Share this article

Wildlife Featured in this article

- wood frog

Chemicals from oil sands could hinder frog development

Frogs experience developmental abnormalities and decreased survival

The chemical byproducts of oil sands mining in Canada could affect the growth and development of amphibians.

Canada’s oil sands, which have been sitting in northern Alberta for eons, are one of the largest deposits of crude oil in the world. Separating that dense oil, known as bitumen, from the sands requires using an enormous amount of water. The water gets polluted in the process and is stored in massive reservoirs known as tailings ponds.

Chloe Robinson, a researcher at Queen’s University in Ontario, said there may be 1.5 trillion liters of wastewater held in these reservoirs. That’s enough to fill half a million Olympic-sized swimming pools, which if placed end to end, would stretch from Toronto, Canada to Sydney, Australia and back.

These tailings ponds contain a number of harmful chemicals. But perhaps one of the most toxic are naphthenic acids and their associated compounds. Growing evidence suggests water with these chemicals may be leaking into groundwater.

“Unfortunately, these tailings ponds don’t really offer a sustainable method of managing or storing this water,” Robinson said.

There is growing pressure on the industry to treat this water and release it into the Athabasca River, especially as new treatment technology is developed. But it’s unclear whether this can be done safely. Before the government sets guidelines on acceptable levels of these chemicals, researchers need to better understand the effects they have.

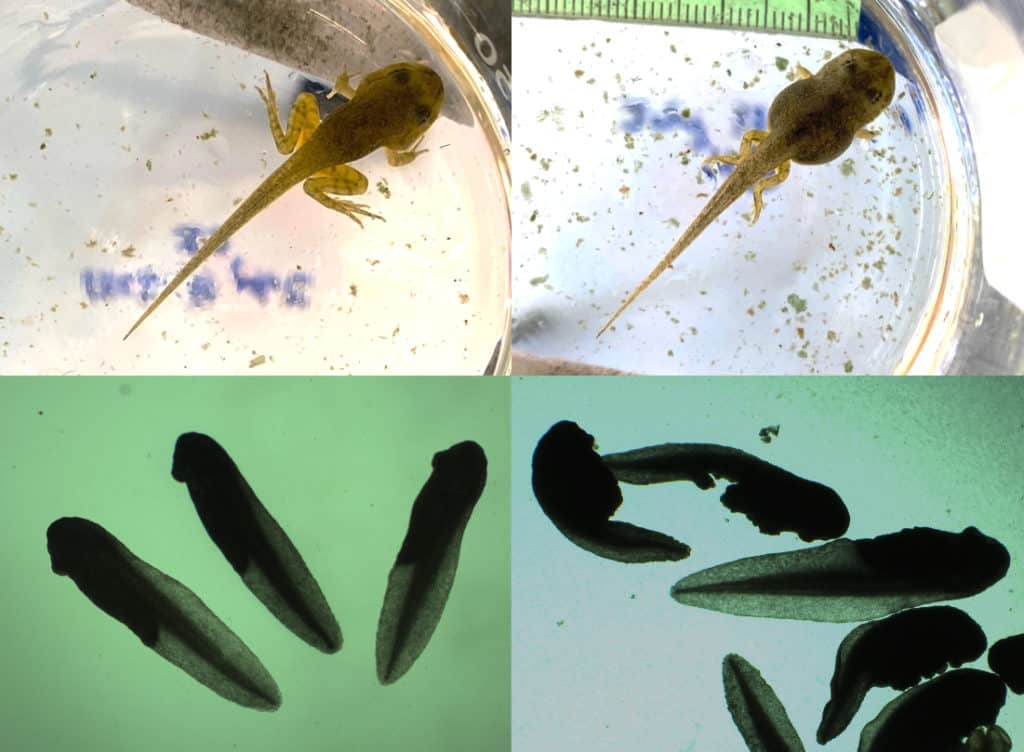

In a recent study published recently in Environmental Pollution, Robinson, her supervisor Diane Orihel, an ecotoxicology professor at Queen’s, and their co-authors tested the effects of naphthenic acids on wood frogs (Rana sylvatica). This species isn’t endangered, but in general, amphibians are vulnerable to water quality issues as they breed and spend at least their early lives in water.

“They are the freshwater equivalent to a canary in a coal mine,” Robinson said.

The research team captured wild wood frogs, and released them into water with naphthenic acids at the Queen’s University Biological Station north of Kingston, Ontario in the spring of 2021. These were released in tanks with two concentrations—five milligrams per liter and 10 milligrams per liter. They also had a control group not exposed to the acids.

In the tanks, they observed frog breeding, egg laying, and monitored the growth of the tadpoles that subsequently hatched for the next few months.

Developing problems

The team found that naphthenic acids didn’t affect the mating behavior or fertility of adult frogs. But the tadpoles raised in water with the higher concentration of naphthenic acids showed a number of growth and survival impacts. These concentrations are similar to that found in some reclaimed wetlands, as well as wetlands affected by the oil sands industry. They don’t approach the concentration of the acids in the tailings ponds themselves, which can be up to roughly 80 milligrams per liter.

These frogs had reduced survival up to metamorphosis, and lower growth rates compared to the control group and to the group exposed to lower concentrations of naphthenic acids.

The problems didn’t stop there. Frogs exposed to high concentrations of the acids also had more frequent developmental abnormalities. These included smaller limbs at metamorphosis and even missing toes.

These abnormalities could present obstacles to frog fitness, though the researchers didn’t test for that in this study. “That could affect their foraging success and their ability to escape predators,” Robinson said. Development issues and higher predation could lead to a decrease in frog populations in regions affected by oil sands wastewater.

“As a whole, amphibians are some of the most endangered animals in the world and in Canada.”

Chloe Robinson

The researchers used wood frogs in this experiment, since they are a common species in the Athabasca oil sands region of Alberta. But they are also explosive breeders, Robinson said. This means that populations breed in wetlands over a relatively short period.

“Other frogs spend more time in aquatic environments in comparison and may have different responses to naphthenic acid pollution,” Robinson said. “As a whole, amphibians are some of the most endangered animals in the world and in Canada.”

Due to the risks that it presents to amphibians and potentially other wildlife and humans, Orihel said that treating the wastewater is a better option than keeping it in tailings ponds, which run the risk of breaching.

“Decision makers need evidence for what is safe, and what is not,” she said. “This is why we do our work.”

Header Image: Wood frogs were captured from the wild for an experiment analyzing their exposure to oil sands chemicals. Credit: Chloe Robinson