Share this article

Wildlife Featured in this article

- Black-footed cat

- Leopard

- Springhare

- Cape ground squirrel

- Aardvark

- Aardwolf

- Bat-eared fox

- Cape porcupine

- Black-backed jackals

- Caracal

- Meerkat

Wild Cam: Black-footed cats depend on rodent burrows

Researchers learn more about life underground of one of Africa’s smallest and rarest cats

Black-footed cats depend on the burrows that other animals dig in the grasslands of southern Africa.

But these vulnerable, tiny cats—which may be the rarest wild felines in Africa—may lose their habitat if the South African springhares that dig these holes are locally extirpated from some areas.

“The most important thing I found is that we need to preserve springhare if we want to save the black-footed cat,” said TWS member Hal Brindley, website administrator for the American Chestnut Foundation.

Cat mission

Black-footed cats (Felis nigripes), which the International Union for Conservation of Nature lists as vulnerable, are found in southern Africa, mostly in Namibia, South Africa and Botswana. These felines are about a third the size of a house cat and are hard to detect due to their tiny size and nocturnal lifestyle.

When completing his master’s degree at the University of Cape Town in South Africa, Brindley decided to focus his work on black-footed cats, which were understudied compared to larger felines like leopards (Panthera pardus) or lions (P. leo) in the region. “Plus, they are really ridiculously cute, which helps,” he said.

As detailed in a presentation at The Wildlife Society’s 2023 Annual Conference in Louisville, Kentucky, Brindley and his colleagues conducted their research at a field site on private property used for sheep grazing in Grunau, a small settlement in southern Namibia. The study, which involved collaboration with conservation organizations, including the Black-footed Cat Research Project Namibia and the Black-footed Cat Working Group, lasted for four weeks in 2022.

When the team started, six known female cats roamed the 70,000-hectare site, but they found one of them dead on the first day of the study. These cats were all fitted with VHF tracking collars for ongoing research. Four of the surviving cats were either pregnant or had kittens.

The team drove around, tracking cats via their VHF collars. This involved a lot of traveling—despite their small size, black-footed cats have a home range of about 40 square kilometers in this area. Once the researchers got close to a signal, they started off on foot. They recorded where the cats denned during the day and followed them by vehicle at night. The researchers would get within 20 meters of the cats, though the animals would sometimes circle back and come right up to the researchers’ truck.

While it wasn’t their main focus, Brindley watched the cats hunt birds and rodents, though the small animals were easy to lose in the grass. “What’s really weird about these cats is that they have a really high metabolic rate,” he said, comparing their flitting movements to chipmunks. “Everything was sped up.”

