Share this article

JWM: Two similar species have different responses to climate

Trappers in Quebec have been noticing an unusual shift on their lines taking place over the past few decades. Fishers have been on the rise, while martens have been declining.

While the two species seem similar, researchers found key differences between them are allowing one to flourish and the other to founder as the climate and landscape change around them.

“Trappers are sentinels of changes that occur in the ecosystem,” said Pauline Suffice, a University of Quebec researcher who now works with the Quebec Trappers Federation and is the lead author of the study published in the Journal of Wildlife Management. “Although they are not trained with the same methods as those used by wildlife managers, they are a kind of wildlife technician.”

The shifts the trappers had seen were taking place at the northern limit of the fisher’s (Pekania pennanti) known range and the southern end of the marten’s (Martes americana). When Suffice and her team investigated, they found changes on the ground were allowing fishers to expand.

Over the past few decades, as industrial logging has waned, coniferous forests have been giving way to deciduous or mixed forests, a change that appears to have benefited fishers. But martens thrive in coniferous forests, which tend to shield the ground from snow, making it easier for them to travel.

A warming climate is also changing the landscape. Martens are adapted to the uncompacted snow of northern latitudes, burrowing their way underneath it. But as Quebec winters see more freezing rain events and patterns of freezes and thaws, the snow is less “fluffy,” Suffice said, making harder for martens to move through.

That turns out to be beneficial to fishers, researchers found. The freezing rains can give the snow a hardened crust, which makes it easier for fishers to walk on top of the snow.

“Fisher are larger and more massive than martens,” Suffice said. They also have more fat reserves, she said, which may help them survive cold rains better than leaner martens.

“It was surprising how much rain could explain population trends,” Suffice said.

The findings come in contrast to elsewhere in North America, where marten populations appear to be increasing thanks to reintroduction programs and habitat restoration. Trappers had attributed the change in part on increased competition — or even predation — by fishers. Researchers weren’t able to measure for either of those, Suffice said, but comparing fisher and marten harvest in the 2014-2015 season with harvests from 30 years earlier, they found the changes coincided with shifting forests and changing winters.

“Trappers and biologists have a lot to gain from each other,” Suffice said, as long as both parties make efforts to adapt one another’s work methods.

This article features research that was published in a TWS peer-reviewed journal. Individual online access to all TWS journal articles is a benefit of membership. Join TWS now to read the latest in wildlife research.

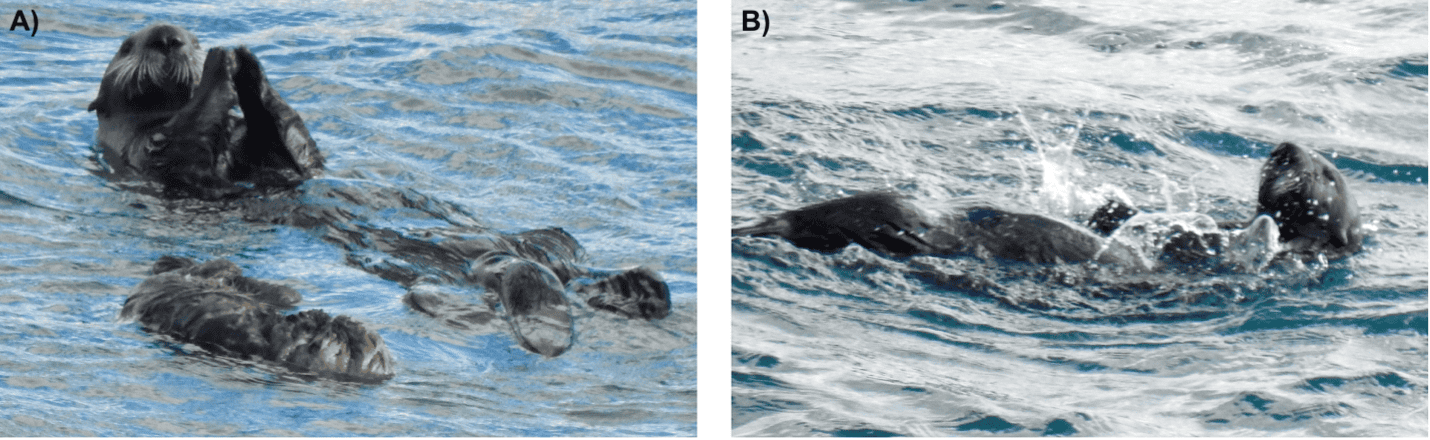

Header Image:

While martens are increasing in much of North America, they appear to be declining in Quebec.

©Pauline Suffice