Share this article

Wildlife Featured in this article

- Arizona tiger salamander

Wild Cam: Climate change may exacerbate salamander cannibalism

Arizona tiger salamanders eat each other more when water gets scarcer

Climate change may be turning more Arizona tiger salamanders to cannibalism.

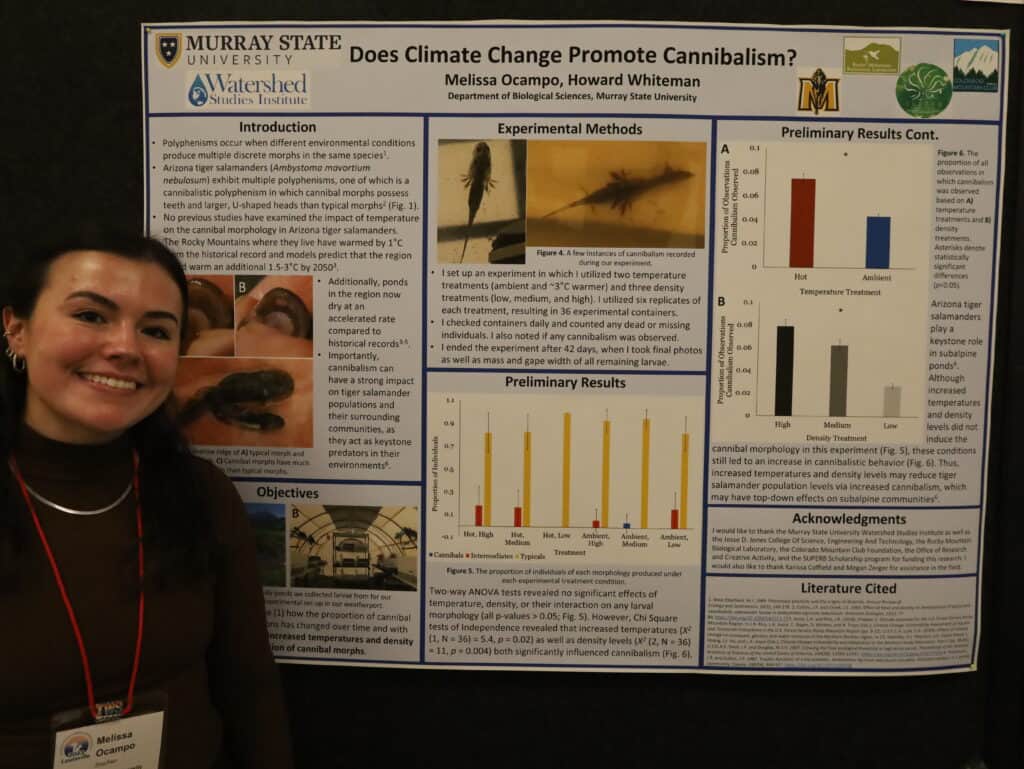

Many salamanders occasionally eat each other. “Cannibalism in salamanders isn’t a unique thing—pretty much all salamanders will cannibalize,” said TWS member Melissa Ocampo, a master’s student in watershed science at Murray State University in Kentucky.

Scientists, including Ocampo’s supervisor Howard Whiteman, had conducted research in the 1990s on cannibalism in Arizona tiger salamanders (Ambystoma mavortium nebulosum), a subspecies of western tiger salamanders (A. mavortium), in Colorado, where they are also found. That research revealed that Arizona tiger salamander larvae have two different body forms—a typical body type and a cannibal morph, which includes individuals with “super wide mouths with crazy sets of teeth” that help them eat other tiger salamanders, according to Ocampo. Once they metamorphose into adults, they lose these cannibal morph features.

Those morphs can be affected by the environment where they live. In the Rocky Mountains of Colorado near Crested Butte, many of the ponds these salamanders live in are seasonal. They appear from meltwater in April and May, before slowly drying up in the summer. The females lay eggs to coincide with this period, but the seasonal nature of the waterbodies puts a deadline on development for the young salamanders. “Larvae in the temporary ponds have to metamorphose before the pond dries,” Ocampo said.

The Rise of the cannibals

Whiteman’s earlier work had found that as salamander density increases in these ponds, the ratio of cannibal morphs increases. This means that if the ponds dry up more quickly, more cannibals begin to appear. He also found that a higher density of invertebrate prey seemed to result in more cannibal morphs. More invertebrate prey items lead to more varied sizes in salamanders, which is also associated with the cannibal morph.

By contrast, permanent ponds usually don’t host any cannibal morph tiger salamanders.

But since this work in the 1990s, research had slowed down on cannibal tiger salamanders, and nobody had looked at how temperature or increased drying rates influence the cannibal morphology.

As part of her master’s work, Ocampo resurveyed the ponds and populations her supervisor had examined using the same techniques as the previous research. She and her colleagues ran nets through the ponds to capture larvae to get salamander counts. They also counted the ratio of cannibal morphs versus typical morphs.

They also estimated the invertebrate density by dropping a cylindrical garbage can with the bottom cut out into the pond, similar to what Whiteman did previously. They would then scoop out all the invertebrates and salamander larvae inside.

Climate cannibals?

On a poster at The Wildlife Society’s 2023 Annual Conference in Louisville, Kentucky, Ocampo described how the surveys have so far confirmed many of Whiteman’s findings in the 1990s. Ocampo’s work is still ongoing, but she predicts that the ratio of cannibals may be higher now than it was 30 years ago, since the ponds are drying up earlier due to climate change. There has also been less snowpack accumulation, which ultimately leads to less water in the ponds during the spring and early summer.

To supplement this work, Ocampo also ran experiments with salamanders. In the summers of 2022 and 2023, she and her colleagues placed salamander larvae in tanks with different treatments. They left one at ambient temperature, while increasing the other by three degrees Celsius. The team also included three different density treatments as a proxy for what would happen when ponds dried up faster or slower—bins with four, eight and 12 salamanders each.

Over a six-week period, she and her colleagues checked the salamanders for morphological changes as well as evidence of cannibalism.

Ocampo didn’t find any difference in the number of cannibal morphs between the various treatments. But they did find cannibals disguised as typical morphs. Salamanders in the bins with higher densities and hotter temperatures cannibalized each other more.

Researchers still don’t understand all the factors that may play a role in cannibalism and in the morphological changes to a cannibal type.

But Ocampo’s work on the topic is ongoing. Arizona tiger salamander populations are decreasing in parts of their range due to the introduction of sport fish in some of their breeding ponds. If introduced fish aren’t around, the Arizona tiger salamander is a keystone species in the Rocky Mountains, acting as top predators in fishless ponds. A better understanding of the causes of cannibalism can help researchers determine the effects of hotter future climates on population and ecosystem health in the Rockies.

This photo essay is part of an occasional series from The Wildlife Society featuring photos and video images of wildlife taken with camera traps and other equipment. Check out other entries in the series here. If you’re working on an interesting camera trap research project or one that has a series of good photos you’d like to share, email Josh at jlearn@wildlife.org.

Header Image: An adult Arizona tiger salamander. Credit: Melissa Ocampo