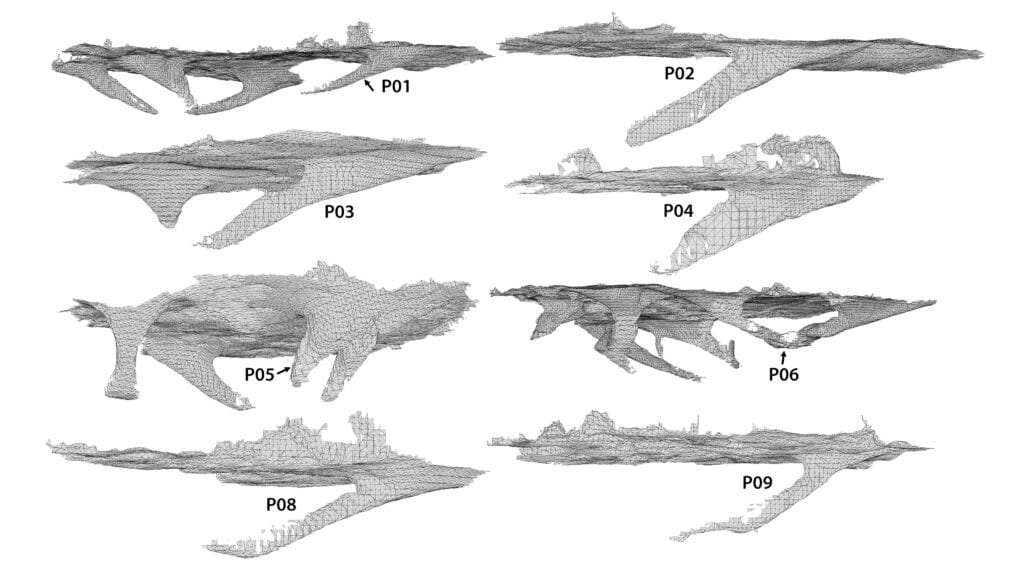

Once they verified and recorded which burrows the cats used, they waited for the felids to leave and measured the size and dimensions of the openings using a Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) scanner on an iPad.

Cat videos for science

Before getting out in the field, Brindley had indulged in numerous YouTube videos of house cats squeezing through small openings. He’d taken rough measurements of what spaces cats could get into based on their size as a way of estimating how black-footed cats might fit into burrows of various dimensions. He estimated that black-footed cats might prefer burrows with openings of 10–20-centimeter diameters.

His cat video calculations proved fairly accurate when Brindley analyzed his field data. In their study area, black-footed cats almost entirely used the burrows that springhare (Pedetes capensis) dug.

Springhares, Cape ground squirrels (Xerus inauris) and aardvark (Orycteropus afer) all dig burrows in this area, while aardwolves (Proteles cristata), bat-eared foxes (Otocyon megalotis), Cape porcupines (Hystrix africaeaustralis) and Cape foxes (Vulpes chama) modify the burrows springhare and aardvark dig. The size of springhare burrows, before modifications, are between the size of aardvark and ground squirrel burrows. While springhare don’t face threats overall, sport hunters target springhares, while farmers often consider them a nuisance.

The cats inhabited an average of 11 different burrows during the four weeks that Brindley and his team were in the field. Cats spent an average of 2.2 consecutive days in a den before moving to a new one. The ones with kittens would use a den for an average of six days but never return to the same den after they left it. That may have been a tactic to evade predators after the cat left its scent there, Brindley said.

Once their kittens were six or seven weeks old, the adult females would also drastically change their strategy, shifting dens every day. Brindley said this likely reflects the fact that the kittens come along with them on their nightly hunts—the family would stop wherever they ended up around dawn.

Most burrows the cats used seemed abandoned. In other situations, Brindley speculated that they didn’t seem to be affected by the presence of the intruders. Despite the name and their rabbit-like appearance, springhares are actually rodents. These small creatures dig vast burrow systems—they can be 30 meters in diameter, with passages heading off in every direction and a dozen different entrances. The cats typically didn’t go too deep inside, and only used a single entrance, so the springhares were likely able to continue using the burrows.

While black-footed cats elsewhere may use other animals’ burrows, or even termite mounds that aardvarks excavate, this research reveals that black-footed cats are often heavily dependent on springhare in this part of Namibia. Brindley said this is likely because larger burrows aardwolves and foxes dig might not be as safe for the felines, especially when the kittens are young and left alone at night. Predators like black-backed jackals (Canis mesomelas) or even caracals (Caracal caracal) might be able to enter.

The low-intensity, rotated grazing of ranchlands creates the kind of grassland habitat favorable for the cats and their rodent prey, Brindley said. These cats aren’t really persecuted, as humans hardly see them—accidental capture in traps or via poisoned baits set for other small predators or jackals might be the biggest threat they face directly from humans.

But sheep farmers also kill jackals, such as the one above eating a meerkat (Suricata suricatta), over fears these canids may kill livestock, which also removes a potential predator of black-footed cats. Working with farmers to conserve springhare habitat may be the best way to conserve black-footed cats, Brindley said.

Header Image: Black-footed cats are about a third the size of a house cat. Credit: Hal Brindley/Travel For Wildlife