Drones provide a cost-effective, minimally invasive way for researchers to study threatened marsh deer populations and their habitat.

Marsh deer (Blastocerus dichotomus) are the largest cervid species in the Neotropics and occupy wetlands, savannas and grasslands in South America. In the Pantanal wetland in Brazil, these deer face a number of issues, including habitat reduction and fragmentation due to agriculture, cattle ranching and hydroelectric dams. Their populations have also been hit by illegal hunting, and they have also historically been vulnerable to diseases from livestock.

These challenges inspired Ismael Brack, a doctoral researcher at the Federal University of the Rio Grande do Sul in Brazil at the time, and his colleagues to use fixed-wing drones to estimate the deer’s abundance and their preferred habitat in a study published in 2023.

Taking flight in the wetland

The Pantanal Wetland is the world’s largest tropical floodplain. It has a seasonal rainy climate and receives periodic flooding from nearby rivers. Brack and his team’s study area, the Sesc Pantanal Private Reserve, covers 108,000 hectares and is characterized by a tropical savanna climate and an average rainfall of 1,200 millimeters.

The researchers conducted the study during the wetland’s dry season in September and October, where rainfall wouldn’t pose a challenge. But the dense, wet tropical landscape still makes traditional wildlife counts difficult, making drones the ideal tool.

“I have been working with drones for some years,” Brack said, adding that he has used them to detect species before. “That’s a nice thing with this study. We’re really applying this approach for an ecological problem.”

While drones are fairly common, Brack said that using them for science can be somewhat challenging, especially when navigating proper licensure for drone flights.

“I think it’s a tool with great potential to survey wildlife species,” he said. “The challenges are implementing methods that give you the most reliable information, and there are many legal restrictions that are tough to deal with.”

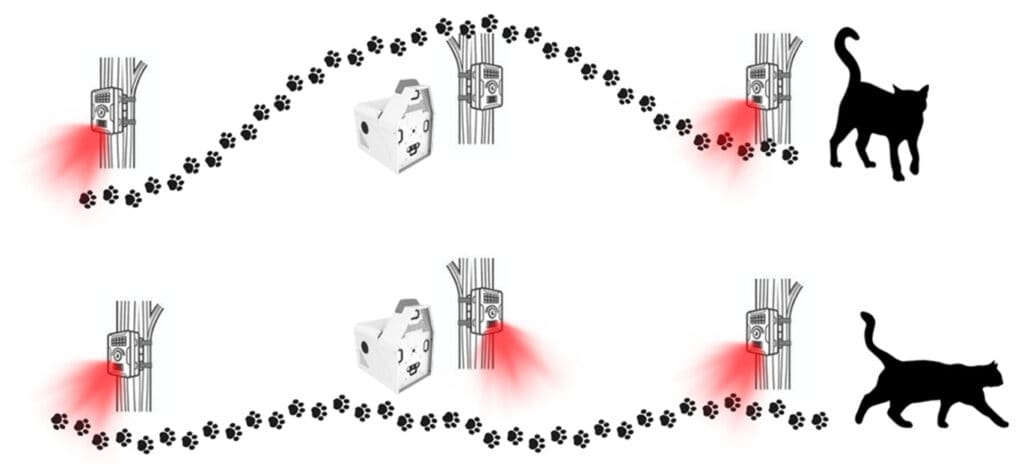

Each flight took the team just over an hour. The researchers conducted the flights during the coolest hours of the day when deer are most active, and they made sure the drones avoided highly forested areas marsh deer don’t tend to use. In total, the researchers operated 25 flights, collecting 25,000 images.

Counting marsh deer

Researchers reviewed the thousands of images to ensure accuracy. They carefully examined the images while marking each marsh deer found with special software.

Over the course of two-month study, the team counted 66 marsh deer. While this may not seem like a large number, the flights and photographs provided valuable insight into the deer’s habitat. Identifying these high-quality areas for marsh deer can improve conservation planning actions, like designating protected areas or mapping firefighting priorities during wildfires.

The researchers found marsh deer preferred areas with significant green vegetation that were closer to bodies of water. However, the team also discovered that this habitat overlaps with that of predators, specifically jaguars, during the dry season. The risk of predation, though, did not deter the marsh deer from these areas.

Future research

In 2020, the Pantanal was severely impacted by wildfire. As a result, Brack believes that using drones will allow researchers to better understand the effects of these fires on the Pantanal flora and fauna.

“Understanding the factors that really affect the abundance of the species was the first step,” Brack said. “But now, we’ve been trying to monitor the species in the same reserve with the same methods. We had these huge megafires in 2020 that impacted more than 90% of the reserve, so we are trying to use the same methodology to really see the impacts.”