How Britain Tackles Tuberculosis in Badgers

Contentious, difficult and expensive: words often used to describe a teenager. But, these words are equally, if not more, applicable to the problem of tuberculosis (TB) in animals in the United Kingdom. This disease — caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium bovis — is one of the most pressing animal health problems in the U.K. and a massive headache for the country’s cattle farmers. TB is also a burden to the U.K. taxpayer who funds the majority of its management. Over £100 million ($150 million) is spent annually on TB surveillance, control and research. Yet, despite these efforts, the disease continues to spread and it’s unclear why.

What is clear, however, is that while cattle are domestic reservoir hosts of M. bovis, the European badger (Meles meles) is a wildlife reservoir, and the two can infect each other. Controlling the disease in cattle, which may subsequently also involve controlling badgers, is a contentious issue in Britain. The public reveres this rarely seen nocturnal creature entwined in British folklore and tends to resist efforts to remove the animals, leaving wildlife professionals and cattle farmers with some tough choices. While badgers may be black and white, how to effectively manage TB is a lot more complicated.

Badger Ecology — An Ideal Maintenance Host

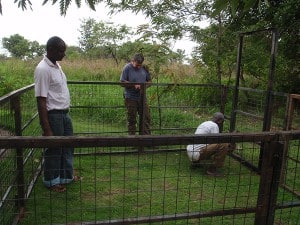

A badger is caught in a cage trap as part of an ongoing long-term study of TB epidemiology in Southwest England. Several traps baited with peanuts are placed around the entrances of burrows. Trapped badgers are transported to a sampling barn where they are anesthetized, identified, measured and sampled. After they recover from anesthesia, researchers release the animals back in the woods at the place where they were caught.

Image Credit: Julian Drewe

Tuberculosis has been present in cattle in the U.K. for more than a century. TB infections in humans, mainly from drinking raw milk, was a particular problem before the introduction of pasteurization in the early 20th century. By the early 1980s, TB in cattle had been almost eradicated. This was never fully achieved, however, and the incidence has since increased dramatically. The number of new herd outbreaks has doubled every nine years and the disease continues to spread geographically.

Meanwhile, researchers are doing their best to better understand badger ecology as well as the epidemiology of the disease in wild populations (Delahay et al. 2000, 2013). European badgers are ideal maintenance hosts for TB for several reasons:

They are social and territorial animals, living in stable groups that can range from two to as many as 23 adults. Badgers mark their territories with their distinctive latrines — collections of shallow pits in which they leave their feces. As a result, there are numerous opportunities for TB to spread among badgers whether from inhalation and grooming within the sett (a badger’s den) or through bite wounds during territorial disputes. Infected badgers may develop enlarged lymph nodes with abscesses that discharge bacteria. In addition, badgers can be long-lived — some survive up to roughly 12 years, although many are killed by vehicles long before this — which allows plenty of time for an infected animal to become infectious. Further, badgers with active TB lesions have been known to survive and successfully reproduce for many years.

Typically, conflict arises because badgers tend to live in the same areas of the country where cattle are farmed. Badgers mainly eat earthworms, which are abundant on pastureland. As a result, numerous opportunities exist for the two species to interact and for disease to spread. A recent study found that direct contact between cattle and badgers was rare at pasture, but indirect interactions such as visits to badger latrines by both species were common (Drewe et al. 2013). This might suggest that disease transmission may be more likely via these indirect means, or through other routes such as badgers gaining entry to barns housing cattle or feed stores. We still know very little about how, and how often, M. bovis infection passes between badgers and cattle in either direction, but despite this limited knowledge, researchers and policymakers have implemented several measures to try to manage the disease.

Managing TB in Badgers and Cattle

Current efforts to control TB in badgers focus on culling and vaccination — usually done without testing the animals’ infection status first. Below, we examine available disease management schemes, none of which is widespread.

