Digging for Answers: How One Wyoming Native Seeks to Understand Another

By Brian Zinke, Communications Committee Chair/Newsletter Editor

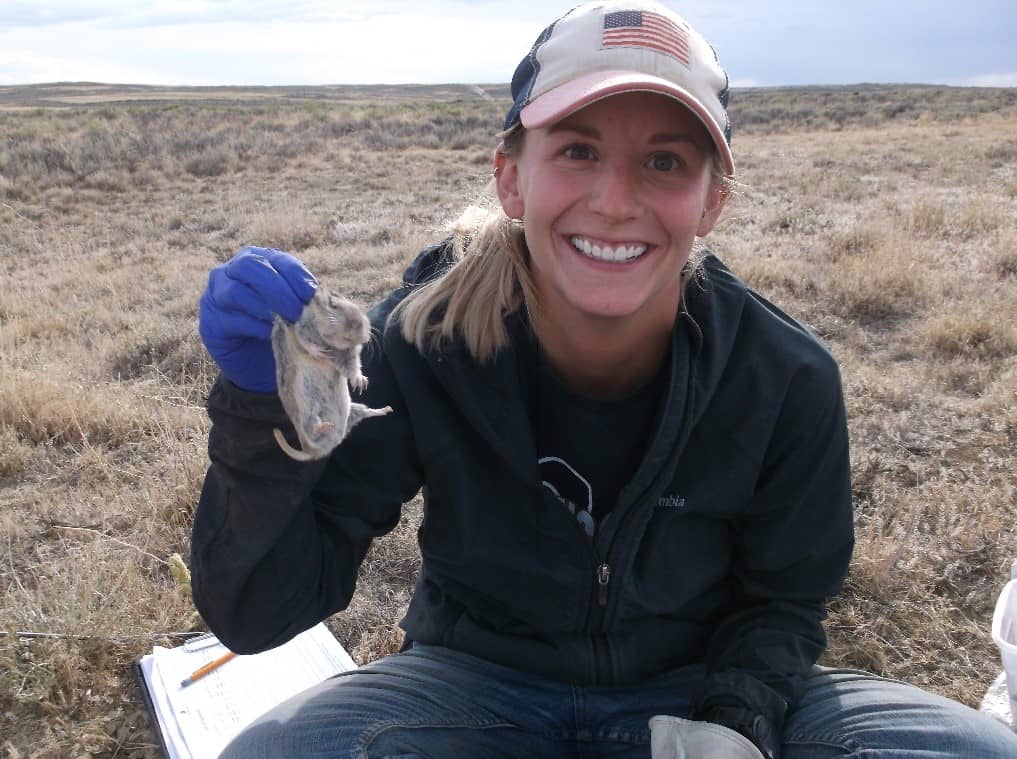

Britt Brito with a collared Wyoming pocket gopher. Photo by Cody Burdett.

Wyoming is known for its diverse and abundant wildlife, ranging from the iconic bison and wolves of Yellowstone to the pronghorn that seemingly outnumber the people in the Cowboy state. Tourists flock to Wyoming from all over the world to see these breathtaking species in their natural habitats. But there is one species that is especially unique to Wyoming that most tourists, or even biologists, have never laid eyes on. The Wyoming pocket gopher (Thomomys clusius) is endemic to Wyoming, meaning it occurs nowhere else in the world. It is one of the least studied mammals in North America, for several reasons: it is geographically constrained to an area about 30,000km2, spends almost its entire life below ground, and pocket gophers are notoriously hard to capture. Despite these difficulties, research on this unique species is underway at the University of Wyoming (UW).

“When I began looking into the details of this project, I became fascinated with the Wyoming pocket gopher,” says Britt Brito, a graduate student at UW and a Wyoming native herself. “So little information is known about a species found in our own backyard and as a result, many assumptions about its ecology have been made based on other pocket gopher species.” Brito is seeking to fill important knowledge gaps in Wyoming pocket gopher ecology to better inform conservation decisions. Her research is focused on how natural gas infrastructure affects Wyoming pocket gopher occupancy and vital rates, as well as possible hybridization with the northern pocket gopher (T. talpoides).

Habitat typical of Wyoming pocket gopher captures. Keinath et al. (2014) found an association between Wyoming pocket gophers and areas containing Gardner’s saltbush (Atriplex gardneri), and winter fat (Krascheninnikovia lanata). Photo by Britt Brito.

