Share this article

Wildlife Featured in this article

- Lesser sandhill crane

- Greater sandhill crane

WSB: Photographs can help track sandhill harvest trends

Wildlife managers developed a new tool to help track population data in game birds

Wildlife managers are developing photographic methods to track sandhill crane population changes across their range, which can be useful in informing hunting regulations.

Managers sometimes track harvest data and trends for game bird species by analyzing bird wings and parts that hunters sometimes mail into the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Wildlife managers then classify them by age, sex and species where possible, to determine any long-term shifts in populations.

Sandhill crane (Antigone canadensis) harvest is legal in North Dakota, as in many other states. But the tall, gawky birds’ large wingspans and spindly legs make their parts impractical to collect for wildlife managers. The most feasible way to determine subspecies and age would be to measure the length of their leg bones and part of their bill—from the back of their nostril to the tip of their beak.

As a result, wildlife managers have never really had a good way of tracking the age and subspecies trends of birds across their range.

“Right now, we just don’t have that information,” said Andrew Dinges, a supervisor in the private lands section of the North Dakota Game and Fish Department.

Photographic evidence

Dinges, who was a migratory game bird biologist at the time, wanted to see if newer technology might provide a better way to assess any changes in the midcontinent sandhill crane population that migrates through North Dakota. This information could protect sandhill cranes when they’re vulnerable, while also offering more hunting opportunities when the birds are abundant.

He turned to photography, since most hunters carry smart phones—a much cheaper and more practical option than sending bulky parts through the mail. He led a study on his findings, published recently in the Wildlife Society Bulletin.

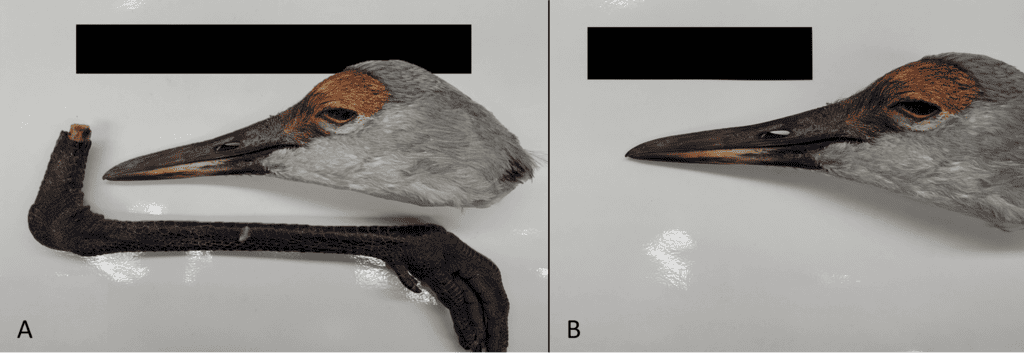

Starting in 2019, Dinges asked volunteers to mail him crane legs and bills. In the lab, he developed a way to accurately measure the size of parts of the bill and legs by taking photos of them next to an object of known length. Using computer software, he could digitally measure these parts to predict the age and subspecies of sandhill cranes, which are divided into lesser (A. c. canadensis) and greater sandhill cranes (A. c. tabida).

Using a measure of the actual bird parts and a measure of the parts in photographs that he took, Dinges developed correction formulas for predicting actual part length based on photos.

In the second phase of his research, Dinges mailed a block of wood of known length to participants along with instructions on how to upload the photos they took to a database. Participants were told to take photos of the crane parts with the block next to it for reference. He wanted to test if hunters were capable of taking photographs that could be used to digitally measure parts.

While conducting his research, Dinges found it was more difficult for hunters to take accurate photos of legs due to the difficulty of laying out those parts needed for measurement. This caused a drawback in terms of accuracy—to best determine whether a given crane is a lesser or greater sandhill, the leg bone measurement increases the accuracy of subspecies prediction.

For ease of use, he decided that only focusing on the beak and head would probably ensure better participation and data gathering. “Hunters were more likely to participate with that collection method,” Dinges said.

Dinges said that it’s still possible to estimate the subspecies by just using bill measurements, though it isn’t as accurate as if you obtained the measurement of parts of the leg as well. Still, Dinges said this information can help wildlife managers throughout the central flyway. For example, western North Dakota has higher daily bag limits for hunters since the majority of these birds are lesser sandhill cranes in that area. In the east of the state, there is a lower daily bag limit since greater sandhill cranes frequent this area more.

“If we had subspecies information, you could really start to fine-tune that line in North Dakota,” Dinges said about the geographical divide between lesser and greater sandhill cranes.

He hopes that state and federal agencies can employ this new technique to help track changes in sandhill crane populations. But since it’s a migratory bird, he said it will be important for the different states and Canadian provinces in the flyway to collaborate to get a more accurate picture.

This article features research that was published in a TWS peer-reviewed journal. Individual online access to all TWS journal articles is a benefit of membership. Join TWS now to read the latest in wildlife research.

Header Image: Developing a way to track population trends of sandhill cranes proved difficult in the past. Credit: Becky Matsubara