Share this article

Wildlife Featured in this article

- spectacled caiman

- American alligator

- American crocodile

- three striped mud turtle

- banded eater snake

- Burmese python

- Argentine black and white tegus

Wild Cam: Targeting invasive caiman hatchlings helps with their population removal

Wildlife managers remove invasive reptiles from Everglades during 10-year project

Wildlife managers seeking to remove invasive caimans from the Everglades are finding success by rapidly responding to caiman sightings and persistently targeting the reptiles during hatching season.

This strategy allows them to catch newly born South American reptiles before they have a chance to grow.

“It’s a lot easier to remove the hatchlings because they are naïve and inexperienced,” said Sidney Godfrey, a wildlife biologist at the University of Florida.

Invade and spread

Spectacled caimans (Caiman crocodilus), native to many tropical countries in Latin America, were likely introduced primarily in and around the city of Homestead located in southern Florida during the 1950s. Godfrey speculates pet owners living in the Homestead Air Reserve Base may have released them.

Initially, wildlife biologists considered them feral because they didn’t think the caimans were doing well in their adopted home. But by the 1970s, not only were biologists finding juveniles, hatchlings and adults in the state, but the reptiles had also spread into wetlands bordering Biscayne Bay from the canal areas around the Homestead base where they were initially found.

In a study published recently in Management of Biological Invasions, Godfrey and his colleagues evaluated a decade’s worth of surveys and removal data to gauge caiman management success.

Caimans are often found in Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan projects, or areas that managers are restoring to more natural water systems. Some of these areas don’t have many native alligators (Alligator mississippiensis) or crocodiles (Crocodylus acutus). When the caimans move in, they grow to large numbers if they’re not controlled. Once the areas are saturated with the species, native crocodilians don’t have much space or resources to move in.

“We don’t seem to have many native crocodilians showing up when the caimans get to high enough densities,” Godfrey said.

During the course of the study, the researchers removed 251 caimans, necropsying many of them to determine if they could learn anything that would help with removal.

The necropsies revealed that the invasive reptiles are eating native wildlife species. They are generalists, so their stomach contents included amphibians, birds, mammals, crustaceans, fish and other reptiles like three striped mud turtles (Kinosternon baurii) and banded water snakes (Nerodia fasciata). The necropsies also revealed partly developed eggs, which helped the researchers calculate predicted hatching dates.

Removing the caimans from their habitats was sometimes tricky. The caimans would often hide at the bottom of the wetland when the researchers showed up, and Godrey had some close encounters with the reptiles. Spectacled caimans are smaller than alligators, but they can still reach a size of 4-5 feet long.