Mounds in typical Wyoming pocket gopher habitat. Photo by Britt Brito.

“I conduct my research predominantly in the Red Desert in south-central Wyoming, where fossil fuel and mineral extraction occur throughout the region,” Brito says. “We believe Wyoming pocket gophers are sensitive to habitat fragmentation because of their limited dispersal ability. However, their entire geographic range is confined to areas in which energy development is occurring or is slated to occur in the next 15 years, resulting in an increase in roads, pipelines, and other disturbances which could further limit dispersal.”

Energy development and its effect on wildlife populations has been and continues to be a major topic among conservation organizations, industry stakeholders, and government agencies. However, the species usually discussed in those circles are the more well-known ones, such as Greater Sage-grouse (Centrocercus urophasianus). Despite being a species humans rarely see, it is important that we study and conserve the Wyoming pocket gopher because it plays a pivotal role in many ecological processes.

“Pocket gophers are excellent ecosystem engineers impacting the ecosystem both directly and indirectly,” says Brito. “However, their alterations to the physical environment are largely overlooked because the indirect effects are difficult to quantify and typically can’t be seen aboveground. As subterranean mammals, they form complex tunnel systems belowground typically at depths containing the highest density of roots. While foraging on plant roots and excavating new tunnels, pocket gophers play a large role in soil dynamics. Studies have shown that pocket gophers increase nutrient redistribution in soils and increase nitrification rates.”

She continues, “They also assist with water movement through the collection of snowmelt and other sources of water in the tunnel systems. On the surface, water and sediment from [pocket gopher] mounds may accumulate, forming rich areas for new plant growth.”

Brito is finishing up her second year of the study, with one more field season left. She live-traps pocket gophers from June ‒ October, collecting genetic samples and recording body measurements, age, sex, and physical appearance, such as pelage color and occurrence of a post-auricular patch (which allows her to determine species). In 2018, she also started fitting radio-transmitter collars to pocket gophers to better estimate survival.

So far, the project is going really well. “Over the past two seasons we have captured over 70 pocket gophers,” says Brito. “One unexpected thing we have seen is the presence of both northern and Wyoming pocket gophers at a site. We saw this once last year; however, the gophers were several hundred meters apart. This year we have captured both species within 20 meters of each other, which was unexpected. I am very interested to look at our genetic data to see if these species are hybridizing.”

Above: Wyoming pocket gophers going through the process of data collection, PIT insertion, tissue collection, and attachment of the radio-transmitter collar. Photos by Britt Brito.

Capturing such an elusive species can be exhilarating and incredibly satisfying, but it is also very time and labor-intensive. “Successfully capturing animals has been the most difficult part of the project so far,” Brito admits. “Our traps are frequently back-filled by gophers, leaving us emptyhanded and frustrated. However, persistence is key!”

In addition to building upon the limited knowledge base of the species, one of Brito’s goals is to develop a real-world solution to aid in the management of the species. She understands that a state agency will not be able to dedicate the vast resources needed to conduct such intensive trapping surveys on a consistent basis. So she added another part to her project: determine a quicker method to assess an area for pocket gophers.

“I also record a variety of tunnel measurements from capture locations,” she says. “These measurements include tunnel diameter and tunnel depth. I hope this data, in conjunction with habitat data, will allow researchers and biologists to accurately predict which species is present without having to go through the time and labor-intensive process of trapping.”

Brito only has one year left of graduate school but hopes her research will help advance the conservation of her fellow Wyoming native and have a lasting impact. “I’m optimistic that with all the new information we are learning about this species we are going to be able to develop useful tools for state biologists to monitor this species in the future.”

The Wyoming pocket gopher is listed as a Tier 1 Species of Greatest Conservation Need in Wyoming ‒ the highest rating the state can give. However, after petitions were filed in 2007 and 2016 with the US Fish and Wildlife Service, the Service determined it did not warrant protection under the Endangered Species Act.

Brito with a Wyoming pocket gopher. Photo by Cody Burdett.

Brian Zinke, AWB®, is a pygmy rabbit biologist for the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, where he plays an integral role in the restoration of the endangered Columbia Basin population. Prior to that, he served as a Nongame Biologist with the Wyoming Game and Fish Department for nearly three years.

Brian Zinke, AWB®, is a pygmy rabbit biologist for the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, where he plays an integral role in the restoration of the endangered Columbia Basin population. Prior to that, he served as a Nongame Biologist with the Wyoming Game and Fish Department for nearly three years.