Share this article

Wildlife Vocalizations: Andrea Miranda Paez

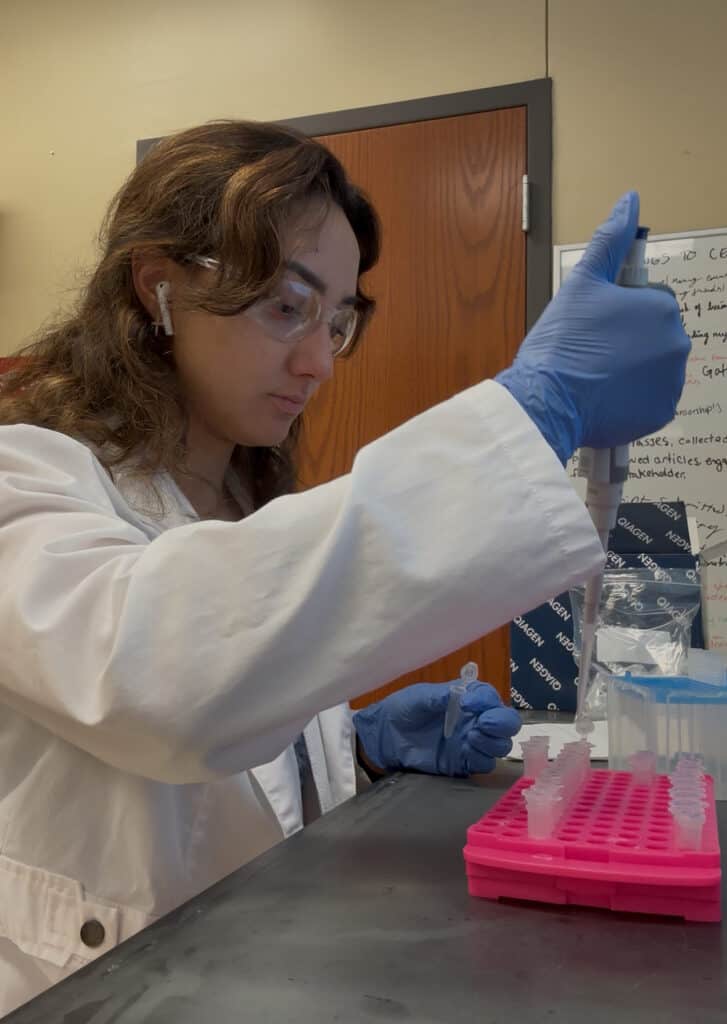

PhD candidate shares how she went from a rich Hispanic culture in Laredo, Texas to working with Alaskan wildlife

I grew up in Laredo, Texas, surrounded by the richness of Hispanic culture, whose habits and lessons still echo in everything I do. One of my favorite sayings I learned growing up is “Al mal tiempo, buena cara,” which translates to “In bad times, put on a good face.” It was more than just advice; it was a lesson in resilience, optimism and determination. I’ve carried that phrase through my undergraduate years at Texas A&M University, especially when I decided to study wildlife science, a major I hadn’t heard of growing up, since careers like medicine, law or engineering were often seen as the secure, respectable paths in my community. Choosing a career in wildlife sciences came with fear and uncertainty, but with the unwavering support of my parents and loved ones, I leaped. That same saying, “Al mal tiempo, buena cara,” reminded me to face challenges with courage and to take pride in doing my best, no matter the obstacles.

That mindset has shaped my approach to research and fieldwork. In my doctoral research at Auburn University, I study the population genetics of Alaska’s Mulchatna caribou (Rangifer tarandus) herd to understand how genetic diversity and metapopulation structure shape their management. I analyze raccoon (Procyon lotor) genetic data in Alabama and use that as a proxy for how rabies may spread across the state. I also survey wildlife professionals to better understand how genetic tools are being perceived and applied in conservation decision-making. Graduate school has given me opportunities I never imagined, from conducting genetic analyses that can help inform conservation to collaborating with state and federal agencies. But the most memorable field experience was in the summer of 2022, when I worked as a fish and wildlife technician for the Alaska Department of Fish and Game in Palmer, Alaska.

That season tested me physically, mentally and emotionally. I experienced my first small airplane flights and helicopter rides, radio-tracking caribou from the air. I learned how to jump out into deep snow to search for calf collars, sometimes climbing steep mountains with a shovel in hand while making sure not to slip. I saw grizzly bears (Ursus arctos horribilis) from the helicopter as we flew between Dillingham and Bethel, and below us stretched a breathtaking mosaic of snow-capped mountains, winding rivers, wide valleys and glacial expanses. In those moments, I felt both awe and respect for the wildness of Alaska. The work was exhausting, and I discovered that spending hours in small planes and helicopters often left me motion sick. Dramamine, the medication I used to ease the motion sickness, made me so drowsy that I had to find other ways to push through, turning each flight into both a physical and mental test. Still, I held tightly to my Latin roots and made sure not to take a single moment for granted. Every challenge became a chance to learn and grow.

That summer also opened my eyes to the people who live in Alaska’s remote communities. Many rely on snowmobiles, ATVs and small aircraft to move between places, and their knowledge of the land is invaluable for conserving species like caribou. I realized conservation isn’t only about data or biology but also about listening to and working alongside the people whose lives are most connected to these ecosystems we study. Later that season, I also had the opportunity to help out in a bear genetics study. I hiked rugged trails in Denali State Park carrying a gallon of pig blood to set barbed-wire DNA traps, nervous about being in bear country for the first time and battling the mosquitoes. But once again, I leaned on resilience and optimism. By the end of the project, I had gained confidence, respect for the fieldwork side of wildlife biology, and a new appreciation for how it complements the computer-based analyses I conduct in my PhD.

Beyond the science, I was also struck by how culture travels and adapts in new landscapes. One of my most unexpected joys in Alaska was sitting down to a delicious halibut taco at a small Mexican restaurant, a similar taste of home, but thousands of miles away. It reminded me that just as people from our communities have built lives in distant places, so too has our culture taken root, blending with local traditions in unique ways. In many ways, it mirrored what I was witnessing all around me. Just as culture finds new roots far from home, wildlife is woven into every aspect of life in Alaska, from the caribou herds to the grizzlies that roam southwest Alaska and the salmon that sustains communities. Both culture and wildlife, I realized, carry stories of resilience, movement and connection across landscapes.

Over time, I’ve come to realize that visibility matters as much as the science itself. That is why I am passionate about science communication and why I serve in roles that create inclusive spaces, from managing my lab’s social media to contributing to the Alabama Chapter of The Wildlife Society’s outreach. Now I serve as social media chair for the Latin American and Caribbean Working Group of The Wildlife Society.

I want to help create the kind of space I wasn’t aware of when I first started college—one that reflects the richness, resilience and brilliance of our Latin communities. Today, I balance research, outreach and leadership with the belief that conservation is not just about protecting wildlife but also about honoring culture, heritage and community. My journey through wildlife science has been one of risk, growth and discovery. But through it all, I’ve carried the wisdom of my background and the strength of my Mexican culture.

Wildlife Vocalizations is a collection of short personal perspectives from people in the field of wildlife sciences. Learn more about Wildlife Vocalizations, and read other contributions.

Submit your story for Wildlife Vocalizations or nominate your peers and colleagues to encourage them to share their story.

For questions, please contact tws@wildlife.org.

Header Image: Andrea Miranda Paez during tracks radio-tracking collared caribou near Bethel, Alaska. Credit: Renae Sattler