Share this article

Wildlife Vocalizations: Sara Gagné

Childhood salamander hunts led Gagné to pursue a career as an urban ecologist

Wildlife Vocalizations is a collection of short personal perspectives from people in the field of wildlife sciences.

On summer Saturdays when I was a kid, my father would take me to the Morgan Arboretum near our house on the Island of Montreal to look for salamanders. With nets and jars in tow, we would head down to an old rock quarry surrounded by maples, hemlock and beech.

The quarry had been cut into the side of a small hill, leaving a sheer granite wall overlooking a shallow depression that filled with water in the spring. In the quarry pond, teemed the most mysterious and amazing creatures I had ever seen. Large, green tadpoles with two pairs of legs scattered as I waded into the water. Much smaller, deep-black American toad (Anaxyrus americanus) tadpoles swarmed in the sunshine, like a flock of starlings in the fall. Eastern newts (Notophthalmus viridescens) hung just below the water’s surface, legs dangling and flat, with keeled tails slowly moving from side to side. But best of all, blue-spotted salamanders (Ambystoma laterale), their dark, shiny bodies mottled electric blue, swam in the deep, ending up in my net—only if I was very lucky that day.

It was these salamander pursuits that started me on the path to becoming the urban ecologist and associate professor I am today—and to publishing my first book,” Nature at Your Door: Connecting to the Wild and Green in the Urban and Suburban Landscape.”

To my young eyes, the strange and beautiful creatures I encountered in the quarry pond were ambassadors of a world so full of intriguing permutations and possibilities that it baffled my imagination. Here were animals that, in a single lifetime, swam and breathed like fish underwater and walked and breathed like me on land. They could even breathe through their skin, and some did so all the time because they lacked lungs. Some, like adult newts, could pick and choose their lifestyle, remaining fully aquatic from egg to adult, or moving from the water to land and back again twice over depending on local conditions. To top it all off, we now know that salamanders fluoresce green in blue light—I won’t even speculate on my childhood reaction to a quarry pond filled with fluorescent salamanders—and can regrow severed limbs, and regenerate parts of their brains and spinal cords.

It astounded me that the seemingly super-powered creatures I encountered on these trips with my father lived such very different lives from my own, and, more so, that these incredible animals inhabited the same bustling Island of Montreal that I and approximately 1.8 million other people called home. While blue-spotted salamanders were busily traveling to and from breeding ponds, I was riding to and from school, until that point oblivious to their existence. The glimpse I got at the quarry pond of frogs, toads, newts and salamanders in all their glory awakened my mind to the myriad nonhuman lives being lived all around me. The world beyond my doorstep instantly became much more complex, beautiful and interesting, and one which now held countless fascinating secrets waiting to be discovered.

Learn more about Wildlife Vocalizations, and read other contributions.

Submit your story for Wildlife Vocalizations or nominate your peers and colleagues to encourage them to share their story.

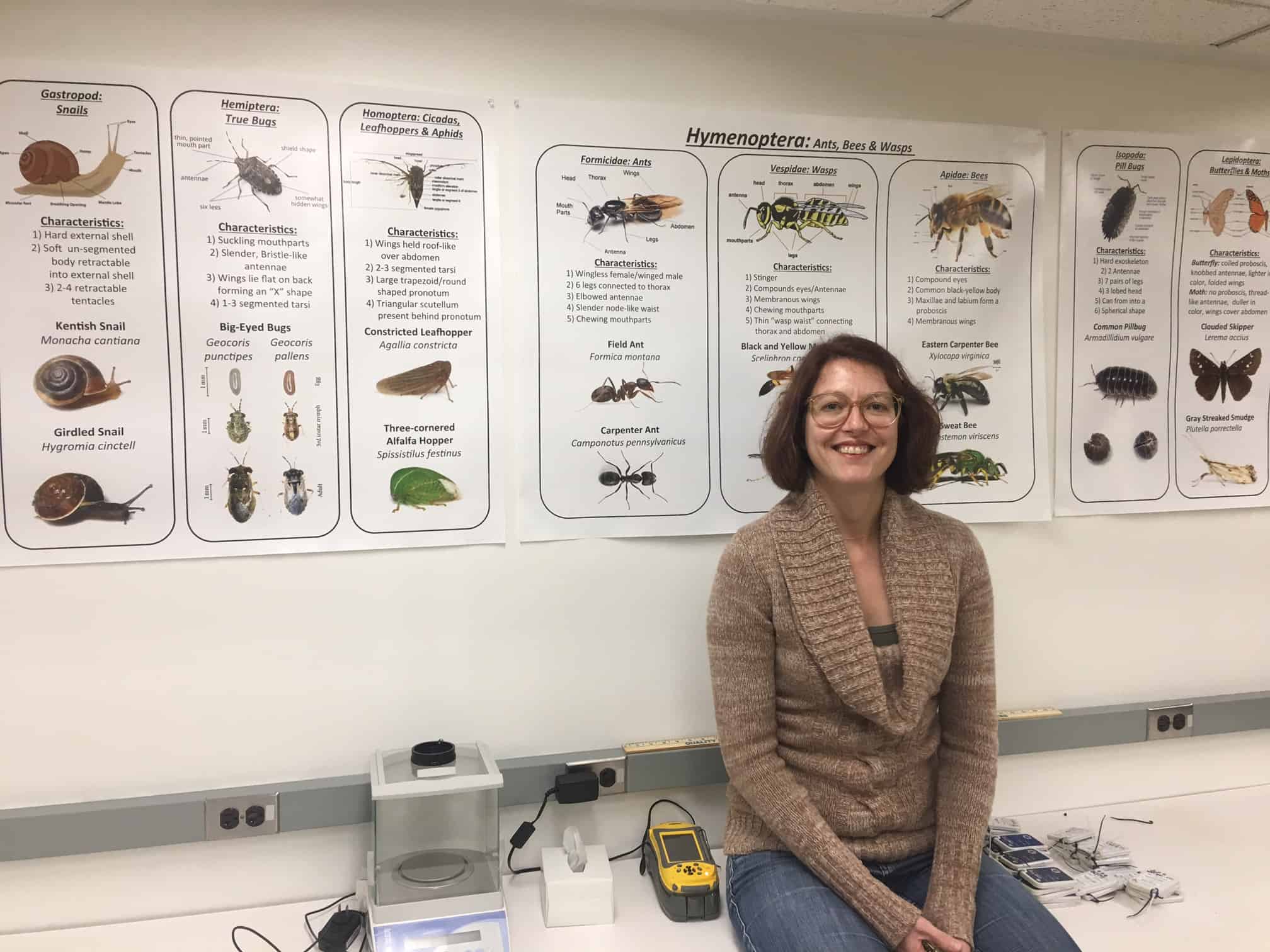

Header Image: Sara Gagné in her lab in 2017 where she and her students identify invertebrates collected in urban landscapes. Credit: Mary Newsom