Share this article

Remembering two luminaries of conservation

When Wini Kessler was a undergraduate zoology student at the University of California, Berkeley in the early 1970s, she sat in on an impromptu seminar offered by a visiting professor. He studied ants, but the book he was working on and talking about would apply evolutionary principles to human behavior.

“It was amazing to hear,” said Kessler, a TWS past president and Aldo Leopold Memorial Award recipient. “The ideas were so unusual and so fresh and so different. I just grabbed the book as soon as it came out, read it cover to cover, and signed up for a course that focused on it.”

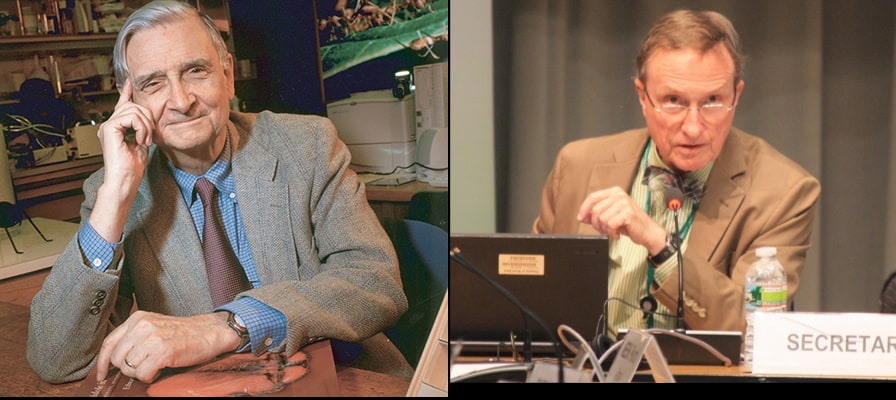

The author was E.O. Wilson, a biologist whose career would help shape the science of ecology and the public understanding of conservation. Wilson and conservation biologist Thomas Lovejoy, two luminaries who popularized the notion of biodiversity, both died within days of one another in December. Those who knew them, studied them and were shaped by their work say they left a legacy that continues to influence the field.

“The very development of the recognition of biological diversity as an important goal and target—that, to me, is something Thomas Lovejoy and E.O. Wilson represent,” said TWS Past President Bruce Thompson.