Culling. Badgers in Britain fall under the Protection of Badgers Act 1992 and the Nature Conservation (Scotland) Act 2004 and, as a result, a specific license is required to shoot them. This might partly explain why the number of badger social groups in England was recently found to have doubled in the last 25 years, suggesting a large population increase.

The key question is, of course, whether culling badgers will lead to a reduction in TB incidence in cattle. A large-scale Randomised Badger Culling Trial, which ran from 1998 to 2006, investigated this very question (Independent Scientific Group on Cattle TB, 2007). Thirty areas each of approximately 100 square kilometers served as intervention (culling) or control sites. The trial unexpectedly found that if badgers were culled after a TB outbreak in cattle, the incidence of the disease among livestock in the area actually increased. Culling badgers before cattle outbreaks occurred reduced TB incidence, but this beneficial effect was offset by an increased incidence of the disease in surrounding un-culled areas. This detrimental effect appears to be due to surviving badgers mixing more and consequently spreading infection — a change in behavior referred to as a perturbation effect (Woodroffe et al. 2008). The trial’s main conclusion was that badger culling cannot meaningfully contribute to the future control of cattle TB in Britain. A subsequent review by a bovine TB eradication group came to similar conclusions in 2010 (Jenkins et al. 2010). Others have since argued that the benefits of culling may last longer than the negative effects.

An anesthetized wild badger is sampled as part of an ongoing long-term study of TB epidemiology in Southwest England. A large population of badgers has been trapped and sampled at this site for over 30 years, with many individuals sampled repeatedly throughout their lives. Here, researchers flush the badger’s trachea with sterile saline to provide a sample for bacteriological culture. The results help determine which badgers may be infectious.

Image Credit: Julian Drewe

Although the general public is strongly against culling, some farmers, vets and politicians support the practice. In an effort to reduce the costs of culling and temper the perturbation effect, Natural England — the government’s adviser on the environment — issued licenses in 2013 and 2014 that authorized badger culls over two areas of at least 150 square kilometers. An independent expert panel appointed to oversee the culls in 2013 concluded they were ineffective because they achieved a cull rate of less than 50 percent. The panel also questioned their humaneness given that more than five percent of badgers took longer than five minutes to die. Politicians in London debated the matter and then voted by a majority of 219 to one in support of a motion stating that these pilot badger culls had “decisively failed.” The government’s response was to continue the culls in 2014, this time without an independent expert panel to oversee them.

In general, badger culling — if done carefully and extensively over many years in targeted areas — might reduce TB incidence in cattle. Whether this could be sustained in a cost-effective and humane way over the long term is questionable.

Vaccination. In order to vaccinate badgers, biologists must first trap them in cages and inject BadgerBCG — a vaccine licensed to reduce TB lesions in badgers — into the animal’s muscle (Brown et al. 2013). This is relatively easy to perform on wild badgers without the need for sedation or anesthesia but is costly in terms of resources. For example, in the last three years, 4,000 badgers have been vaccinated at an estimated cost of over £600 ($900) per badger in one area of Wales (alongside cattle controls). Field trials in a different area of the U.K. indicated an approximately 75 percent reduction in incidence of positive serological tests in vaccinated badgers (Chambers et al. 2010). Further, vaccinating one-third of the adult badgers in an area resulted in a kind of herd immunity with a roughly 80 percent reduction in risk of infection in unvaccinated cubs (Carter et al. 2012). Data is currently sparse on if or how much badger vaccination might reduce TB incidence in cattle.

Vaccination of badgers has its limitations, however. Badgers are not usually tested before vaccination and, as a result, infected badgers may not benefit from vaccination. Because trapping badgers can be difficult and expensive, government agencies are currently developing an oral badger vaccine that can be placed in bait. Although oral vaccination worked well against rabies in many countries, there are some specific challenges associated with TB such as maintaining vaccine efficacy after it passes through the stomach; the cost of getting bait to badgers; and avoiding non-target species (especially cattle, which may subsequently test positive).

