Share this article

Wild Cam: Remote cameras zoom in on population size

Researchers found camera traps can replace traditional methods to gauge mammal densities

For 50 years, biologists in Yukon have been measuring the ups and downs of snowshoe hare and Canada lynx populations the old-fashioned way. Trudging into the boreal forests of the Shakwak Trench each winter, they set traps to capture, tag and recapture the hares and estimate population densities based on what they find. For lynx, they head out by snowmobile and count the tracks they come across.

“I’ve been studying these things most of my life,” said Stan Boutin, emeritus professor at the University of Alberta, who started researching the relationship between these two intertwined species as a graduate student in 1977 and is still at it in his retirement.

The old method worked well for half a century. But in a new study led by Alice Kenney, of the Outpost Research Center, researchers asked if remote cameras—increasingly used in wildlife biology—might offer scientists an easier way to make estimates. If triggering a camera can tell them an animal is present, could the number of triggers tell them how dense the population is?

“It’s dead obvious—intuitively obvious,” said Boutin, a co-author on the study published in the Journal of Wildlife Management. But that didn’t mean it would work.

With 50 years of experience in the forests around Lhù’ààn Mânʼ—or Kluane Lake—Kenney and the team felt it would be the perfect place to see if camera traps could take the place of biologists on the ground. “We have detailed knowledge of that whole ecosystem,” Boutin said. “It was an excellent opportunity to compare camera traps to more tried-and-true methods.”

The team set up 72 remote cameras throughout the forest and gathered images over seven years to see if camera hit rates could allow them to accurately estimate population densities.

Canada lynx (Lynx canadensis) and snowshoe hare (Lepus americanus) go through roughly 10-year population cycles. When hare numbers rise, lynx numbers go up, too. When hares peak and fall, lynx numbers tumble after them. Biologists could see that pattern from Hudson Bay fur trade records going back into the 19th century. But before the 1970s, they didn’t know why it was happening.

“We figured out what’s mainly driving the cycle,” Boutin said. “It’s a pretty straightforward predator-prey relationship. But there are always sideline questions.”

This time, the sideline question was if camera traps could take the place of live traps. When the researchers compared their calculations based on camera hits to their estimates based on traditional methods, they found the cameras worked well—and they were cheaper, less time consuming and less invasive.

“It turns out it’s a very simple relationship,” Boutin said.

The method also worked to estimate coyote densities (Canis latrans). Red squirrels (Tamiasciurus hudsonicus), on the other hand, spent too much time in trees to appear on camera.

It could probably provide estimates for species around the world, Boutin said. That’s particularly important now as researchers try to track how climate change is affecting populations. Those efforts need long-term data, but 50-year studies like the Yukon project are rare.

“Not many studies have done that,” Boutin said. “Once cameras come into play and are tested further, there’s no reason we won’t have this sort of long-term data becoming more commonplace.”

This photo essay is part of an occasional series from The Wildlife Society featuring photos and video images of wildlife taken with camera traps and other equipment. Check out other entries in the series here. If you’re working on an interesting camera trap research project or one that has a series of good photos you’d like to share, email Josh at jlearn@wildlife.org.

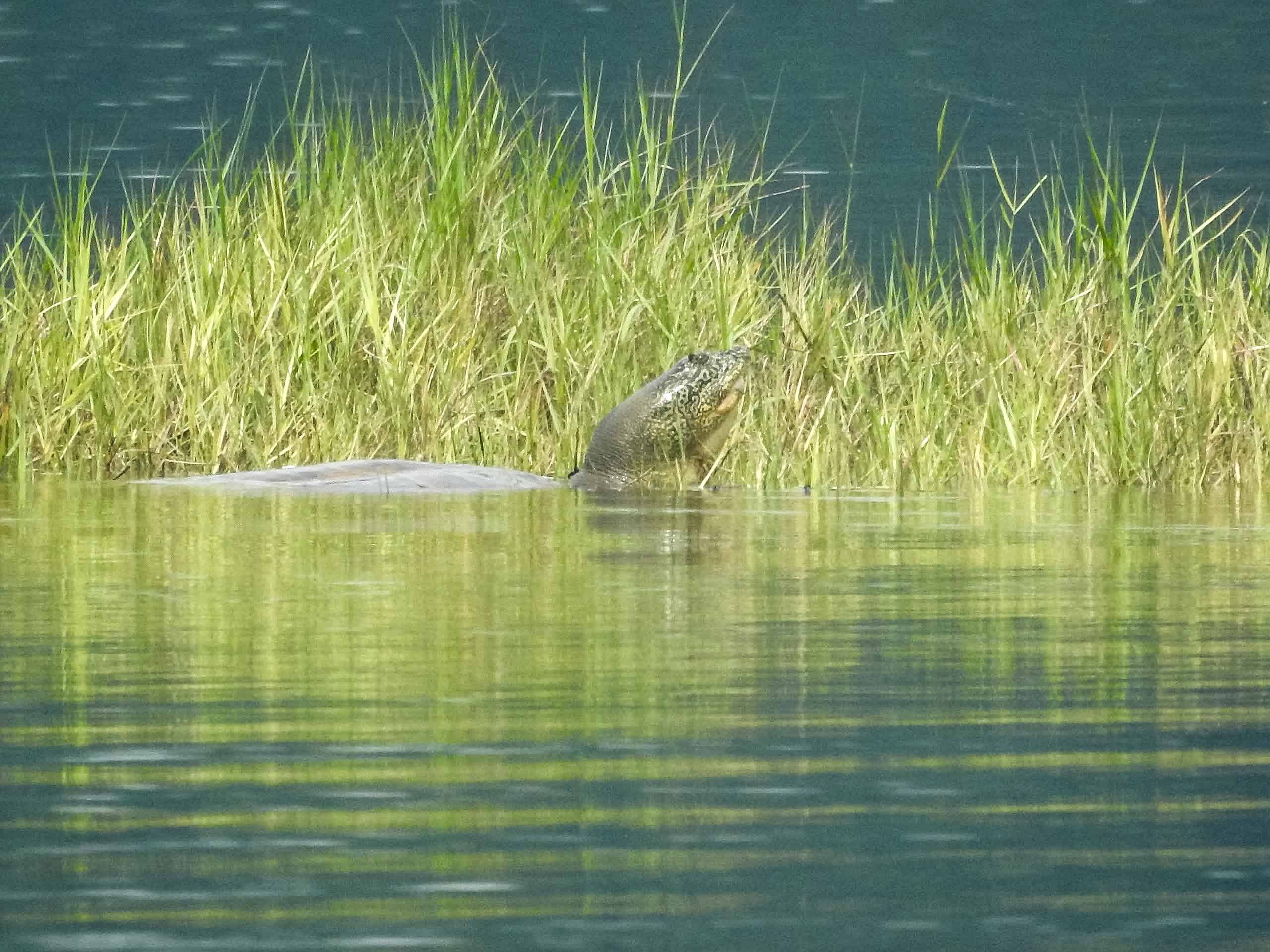

Header Image: A moose (Alces alces) inspects a remote camera set up to gauge wildlife populations in the Yukon. Credit: Alice Kenney