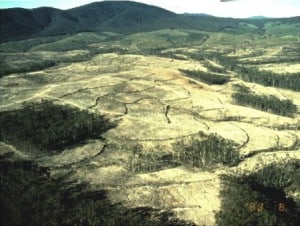

The dusky gopher frog is one of the most critically endangered frog species in North America, living around only a handful of ponds in Mississippi.

But wildlife managers have been busy for most of the year in an effort to reintroduce the frogs to a pond in the Mississippi Sandhill Crane National Wildlife Refuge.

“It’s considered one of the 100 most endangered species in the world,” said Angela Dedrickson, a wildlife biologist at the refuge, in reference to the dusky gopher frog (Rana sevosa) being listed on the most threatened species list published by the Zoological Society of London in 2012.

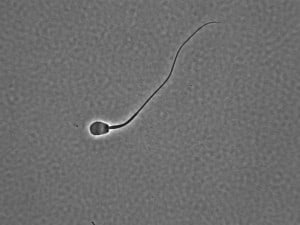

Dusky gopher frogs tend to live in burrows sometimes dug out by tortoises or small mammals. Females lay their eggs in temporary ponds that pop up during wet seasons, but they are picky — the ponds have to be around 18 inches deep, with no fish but with some kind of vegetation on which they can attach their eggs. There are only 100-200 adult frogs still in the wild, concentrated mostly in the Desoto National Forest in Mississippi.

Researcher Ross Ketron releases dusky gopher frogs into a pond in the Mississippi Sandhill Crane Wildlife Refuge. It will take around 2.5 years before the frogs will be able to reproduce. Image Credit: Angela Dedrickson

But Dedrickson has been working with the Desoto National Forest, the U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service, the Mississippi Department of Wildlife, Fisheries and Parks, Western Carolina University and the Nature Conservancy to raise gopher frog eggs and reintroduce them to the Sandhill Crane refuge.

Earlier this year, researchers collected egg masses from a pond in the Desoto National Forest, hatched them and raised them in labs for several months as the tadpoles transformed into juvenile frogs. They started to release the juveniles into a pond surrounded by a drift fence that allowed researchers to monitor frogs going in and out as soon as they became large enough over the summer.

“We had a 79 percent success rate from the tadpoles that were delivered to what was meted out and delivered in the pond,” Dedrickson said. “I’m really looking forward to seeing how successful they are.”

It will take a couple years before they can tell if their strategy is working though. Frogs will leave the pond to find burrows, but many will return to mate. Males can reach sexual maturity in a year and a half, but it takes females an average of 2.5 years. “[The males] will be a little disappointed for now but they’ll be very happy in a couple of years,” Dedrickson said.

The goal is to have a self-sustaining population in the pond — at least 100 breeding adults — so the project will continue next year. If successful, researchers may expand the reintroduction to other ponds.