Share this article

Black-Footed Ferrets Inseminated with Frozen Sperm

One of the rarest mammals in North America is slowly recovering because of scientists’ successful efforts to inseminate females with frozen sperm.

Scientists with Lincoln Park Zoo along with partners from various organizations such as the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute (SCBI), U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and others, used semen frozen with liquid nitrogen that was 10 to 20 years old to inseminate female black-footed ferrets (Mustela nigripes), a critically endangered species.

“There was already a genetic bottleneck from this population. There are also problems maintaining the genetic health of the species,” said Rachel Santymire, the director of the Davee Center for Endocrinology and Epidemiology at the Lincoln Park Zoo, a member of The Wildlife Society and co-author of a paper recently published in Animal Conservation.

Santymire said a genetic bottleneck can make it difficult for the species to survive. There would also be a risk for inbreeding depression if there are no new genes introduced, so it was necessary to avoid this constant loss of genetic diversity over time by introducing this older, frozen sperm.

Black-footed ferrets were saved from extinction in the mid-1980s when scientists trapped the 24 ferrets that were left in the wild. The species faced the threat of loss of prairie dogs — their primary prey — to agriculture, livestock and the construction of cities as well as the plague, which was brought to the United States from China by rats that were transported on ships in the early 1900s. Of the 24 ferrets, eventually six of them died from either canine distemper or the plague, according to Santymire. The animals, which exist in the Great Plains and are found only in the U.S., were left with a global population of 18.

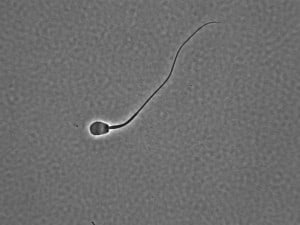

An enlarged image of previously frozen black-footed ferret sperm. Researchers used older frozen sperm to help maintain genetic diversity of the endangered species.

Image Courtesy: Rachel Santymire

These 18 ferrets produced only seven surviving offspring. These became the population’s founders. One particular founder was recognizable due to a large scar across his face that he likely received from battling a prairie dog. Although this particular founder has been dead for about 20 years, the researchers froze his sperm and used it in this study to inseminate members of the population.

While 135 kits have been born through artificial insemination, this is the first time researchers used frozen semen. Eight kits were born from the frozen sperm. “This is the first time we can show long-term storage is still successful,” Santymire said.

However, the insemination had its share of challenges. Freezing and then thawing semen causes the quality to decline over time. But it’s still a method that can be successful and even applied to other species. “You can routinely use this method instead of moving individuals between facilities,” she said.

Santymire and her team continue to bank sperm samples for the black-footed ferret population since males are not well-represented and their genes are valuable. The goal of their program is to maintain the ferrets’ genetic health and to produce enough of them to release them into the wild. “There are 300 to 400 in the wild currently,” Santymire said, adding that there are 24 reintroduction sites including active and new ones.

Santymire hopes her team’s work with black-footed ferrets will be a model species to help bring back other endangered carnivores. “I like how the zoo is in this for the long haul with this species,” Santymire said. “They are one of our native species, and we have put in so much effort to save them.”

Header Image: A black-footed ferret stands in a prairie dog burrow. Conservation scientists with the Lincoln Park Zoo were able to artificially inseminate female ferrets with 10 to 20-year-old frozen sperm.

Image Credit: Rachel Santymire