Lauren Reeves knew she loved the fish tank in her parents’ house, but attending the TWS Annual Conference in Albuquerque, New Mexico made her think about fish in a different way. Maybe, she realized, she could turn her love for fish — and other animals — into a career as a wildlife biologist.

“It definitely made me consider a career in wildlife more,” said Reeves, a freshman biology major at the University of New Mexico. “Before I didn’t know what I was going to do. I just knew that I wanted to work with animals.”

Reeves was one of 33 students who attended the conference as part of Newcomers Day, a program intended to bring students from minority-serving institutions to help get them interested in wildlife careers.

“These smaller schools were completely getting left out of the picture,” said Doan-Crider, an adjunct professor at Texas A&M University’s department of ecosystem science and management and the recipient of the 2015 TWS Diversity Award.

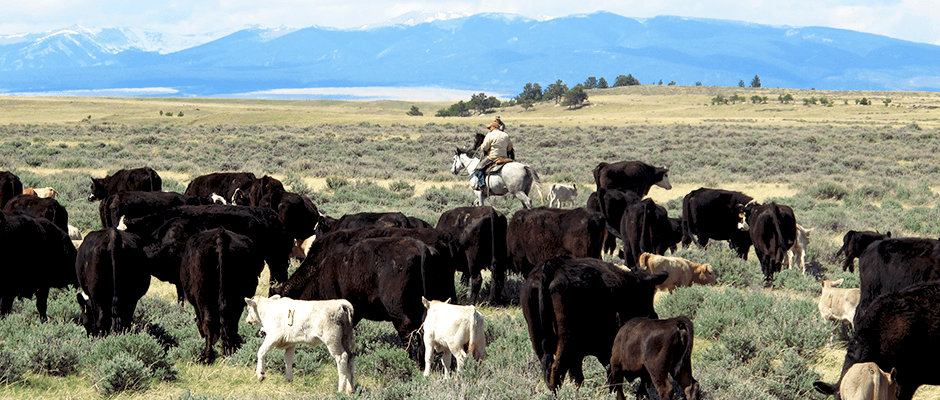

Doan-Crider is director of Animo Partnership in Natural Resources, a nonprofit that focuses on increasing diversity in natural resources fields. When she first proposed the idea of Newcomers Day, she was also thinking about fish — or about fish ladders.

To get fish up a river, they need to follow the steps along the way. When she looked at how to get more minorities into wildlife and other natural resources careers, she found a long list of “disconnects” from the university level on up that stood in the way.

There was no lack of interest, she found. In the Southwest, many of the schools that serve large numbers of minorities — particularly tribal colleges and schools with large Hispanic student bodies — are located in areas with easy access to natural resources. Ever since the Standing Rock pipeline controversy, she said, interest in these issues on tribal lands has been especially strong.

“There’s just been an upsurge of interest from young people who want to be able to manage their own resources,” she said. “They want to have an impact in their own communities.”

But many of these minority-serving institutions are smaller, with smaller budgets, Doan-Crider said. Their biology departments aren’t geared toward natural resource careers and they lack the sort of activities that could introduce students to wildlife, range, forestry and fisheries jobs.

In a collaborative effort with St. Edward’s University in Austin, Texas and the U.S. Forest Service, Doan-Crider and her team came up with the idea of a Newcomers Day — one day at the national conferences of natural resources professional organizations, when students from nearby minority-serving institutions could attend for a reduced rate and be introduced to the profession.

The Wildlife Society’s Annual Conference in Albuquerque, New Mexico last month hosted the first Newcomers Day, welcoming students from nearby colleges with a one-day pass for $100. Funding to help offset the costs for students was provided by the Forest Service. Students came from about a dozen colleges, universities and organizations, including Southwest Indian Polytechnic Institute, Navajo Technical University and Northern New Mexico College.

The pass allowed them to attend the Ready Set Go! Federal Employment Workshop organized by the Animo Partnership, sit in on other sessions and network with conference participants.

“Most of the students felt it was super-beneficial for them,” Doan-Crider said.

For some, it came with the bad news that their programs lack the coursework government agencies require, she said, but that’s information they need so they can consider getting that experience, either at other institutions or at the graduate level, to be able to land a job in a wildlife profession.

And it’s not just, wildlife, Doan-Crider said. Her organization is hoping to pursue similar Newcomers Day programs with other professional organizations, such as the Society for Range Management and the Society of American Foresters, where students face similar obstacles.

“We could help solve our workforce diversity issues if we could increase minority participation at the lower levels of the fish ladder and help students understand and meet the employment requirements,” she said. “How do we do this? We get them to our conferences.”