Share this article

Sea turtle populations rise globally

Even as doom and gloom stories flood the news, conservation efforts are turning the tide for threatened sea turtles. New research suggests that all seven sea turtle species are experiencing population growth worldwide, demonstrating the ecological value of long-term conservation policy and action.

“What people have been doing all these years on sea turtles seems to have had a positive impact on their populations,” said Antonios Mazaris, first author on the study published in Science Advances. “We should continue to work to safeguard endangered wildlife.”

Four years ago, Mazaris, an assistant professor at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki in Greece, and his colleagues reviewed the global literature on sea turtle population trajectories to assess the effectiveness of international conservation measures. The team combed through 299 datasets spanning six to 47 years and nesting sites around the globe. They have further grouped the more recent of these data in 17 regional management units out of a total 58 such broad areas delineating particular genetically distinct populations.

“For these 299 cases, 95 have a statistically significant increase in the abundance of nests,” Mazaris said. “Only 35 have a significant decline. We get three times more increases than decreases.”

The scientists also found populations climbing in 12 regional management units.

“Even if we have a few nests or individuals,” Mazaris said, “it’s worth it to protect them because after some years, there’s potential to have a recovery of the population.”

The International Union for the Conservation of Nature lists the status of green (Chelonia mydas), hawksbill (Eretmochelys imbricata), olive ridley (Lepidochelys olivacea), leatherback (Dermochelys coriacea), loggerhead (Caretta caretta) and Kemp’s ridley (Lepidochelys kempii) sea turtles in a range from vulnerable to critically endangered. The seventh species, the flatback (Natator depressus), is unclassified because of a lack of data.

The principal threat facing sea turtles, Mazaris said, is being caught in fishing equipment targeting other animals. Poachers also harvest the turtles and their eggs for food, and plastic littering the ocean can harm them when they ingest it mistaking it for prey.

The researchers plan to look into the implications of climate change for sea turtles’ habitats and classify the severity of the risks these reptiles face around the world.

In the meantime, Mazaris said, conservation efforts should expand.

“It’s not only about sea turtles, but it’s also about the involvement of scientists, volunteers, local communities and policymakers in conservation,” he said. “If humans were able to do good for sea turtles, for other endangered species, there’s light at the end of the tunnel.”

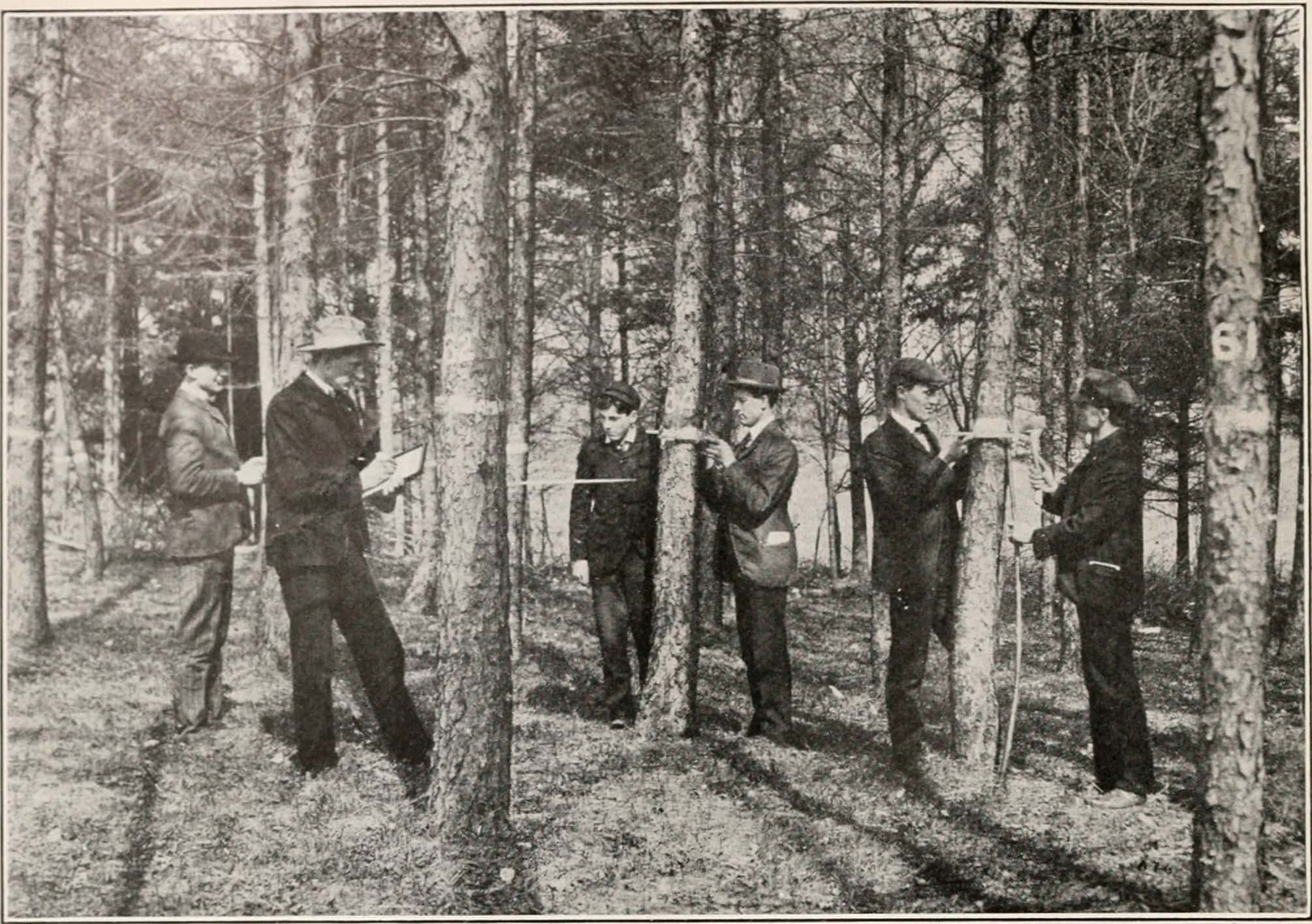

Header Image:

An adult loggerhead sea turtle swims in the breeding area of Laganas Bay, Zakynthos Island, Greece.

©Kostas Papafitsoros