Share this article

Wildlife Featured in this article

- black-footed ferret

- prairie dog

USFWS rule would expand area for ferret reintroduction

It would also increase flexibility for wildlife managers, and encourage greater cooperation between managers and landowners

The USFWS has mapped out a major habitat expansion for black-footed ferret reintroduction in a final rule.

This rule, which expands designated black-footed ferret habitat by 184%, will take effect Nov. Nov. 6, 2023.

The rule provides “ a framework for establishing and managing reintroduced populations of ferrets in this area that will allow for greater management flexibility and increased landowner cooperation,” wrote the USFWS wrote in its final rule notice.

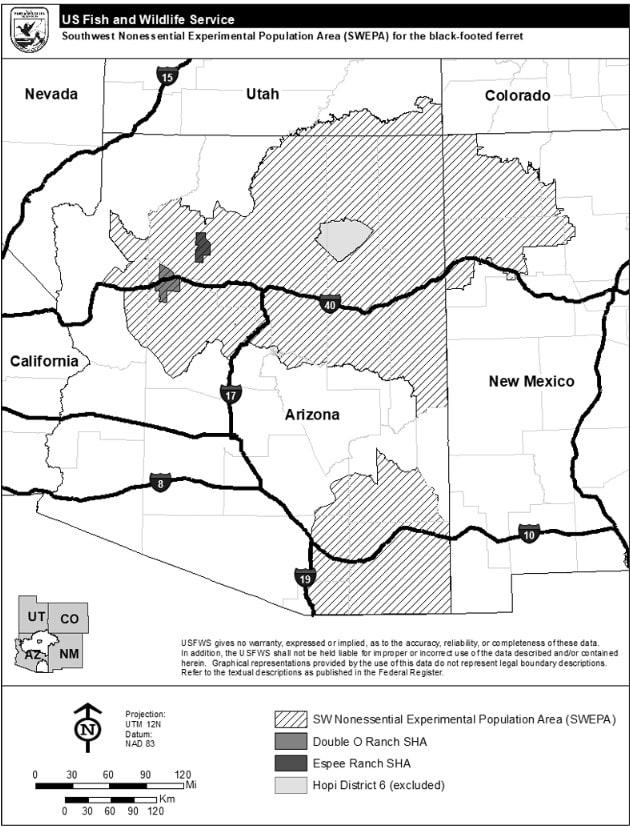

Deemed the “Southwest Experimental Population Area,” or SWEPA, spanning parts of Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah,” the area encompasses approximately 41 million acres.

That area includes the previously established Aubrey Valley Experimental Population Area, where black-footed ferret (Mustela nigripes) reintroduction has been managed since 1996 as part of a nonessential experimental population under section 10(j) of the Endangered Species Act.

Section 10(j) of the ESA allows the USFWS to designate a population of a listed species like the black-footed ferret as experimental to release into suitable natural habitat outside of its current range.

Experimental populations may be categorized as essential or nonessential. Nonessential experimental populations have loosened restrictions on take–to harass, harm, pursue, hunt, shoot, wound, kill, trap, capture or collect an animal–compared to other federally threatened and endangered species. When designated as a nonessential experimental population, incidental harm to black-footed ferrets is legal when resulting from traditional land uses and management, encouraging cooperation from private landowners.

The Wildlife Society encourages greater partnerships among state fish and wildlife agencies, Native American Tribes, local governments, private landowners and NGOs in carrying out complementary conservation efforts on private and other nonfederal lands to recover listed species and prevent the need to list additional species.

Black-footed ferrets were listed as endangered in 1967 under legislation passed before the ESA. They were grandfathered into the ESA in the 1970s, and approximately 350 exist in the wild today. The current population is the result of captive breeding efforts, originating from just seven breeding ferrets that were captured in 1985. The black-footed ferrets in the wild now are all descended from these seven ferrets, leaving the overall population with a severe lack of genetic diversity.

Black-footed ferrets primarily feed on prairie dogs and live within their colonies, making them heavily dependent on the health of prairie dog populations. Sylvatic plague, transmitted by fleas, is currently the greatest threat to prairie dogs and ferrets as it has an approximate 90% mortality rate and can completely collapse colonies leading to local extinctions. Pesticides to eliminate fleas and vaccination efforts of prairie dogs and ferrets have helped.

The Wildlife Society recently expressed support for increased appropriations for critical renovations to the USGS National Wildlife Health Center, which has been instrumental in the research and development of these vaccines.

Header Image: A wild black-footed ferret (Mustela nigripes) in Soapstone Prairie Natural Area, Colorado, a close site to the National Black-Footed Ferret Conservation Center. Credit: Tom Klein