Dozens of rickety, old office cubicle-sized pens line up next to each in the U.S. Geological Survey’s Eastern Ecological Science Center at the Patuxent Research Refuge in Maryland. The ones sitting closest to a colorful, single-story old metal building adorned with mosaic tile work and an electric car covered in custom-made metal plate patterns appear relatively well-maintained. One of these pen sports a large tree blaring the sounds of 17-year cyclical cicadas common for the area in June 2021. Others nearby just hold grasses or a few waist-high plants and bushes.

Farther away from the small building and accompanying shipping containers, the pens are a little more decrepit, swallowed by overgrown vegetation. The pens are the remains of a gradually deteriorating wildlife conservation project in Maryland meant to help bring back North America’s tallest, federally endangered bird.

[aesop_image img=”https://wildlife.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Bee-lab-2-scaled.jpg” panorama=”off” credit=”Credit: Joshua Rapp Learn” align=”center” lightbox=”on” captionsrc=”custom” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”inplaceslow” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

“I’m super happy with a piece-of-junk building in an abandoned 30-acre impoundment full of invasive species,” said Sam Droege. A soft-spoken guy with long, greying hair worked partly into braids, Droege now manages the area that used to represent an important part of the original whooping crane (Grus americana) recovery plan started by the USGS in the mid-1960s. But funding dried up for this crane program, and it was eventually closed in 2018.

[aesop_image img=”https://wildlife.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/bee-lab-3-scaled.jpg” panorama=”off” credit=”Credit: Sam Droege” align=”center” lightbox=”on” captionsrc=”custom” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”inplaceslow” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

Facing funding problems of his own for his U.S. Geological Survey’s Native Bee Inventory and Monitoring Lab that then paid rent to the U.S. Department of Agriculture at their Beltsville Agricultural Research Center to use some of their nearby Patuxent Research Refuge, Droege moved his operation to what he saw as the ideal place to study bees in October 2018—right where the remaining federally endangered whooping cranes were still waiting for adoption.

“Nobody bothers me out here,” Droege said.

[aesop_video src=”youtube” id=”l8ewNuMkgwo” align=”center” disable_for_mobile=”on” loop=”on” controls=”on” mute=”off” autoplay=”off” viewstart=”off” viewend=”off” show_subtitles=”off” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

Caption: Sam Droege demonstrates how to capture bees. Credit: Joshua Rapp Learn

Little is known about bees beyond the well-studied western honeybees (Apis mellifera) and bumblebee species that pollinate so many of the fruits, vegetables and grains we eat. But there are an estimated 4,000 species of native bees found in the U.S., and many of them have yet to be described by scientists. That’s where Droege comes in. As if identifying these bees wasn’t a daunting enough task, he’s also trying to determine which plants these pollinators are most associated with.

“It’s a very young business right now, and we’re just doing the boring work,” Droege said.

[aesop_image img=”https://wildlife.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Bee-lab-4-scaled.jpg” panorama=”off” credit=”Credit: Erick Hernandez/USGS Bee Inventory and Monitoring Lab ” align=”center” lightbox=”on” captionsrc=”custom” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”inplaceslow” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

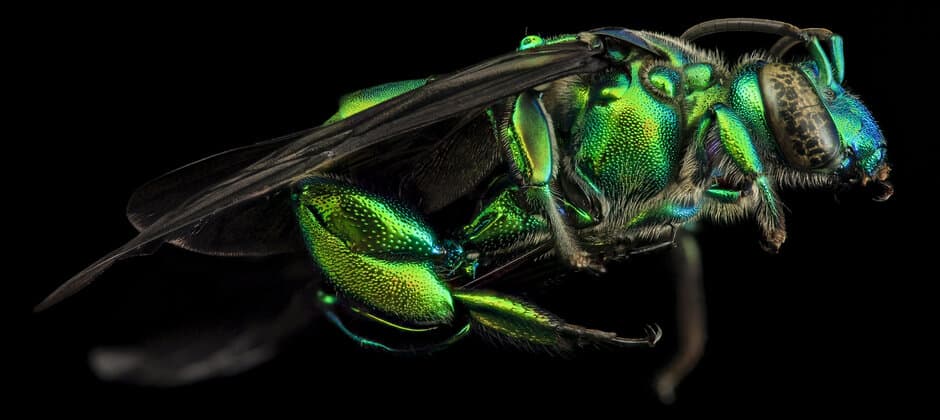

In 2016, Droege was still working at the Beltsville facility. He worked in a cramped office overflowing with framed cases of mounted bee specimens, pizza boxes full of mounted bee specimens, and random single bees and other curious insects of every sort preserved in every possible manner imaginable. In that office, he also had his bee photography studio, where he and his colleagues create detailed images, like the one above of a Cicindella purpurea, and upload them to the bee lab’s Flickr page. In the basement, he took the preserved specimens from jars of soapy water and dried them out in a clothes dryer for taxonomic identification.

The money was running short by 2017. “I’m going to get screwed here if I don’t do something,” he thought. Then, he found the old whooping crane facilities not too far away. He asked his superiors to give him the keys to that building, and he’d move in and fix the place up. “They were so desperate that they said ‘Yes.’”