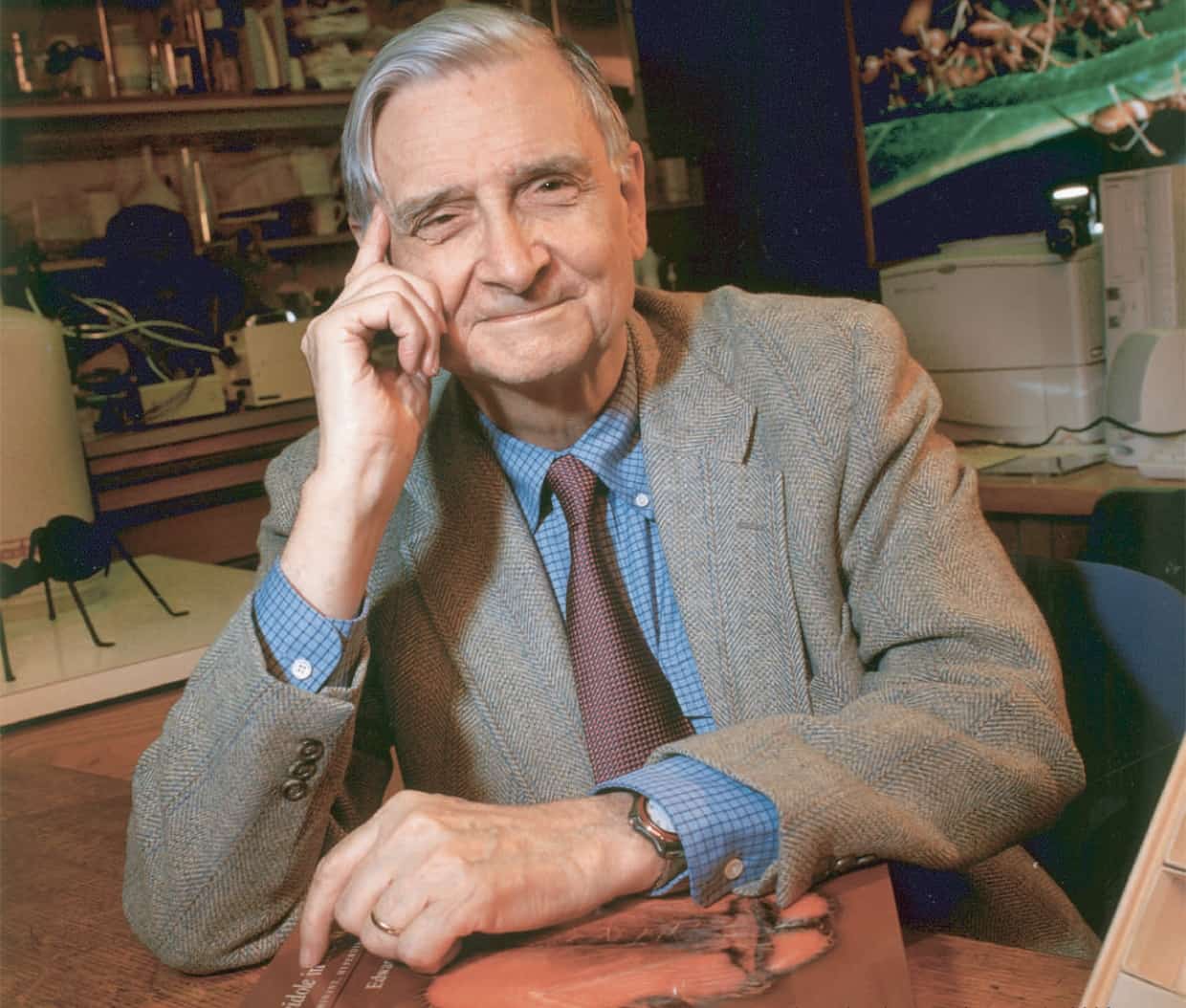

E.O. Wilson studied ants, but his impact was felt throughout the field of ecology. Credit: Jim Harrison

Thompson had studied Wilson’s work in college. But more recently, he spoke with Lovejoy when Lovejoy served as a reference for a TWS CEO candidate. A member of TWS at some points in his career, Lovejoy was very complimentary of the organization, Thompson said. But 20 or 30 years ago, the Society wasn’t as welcoming of the type of work Lovejoy was doing.

“There were still strong views about conservation as a discipline not measuring up to what TWS was,” Thompson said. For many members at the time, the Society’s game management focus didn’t square with conservation biology, but times have changed. “I would dare say the influence of Lovejoy and Wilson both have been subtle but significant to the evolution of The Wildlife Society,” he said.

From scientist to advocate

Wilson died in Burlington, Mass., on Dec. 26, at the age of 92. A two-time Pulitzer Prize winner, he was a prolific author whose work popularized the notions of biodiversity and island biogeography as well as the need for conservation. His 1992 book The Diversity of Life earned a TWS Publication Award the following year. In his later years, he championed the idea of setting aside half the earth’s land mass for nature.

“We need to map areas of the world and begin taking steps to preserve the largest possible numbers of species, opening reserve lands,” Wilson, a university research professor emeritus at Harvard University, told to a packed auditorium at the Capitol Visitor Center at a Half-Earth Day event he helped organize in 2017. But long before that, his work inspired scientists and the public to consider the importance of conservation in the natural world.

“He had a tremendous impact as a scientist before he became an advocate, and I think that’s something we can all appreciate and understand,” said Alan Wentz, a TWS past president and Leopold Award recipient.

Wentz met Wilson in the early 1990s when Wentz was the TWS president, and Wilson represented The Nature Conservancy at a memorandum of understanding signing between the two organizations. But he was familiar with his work before then.

“He made a very difficult transition from scientist to enthusiastic advocate for conservation,” said Wentz, whose own career culminated in 20 years with the conservation organization Ducks Unlimited.

“We hired a lot of new scientists and people who had been trained in the sciences and put them out in the field to work with managers and landowners,” he said. “It was good to know there were other people in the world who had come from the world of science and had jumped into the advocacy arena.”

Impact on the ground

Lovejoy, the director of the Institute for a Sustainable Earth at George Mason University and founder of the Amazon Biodiversity Center, died Dec. 22 at the age of 80. A longtime advocate for conservation in the Amazon, he is also remembered for playing a role in creating the PBS documentary series “Nature.”

“Tom had a real impact on the ground in the Amazon,” said John Organ, a TWS past president and Leopold Award recipient.

The two worked together on a project in Peru to minimize the impacts of development in the Amazon on the environment and Indigenous communities.

“He was a very unpretentious, very generous, kind individual,” Organ said. “But the reason he was so valuable in these

Thomas Lovejoy, center, joins John Organ and U.S. embassy representative Marlene Stern in Iquitos, Peru. Credit: Courtesy John Organ

efforts was that because of the prestige that he carried, we were able to get attention at the highest levels of the Peruvian government. When they heard that Thomas Lovejoy was coming down, their senior-level administration officials got involved. He commanded that kind of respect because of the legacy of his work in the Amazon. Tremendous respect.”

Lisa Muller, Southeastern representative to TWS Council, counts meeting Wilson as a highlight of her career. When Wilson spoke at the University of Tennessee, where Muller is a professor, she joined him for breakfast. The two shared a passion for biology, and as two Alabamans, a love of barbecue.