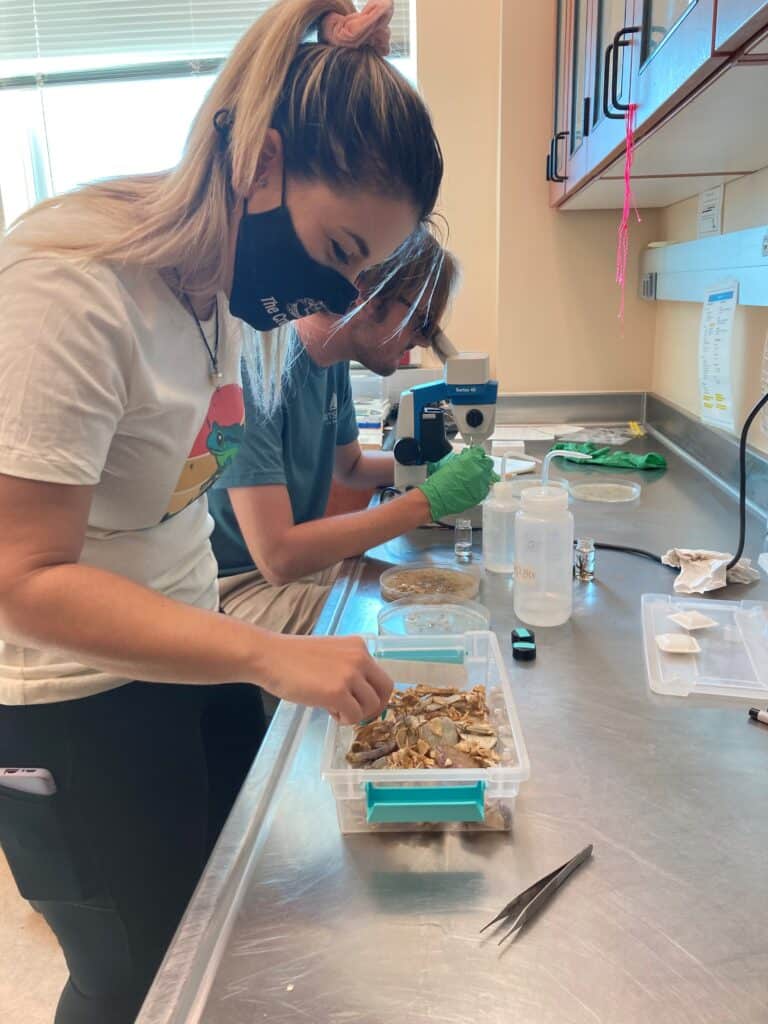

Juveniles were relatively easy to snare with poles and wire snares (which researcher Jake Edwards is using in the photo above). But the adults were trickier to capture, especially if people tried to catch them previously. One male repeatedly eluded the team, swimming safely to the other side of the pond whenever researchers were around. To catch it, the team had to go in at night. One team member would shine a light on it from far away, keeping its attention, while Godrey snuck up on it from behind with lights off. “We made it think that we weren’t going to do anything,” he said.

Seasonal targeting

The researchers determined that the best way to reduce the caiman population, in general, was to target them during nesting season. They first had to figure out exactly when this was—in the beginning they only had a six-week window to go by. But by the end of the decade, they had narrowed that down to a two-week period when most nests hosted hatchling caimans.

Caimans are generally difficult to detect, but night surveys, involving shining spotlights, can reveal a group of new hatchlings more easily, as their eyes reflect red in the lights. Since the newly hatched individuals tend to cluster together near the nest site, clutches like the one above, held by Godfrey, are relatively easy to find at night.

The researchers didn’t always strike immediately once they located hatchlings, though. They usually waited to see if they could find and remove the mother, which often hang around the newly hatched for a couple of weeks.

If they don’t catch the female, then they would just come back to roughly the same area the following year, since the females typically show some nest site fidelity.

“We don’t always get that adult female, but we usually get the hatchlings for that year,” Godfrey said.

Within the area covered by the Biscayne Bay survey route, this strategy has worked so well that the researchers believe there may only be a handful of adults left in the area, including a very elusive adult female. They haven’t actually seen the female, but have found hatchlings in the area.

Godfrey said the findings caution that traditional surveys may not always account for every animal. In the future, the research team plans to use tools like thermal cameras to see if they can find nests and destroy the eggs before they hatch. Trail cameras may also be useful for identifying elusive adults and detecting activity patterns.

He also said that while this technique seems to be working in their study area, it may not work as well in other areas. Some reports have identified caimans in far flung parts of the Everglades, perhaps a legacy of other invasions.

“We have to keep our foot on the gas,” Godfrey said in terms of continuing the removals. Just the same, their study shows a potential route to success, in some cases—a positive finding when compared to the difficult to manage invasions of other reptiles like Burmese pythons (Python bivittatus) and Argentine black and white tegus (Salvator merianae).

“We’ve definitely seen a big decline in encounter rates, which is encouraging when you consider that they have been established in these areas for decades.” he said.

The removals seem to help native crocodilians, albeit it with a “substantial time lag.” There have been some anecdotal observations of alligators returning after caimans were removed from an area much later.

This photo essay is part of an occasional series from The Wildlife Society featuring photos and video images of wildlife taken with camera traps and other equipment. Check out other entries in the series here. If you’re working on an interesting camera trap research project or one that has a series of good photos you’d like to share, email Josh at jlearn@wildlife.org.

Header Image: An adult spectacled caiman captured in the Biscayne Bay Coastal Wetlands, an Everglades restoration project. Credit: Nick Scobel