Adrián Caballero and his colleagues released tracking dogs late one February morning in the hilly jungle terrain of San Luis Potosi, Mexico, and from there, the chase was on. “Machete en mano,” they sometimes ran along thin game trails, sometimes sliced their way through thick foliage, following the sound of the dogs’ barking as best as they could, in pursuit of a jaguar.

After nearly four kilometers of an intense, “exciting” chase, the team finally caught up to the dogs, which had chased their quarry up a tree. Despite the apparent exhaustion of the jaguar, Caballero was taken back by the fierce look in its eyes. “It’s a magnificent beast,” he said. The wildlife managers prepared the tranquilizing dose in the gun, but “I was nervous—I think I was shaking,” he recalled.

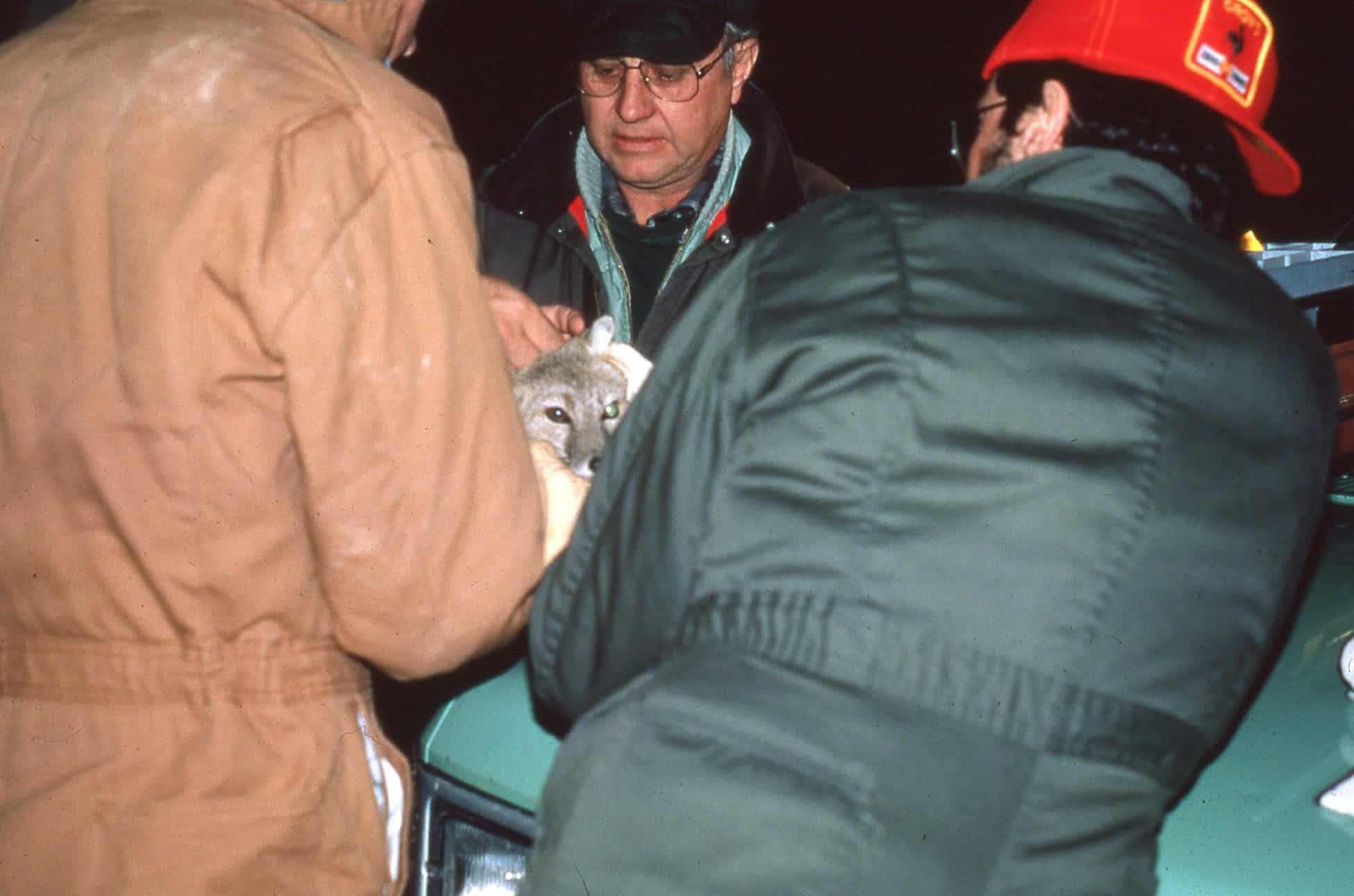

Once the dart hit the animal, the team prepared a large blanket to catch its fall, similar to the way firefighters capture people jumping from burning buildings.

The trouble was, the jaguar (Panthera onca) became unconscious up in the tree, perched on a fork of branches. They had to cut the limb off the tree and tie a rope to the jaguar so it would fall properly into the blanket without injury.

The operation worked. On the ground, they measured the jaguar, fitted it with a GPS tracking collar, took a blood sample, administered a drug that reversed the tranquilization and woke the cat up. They backed up 10-15 meters and watched as it woke up and took off. Only then did Caballero realize how scratched up he was from barreling through spiny agave-like guapilla plants in their pursuit.

“In the moment, I didn’t even sense it,” he said.

It was 2016, and Caballero, who was working on his PhD at the Postgraduate College of San Luis Potosi at the time, and his colleagues were capturing jaguars. They were fitting them with tracking collars in an effort to learn more about how they prey on livestock in the state of San Luis Potosi in northeastern Mexico. These kinds of predations can lead to conflict with the ranchers that live in the area—problems that could be dangerous for humans and sometimes lethal for jaguars.

