marine mammal salvage (Kyndall Hildebrandt). Alpine Air was contracted to do the slinging via helicopter. With help again from FAR as well as Alaska Veterinary and Pathology Services (Kathy Burek, Serena Jordan), we spent one more day on the carcass, gathering all the remaining postcranial bones (ribs, tail vertebrae, flippers) into a cargo net. The two dentaries (lower jaw bones) would be another load, and the cranium would be the last part lifted off the marsh. The sling loads went smoothly. In less than 20 minutes all three loads were lifted up the bluff, and the cranium was set directly onto our trailer. Video from the salvage effort can be seen on our Facebook page and Eric Keto from Alaska’s Energy Desk made an excellent short video summary of our effort, which can be seen here.

We managed to salvage 157 of the 168 bones. We are missing the two vestigial pelvis bones, one hyoid (throat) bone, and eight ribs we believe were taken (illegally) by people visiting the carcass before we got there. The skeleton is now safe at the University of Alaska Fairbanks campus where it will be further cleaned via burial in sand for a year. This allows bacteria to continue to breaking down the remaining tissue and oil. Once clean it will be the only (mostly) intact humpback whale skeleton available for research in Alaska. The long-term goal is to have it assembled and on display for everyone to appreciate.

This article originally appeared in the Alaska Chapter of The Wildlife Society’s Winter 2016 newsletter. View the newsletter here.

Article by The Wildlife Society