The Wildlife Society’s 23rd Annual Conference in Raleigh, North Carolina, promises to be one of our organization’s biggest and best events ever! Early projections indicate that the October 15-19 event will draw at least 1,800 professionals and students.

Over the next two weeks, we’ll be unveiling our full lineup of workshops, plenary/keynote, symposia and panel discussions that will be a portion of the more than 500 educational opportunities available to you as a conference attendee. Our education and training program will continue the theme of our jointly-hosted workshop at the recent North American Wildlife and Natural Resources Conferences—reconnecting wildlife science and management—while spotlighting how effective partnerships are making a big impact on wildlife management and conservation.

Workshops will be conducted on Saturday, October 15. Six of the 12 workshops are highlighted below with abbreviated general descriptions. We’ll preview the rest of our amazing lineup of workshops on Tuesday, April 12.

Complete abstracts will soon be available at our conference website. A limited number of slots are available for each workshop to improve the experience and value for attendees, so mark your calendar and register early to secure your spot!

Wild Pig Management and Research Techniques

Organizers: David Keiter, University of Georgia, Savannah River Ecology Laboratory, Aiken, SC; Michael Cherry, University of Georgia, Jones Ecological Research Center, Newton, GA; James Beasley, University of Georgia, Savannah River Ecology Laboratory, Aiken, SC; Michael Conner, University of Georgia, Jones Ecological Research Center, Newton, GA

Supported by: TWS Wildlife Damage Management Working Group; the Berryman Institute

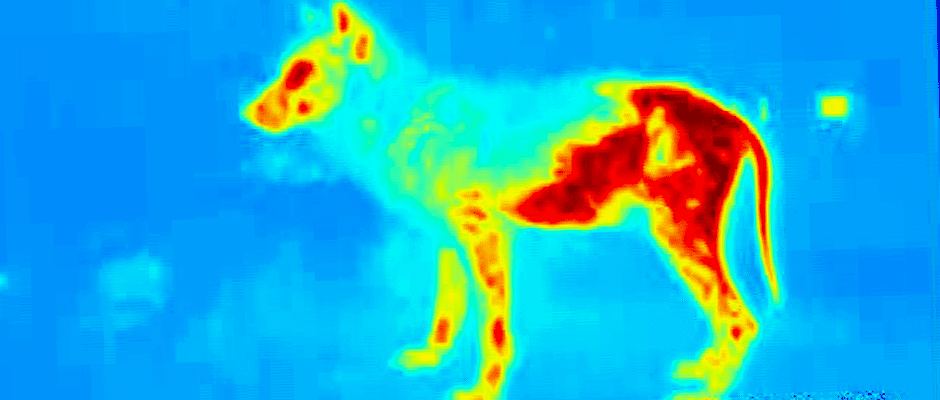

This workshop will include hands-on demonstrations of novel and established methods in management and research of wild pigs, demonstrations of different live-trap styles, thermal imaging and night vision technology, techniques for processing captured animals, and more. Attendees will also engage in group discussions of wild pig management, pig spatial ecology, disease surveillance research and management, use of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) in wild pig damage management, eradication efforts, and wild pig population ecology. This workshop is designed to help you prepare for working with wild pigs in areas where they are not yet established, and provide additional information and knowledge resources to those who are already involved in the management and research of these animals.

Modeling & Visualizing Wildlife Spatial Behaviors in 3D

Organizers: Jeff A. Tracey, U.S. Geological Survey, San Diego Field Station, Western Ecological Research Center, San Diego, CA; James K. Sheppard, San Diego Zoo Institute for Conservation Research, Escondido, CA

Supported by: Spatial Ecology & Telemetry Working Group

Advances in biotelemetry biologgers are enabling the collection of bigger and more accurate data on the movements of free-ranging wildlife in space and time. However, current estimators fail to capitalize on the 3D profiles offered by modern GPS biotelemetry datasets. This workshop will teach important concepts and skills to facilitate the analysis, modeling and visualization of wildlife space use in 3D, alternating between lecture content and hands-on exercises using case studies. The skills-based component of the workshop will focus on use of the mkde package for R, taking users through typical workflows including importing x,y,z biotelemetry location data and bounding layers, visualization and animation of 3D home range volumes, interpretation of results, and exporting into various formats for further analyses.