“He was such a wealth of information, but also down to earth,” she said.

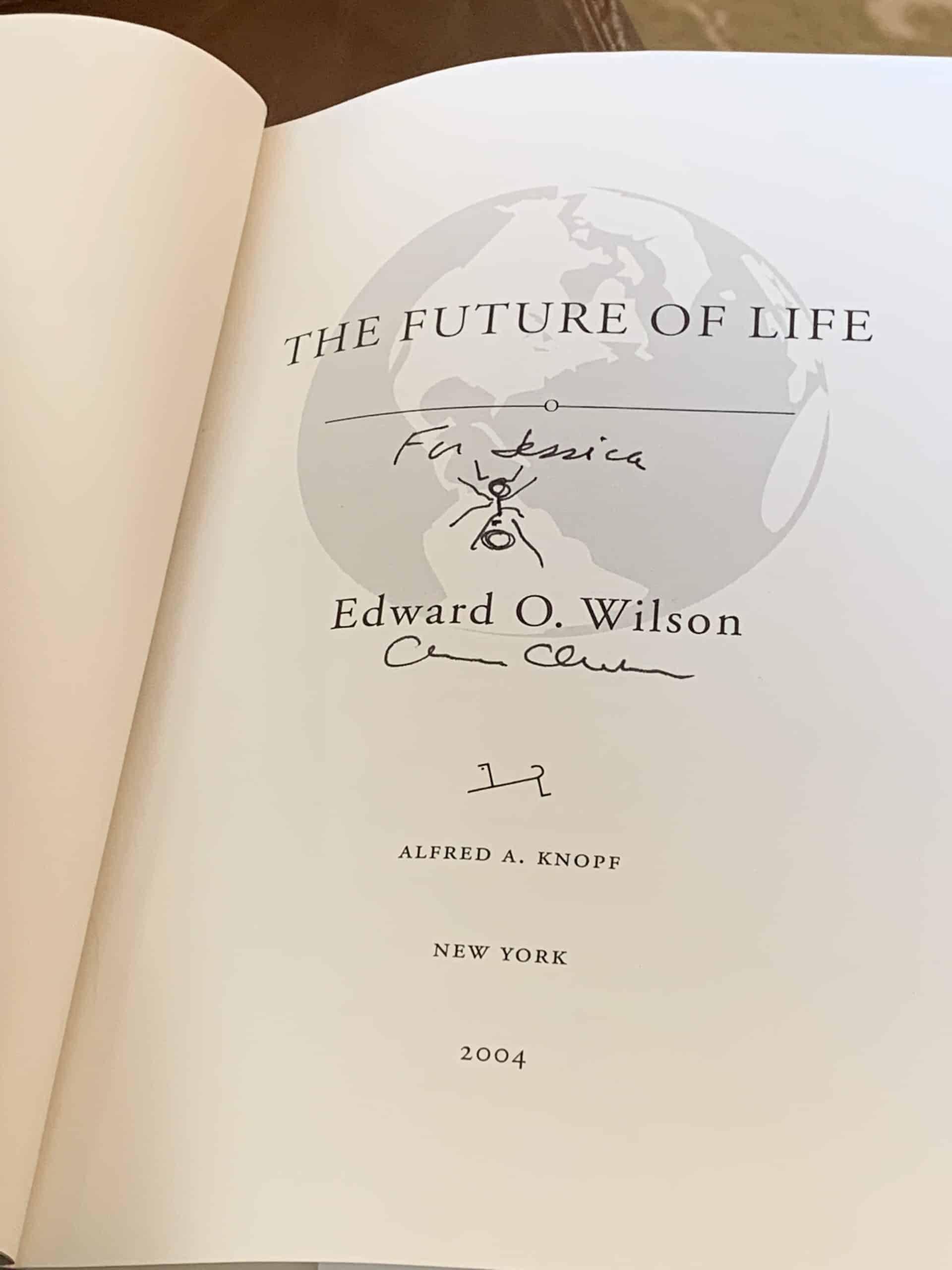

His sense of curiosity “influenced every aspect of how I approach research,” Muller said. For her, he represented an era of naturalists who were passionate about nature beyond their species of focus. But Wilson also knew ants, of course, and when she asked him to sign one of his books for her daughter, he drew a picture of an ant on the page.

“He said, ‘You know, I really don’t do this for everyone,” Muller recalled. “It is special to me. I would not get rid of it for anything.”

When E.O. Wilson signed a book for Lisa Muller, he added a drawing of an ant, the species he was famous for studying. Credit: Courtesy Lisa Muller

Header Image: E.O. Wilson, left, and Thomas Lovejoy, were pioneers in our understanding of biodiversity. Credit: Jim Harrison and the Global Environment Facility