Tracking jaguars

In their study published in Studies on Neotropical Fauna and Environment, the team built on 10 years of previous trail camera work on jaguars in the area conducted by Octavio Rosas-Rosas, a biology professor at the Postgraduate College of San Luis Potosi and a co-author on the study. They started in 2015 by putting out snares to capture jaguars, but this technique didn’t work. The next year, they set out with tracking dogs in search of paw prints, scat and other traces of jaguars in areas where the trail cameras had captured recent photos.

In total, the team captured three jaguars in 2016, though one of them went missing only a few days after it was collared—Caballero said it may have been poached.

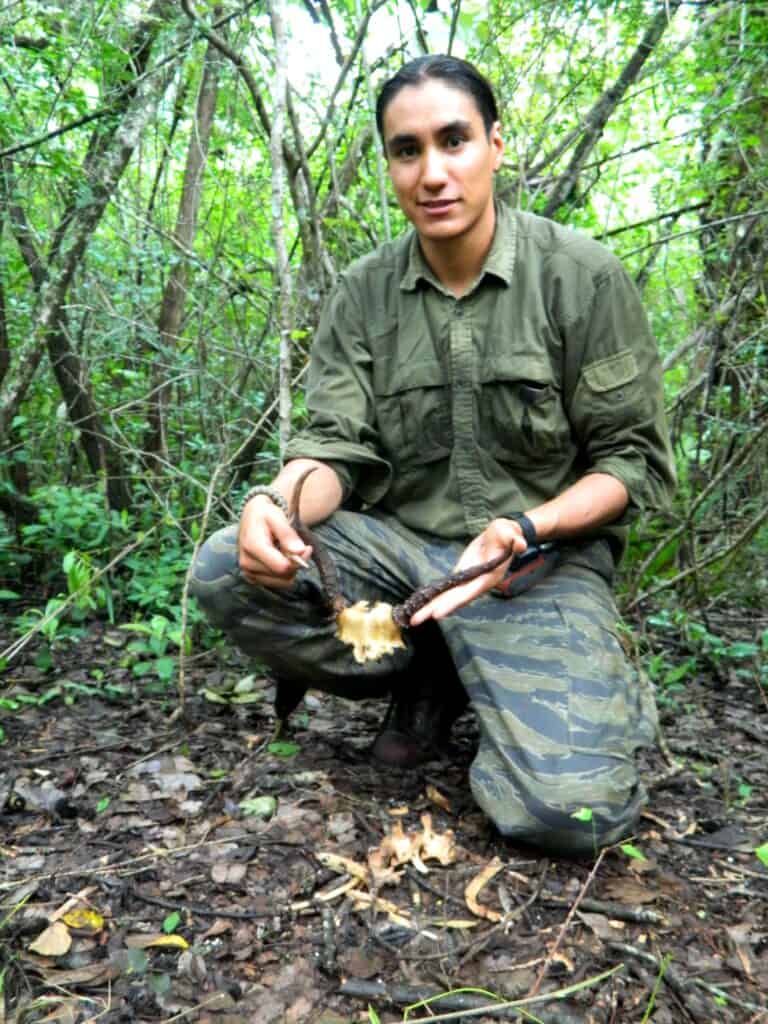

They monitored the GPS data from the two cats that remained and watched for location clusters indicative of the cats making a kill. The team then set out to find the remains of any prey in these areas—Caballero described them as looking something like a crime scene investigation, with hair, pieces of bone and some stomach. “We could see the struggle, and we interpreted that,” he said.

The researchers’ analysis revealed that the most common wild prey were javenilas (Tayassu tajacu) and white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus).

They also found that jaguars preyed on cows, though not to the same extent as javelinas or deer. In fact, jaguars only preyed on cattle during the dry season.

Why do jaguars prey on cows?

Caballero said this may be due to a lack of water resources in nearby wildlife reserves. The jaguars may be using artificial water sources placed by ranchers for cows and donkeys, putting them in closer proximity to livestock. When the opportunity arises to take a yearling cow, it is likely an easier target than a javelina for a jaguar.

Other factors may also play a role in jaguars preying on livestock. Many ranchers in the area don’t control their cattle very closely, letting them wander freely in large areas. When cows or donkeys die of disease or other causes, ranchers often leave them on the landscape—in fact, Caballero’s study determined that about half of the eight cattle were scavenged rather than killed.

Caballero said that increased education among farmers in the area could help to reduce the attraction of jaguars to ranch areas. To reduce the likelihood of jaguar predation, ranchers could bring cattle closer to houses during the night and clean up the carcasses of dead cattle.

Caballero, now the CEO of Wildlife Management Mexico, a nonprofit consultancy, said his lab has worked on improving public education about ranching through workshops funded by the United Nations Development Program and the National Commission for Protected Natural Areas. Ranchers have also received money for cables to build cattle pens as well as funding and education on feeding the cattle with things like ground-up corn stalks, leaves and cobs, thereby keeping the cows closer to the houses and less likely to venture into wilder areas where they may encounter jaguars.

Caballero said many of the locals were very curious to hear the results of their research. “I’m glad about that,” he said.

This photo essay is part of an occasional series from The Wildlife Society featuring photos and video images of wildlife taken with camera traps and other equipment. Check out other entries in the series here. If you’re working on an interesting camera trap research project or one that has a series of good photos you’d like to share, email Josh at jlearn@wildlife.org.