Sustaining Green Infrastructure in the City of Oaks

Organizers: Chris Moorman, North Carolina State University; George Hess, North Carolina State University; Nils Peterson, North Carolina State University

Supported by: Urban Wildlife Working Group

Raleigh, the capital of North Carolina, is known as the “City of Oaks” for its many oak trees which line the streets in the heart of the city. It is one of the fastest-growing cities in the country with a municipal population just under a half million people within a county of more than one million. The combination of a rapidly expanding urban matrix and the desire to maintain the green character of the city make Raleigh a perfect case study of the opportunities and challenges associated with urban wildlife conservation. This workshop will be entirely in the field and will include stops featuring:

- Local greenways to discuss research-based design strategies to conserve wildlife habitat

- A local natural area to learn about the WakeNatures Preserve Partnership to conserve high quality greenspace

- A conversation with Robin Moore about the Natural Learning Initiative to connect kids to the natural world at a park Robin designed for that purpose

- A demonstration of management practices to promote American woodcock and chimney swift conservation in the city

- A tour of a 300-acre forest where prescribed fire and timber harvests are used adjacent to highly developed areas that include the home of Carolina Hurricanes professional hockey team

- Hands-on activities using camera traps to explore urban wildlife ecology

Forestry 101 for Wildlife Biologists and Managers

Organizers: Andrew Crosby, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI; Blake Murden, Port Blakely Companies, Tumwater, WA; Fill Witt, University of Michigan-Flint, Flint, MI

Supported by: TWS Forestry and Wildlife Working Group

Timber management has a big impact on wildlife habitat, and offers one of our most powerful tools for manipulating habitat to meet specific wildlife management objectives. Though this workshop, we will provide wildlife biologists with the basic tools they need to understand forest management decision-making and help them communicate with foresters to ensure that both wildlife habitat and timber production goals are met.

The objectives of this workshop, which will be taught as a series of classroom lectures in the morning and hands-on practice at the Duke Forest during the afternoon, include providing you with:

- An understanding of forestry principles and common silvicultural practices

- A basic working knowledge of how foresters measure and describe forests

- Familiarity with standard forestry objectives and terminology

- Knowledge of the use of silviculture as applied forest ecology in wildlife management

Development of a Student/Professional Mentoring Program

Organizers: Susan P. Rupp, Enviroscapes Ecological Consulting, LLC, Springdale, AR; Kristi Confortin, Ball State University, Department of Biology, Muncie, IN; Paige Schmidt, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Tulsa, OK; Diana Doan-Crider, Animo Partnership in Natural Resources, Texas A&M University, Medina, TX; Maggi Sliwinski, University of Nebraska, Lincoln, NE; Larkin Powell, University of Nebraska, Lincoln, NE; Misty Sumner, Texas Parks and Wildlife Dept., Van Horn, TX

There is concern within the wildlife profession about the potential disconnect between what students are learning in academia versus what skills are needed by professionals within the workforce (Scalet 2007, Parker et al. 2008, Rupp 2012). Formalized mentoring can provide career development and psychosocial skills, recruitment opportunities, and information transfer while providing personal satisfaction for both the mentor and mentee (Wells et al. 2005).

In this workshop, we will use a case study from South Dakota and results from an online TWS membership survey to generate discussion about how a larger student-professional mentoring program across TWS may be developed nationwide. With engagement from participants, the workshop will:

- Provide a background on student-professional mentoring through presentations and discussion of survey results

- Provide a forum for discussion about how to best engage students and professionals

- Compare and contrast potential logistical obstacles at state versus national scales

- Identify potential solutions

- Produce a model for possible implementation by TWS in 2017

An Introduction to Spatial Capture-Recapture

Organizers: J. Andrew Royle, USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, Laurel, MD; Chris Sutherland, Department of Environmental Conservation, UMASS-Amherst, Amherst, MA; Richard B. Chandler, Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources, University of Georgia

Supported by: Biometrics Working Group

This workshop will be based around the book by Royle, Chandler, Sollmann and Gardner (2014) “Spatial Capture-Recapture” which participants will receive. Topics that will be covered include fitting spatially equivalent versions of standard capture-recapture models (M0, Mb, Mt), fitting models of landscape connectivity and spatial variation in density, multi-session and sex-structured models, and models that use samples with partial or no identity (mark-resight models, integrated models, and related).