[aesop_image img=”https://wildlife.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/bee-lab-5-scaled.jpg” panorama=”off” credit=”Credit: Joshua Rapp Learn” align=”center” lightbox=”on” captionsrc=”custom” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”inplaceslow” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

The place was a lot more run down when Droege first moved in. “The stench of mouse urine was everywhere,” he said. The area was nearly forgotten. It was in such bad condition that he could do whatever he wanted with the place. He gutted the main building, sawed his own timber to create a work shed, and fixed up some of the old facilities. Inside, he rehomed all of his pizza boxes and framed specimen trays, his macro photo study and other curiosities like a massive stuffed immature bald eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) that watches over the lab.

His partner, an artist working with recycled tiles, created mosaic work on the side of the colorful building, and Droege used local earth and lime plaster on some of the walls to create an earthier vibe. When the higher-ups finally visited Droege to try to put a stop to some of his building projects, it was already too late. “My safety officer was like ‘Oh my god, he’s putting mud on the walls!’”

[aesop_image img=”https://wildlife.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/bee-lab-6-scaled.jpg” panorama=”off” credit=”Credit: Joshua Rapp Learn” align=”center” lightbox=”on” captionsrc=”custom” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”inplaceslow” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

But Droege was more focused on the ecosystem outside the laboratory. Since the place had more or less been left to rot as the whooping crane program was shutting down, invasive plants like Japanese honeysuckle, bittersweet, and “horrible callery pear” that sometimes produces smells of rotten fish proliferated in the altered area. Droege has been working to remove these and reinstall native plants to improve bee diversity.

“Part of our mission—this is a self-imposed mission—is to encourage people to convert these horrible habitats into something more in line with pollinator habitat,” he said.

At the same time, he’s conducting surveys to see what kind of bees might be attracted to these invasive plants.

[aesop_image img=”https://wildlife.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/bee-lab-7-scaled.jpg” panorama=”off” credit=”Credit: Joshua Rapp Learn” align=”center” lightbox=”on” captionsrc=”custom” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”inplaceslow” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

One thing Droege didn’t touch in the area was the old crane pens—100 of them. He plans to use the infrastructure to grow different plots of pollinator plants where he’ll conduct a variety of possible experiments with the bees. For example, he may plant edamame beans or other species—one to a plot—then collect bees over time to better understand pollinator relationships.

Information he learns on relationships between native bee species and plants could be uploaded onto a public database, he said, which conservationists could use. Farmers could also use the information to improve the pollination of their crops.

[aesop_image img=”https://wildlife.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/bee-lab-8-scaled.jpg” panorama=”off” credit=”Credit: Joshua Rapp Learn” align=”center” lightbox=”on” captionsrc=”custom” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”inplaceslow” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

But identifying species can be challenging. Droege can’t always tell by eye what he’s looking at without magnifying it with his equipment. This can make it hard to track their abundance.

“Nobody knows how to ID these darn things,” he said.

[aesop_image img=”https://wildlife.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/bee-lab-9-scaled.jpg” panorama=”off” credit=”Credit: Joshua Rapp Learn” align=”center” lightbox=”on” captionsrc=”custom” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”inplaceslow” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

Still, in 2021, more than half a century after the first whooping cranes were housed in the area, native bees are the phoenix that rose from the ashes of the abandoned whooping crane program. Alongside the main building, Droege has also installed a series of uncommon native plants he’s monitoring to see what kind of relationships they have with native species like the bumblebees pictured above. He’s tinkering with different organizations of plants, both in species, height and density.

“It’s such a game changer to both have the ability to manipulate the landscape and develop an actual experimental component,” he said.

[aesop_image img=”https://wildlife.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/bee-lab-10-scaled.jpg” panorama=”off” credit=”Credit: Joshua Rapp Learn” align=”center” lightbox=”on” captionsrc=”custom” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”inplaceslow” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

Droege also uses a strict yearly mowing regimen in the area to encourage more bees. Despite all this work, he hasn’t yet discovered a previously unknown species in the immediate area.

“We tend not to collect in these areas that heavily,” he said, adding that they are still at the beginning of planting there.

[aesop_image img=”https://wildlife.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Bee-Lab-11-scaled.jpg” panorama=”off” credit=”Credit: Sam Droege” align=”center” lightbox=”on” captionsrc=”custom” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”inplaceslow” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

In the meantime, creating a bee paradise is still ongoing for Droege and the people he works with at the research center. He said that the decorations and style of the place hopefully helps to attract interns and other people that would want to work there. It seems to be working—he now has a second colleague for the first time in years.

“The last thing I want is some new building where I can’t touch anything,” he said.

But it’s the architecture of the flowering plants and cacti outside that he hopes will continue to attract the real guests of honor in greater numbers in years to come.

This photo essay is part of an occasional series from The Wildlife Society featuring photos and video images of wildlife taken with camera traps and other equipment. Check out other entries in the series here. If you’re working on an interesting camera trap research project or one that has a series of good photos you’d like to share, email Josh at jl****@******fe.org.

Article by Joshua Rapp Learn