Researchers know that climate change is causing turtles to produce more females, but for some turtles, it may also cause them to produce more eggs.

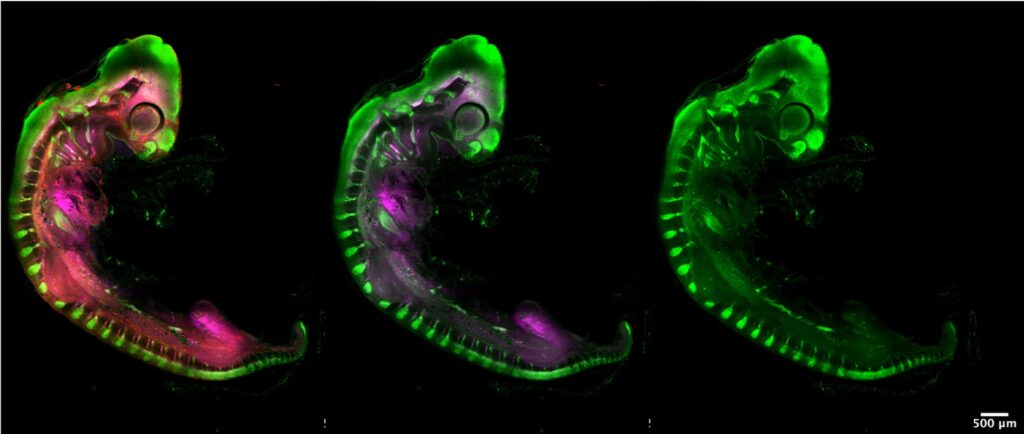

In a recent study published in the Journal of Current Biology, researchers analyzed red-eared slider (Trachemys scripta) eggs under different incubation temperatures to see how the increase in temperature affects the reproductive potential of females.

The team found that there was an increase in the number of germ cells—a type of cell that provides embryos with the future ability to produce sperm or egg—under warmer temperatures. With higher temperatures leading to more female hatchlings, and rising germ cell counts increasing the females’ egg capacity, turtle population dynamics may move into uncharted waters.

Producing more eggs “improves female reproductive potential and provides an adaptive advantage,” researchers suggest.

This is especially important as the warming climate skews many turtle species’ sex ratios, raising questions about their future reproduction. Turtle hatchling sex is determined by temperature, and warming trends are resulting in more females in many species. A study in 2018, for example, found that 99% of new green sea turtles (Chelonia mydas) hatched in Australia were females. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has classified rising sand temperatures as a threat to leatherback sea turtles (Dermochelys coriacea) due to these conditions producing more female hatchlings.

Red-eared sliders are also producing more female hatchlings than males, but an ability to produce more eggs overall could offer benefits to the population, researchers found.

Past research focused on temperature effects on gonadal sex determination, but not on germ cells specifically, said Boris Tezak, a postdoctoral researcher at Duke University and lead researcher of the study. While having a skewed sex ratio is a conservation challenge, he said, having more female turtles than males is less of an obstacle than the opposite. Increasing the reproductive fitness of females may even be a positive thing for the endangered species, which faces other challenges linked with the climate crisis, such as habitat loss and shifting nesting seasons.

Tezak stressed the importance of long-term studies on this topic given the long lives of turtles and the slow pace of sexual maturation in some species. It will take generations of turtles to truly see how increasingly high temperatures affect the reproductive fitness and longevity of turtle species globally.

“If we have a better understanding of the molecular mechanism behind sex determination, then we can better predict how changes in climate and temperature will affect sex ratios going forward,” he said.

Article by Tom Klein, AWB®