Testing. Northern Ireland is currently exploring a “test and vaccinate or remove” approach (TVR), where researchers catch live badgers and test them for TB. Individuals that test negative are vaccinated and released, whereas those that test positive are culled. Theoretically, this should result in less perturbation than a blanket cull. However, current tests for TB in live animals including badgers, cattle and humans are of low to moderate sensitivity, which could lead to many infected animals being released or vaccinated. As a result, this particular method of controlling TB may be limited until test sensitivity is improved.

Exploring Other Options

Over the years, wildlife managers, cattle ranchers and other stakeholders have tossed around a few other potential options to manage TB. Below are some ideas that come with their own set of challenges.

Vaccinating cattle. The European Union currently does not authorize vaccinating cattle against TB, noting that vaccination offers incomplete protection and vaccinated animals may subsequently test positive on the tuberculin skin test, the standard method to test for TB. This latter problem, however, can be overcome by the use of a diagnostic test — referred to as a DIVA test — that can differentiate infected from vaccinated animals. This would then allow cattle vaccination alongside a test-and-slaughter program (Chambers et al. 2014). Although field trials of cattle vaccination are a high research priority, experts estimate that it could take at least another eight years before a cattle vaccine could be deployed as a control measure.

Improving biosecurity. Biosecurity aims to prevent the introduction and spread of TB on farms. Researchers have explored several measures to achieve this including testing and quarantining new cattle, installing electric fences around farms to keep cows from grazing around badger latrines, and building better gates on farm buildings to keep badgers out of cattle feed stores. Although common sense and mathematical models suggest all these efforts should reduce TB incidence on farms, evidence to support this is sparse, and farmer uptake of biosecurity is varied.

Using antibiotics. Treating badgers or cattle with antibiotics is simply not an option. Widespread and long-term prophylactic or therapeutic use of multiple antimicrobials in cattle or wild badgers would be logistically challenging, not to mention the cost and risks of bacteria developing resistance to the antibiotics.

Doing Nothing. Strange as it may seem, there is a case to be made for doing nothing — after careful consideration of the options rather than ignoring the problem and hoping it will go away. Testing and compensating for tuberculosis in cattle consumes over 90 percent of the current U.K. animal health surveillance budget. Perhaps resources could be better targeted on other diseases where they are more likely to have a bigger benefit to health and welfare. However, support for this argument is limited, probably because controlling TB is an entrenched viewpoint, and there are concerns about zoonotic risk and effect on trade.

Future Prospects

There is potential for farmers in the U.K. to take more responsibility for the direction of the national TB management strategy. There’s evidence of success in that approach in countries such as New Zealand where farmers played an active role in controlling TB in brushtail possums (Trichosurus vulpecula). There are some key differences between the two cases, however: In New Zealand, farmers had more say in management strategies compared to farmers in the U.K. and, perhaps more important, the brushtail possum is an introduced species in New Zealand unlike the European badger, which is indigenous and protected in the U.K.

Still, most people agree that a comprehensive and multidimensional approach is needed if TB in cattle is to be effectively managed. This does not, however, necessarily mean that every possible disease control option should be used. Instead, it’s best to carefully assess the potential benefits and costs of each possible solution and choose the best combination, while considering the costs and ethics of any intervention effort. After all, disease control is ultimately a political decision and, even as we continue researching the issue and tackling related complexities, we must remember that TB eradication is a long way off.

Image Credit: Jemima Margo Elveera

Julian Drewe, PhD, is a lecturer in veterinary epidemiology with a particular interest in wildlife health at the Royal Veterinary College in London, U.K. WDA is all wildlife diseases, all conservation, all one health, all the time.

The Wildlife Professional is a TWS member benefit. Join TWS to take advantage of this and other member benefits.

John McDonald

John McDonald Mike Conner

Mike Conner Fidel Hernández

Fidel Hernández Art Rodgers

Art Rodgers