Share this article

JWM: Recovered California sea lions on the decline again

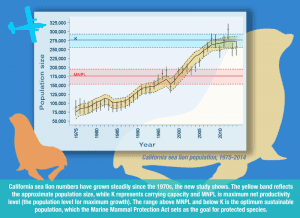

After a decades-long recovery, California sea lions (Zalophus californianus) are dwindling again due to climate-driven reductions in prey, a recent long-term study shows.

Centuries of human exploitation had once suppressed their population. The sea lions were killed for dogfood and shark bait and because they competed with commercial fisheries. But following 1972’s Marine Mammal Protection Act, California sea lions gradually recovered until recent years, when their numbers began to slip backward.

“From 1975 to 2008, the population was on a steady increase — about 7 percent a year on average,” said Sharon Melin, corresponding author on the paper published in the Journal of Wildlife Management.

Now, she said, “it’s tipping downwards. Starting in 2013, we’ve had huge warming along the West Coast, and sea lions were struggling to find food to support their reproductive activities.”

The 1972 act mandates Melin — a wildlife biologist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Alaska Fisheries Science Center — and her colleagues to monitor the California sea lion population spanning from the Mexican border to Alaska. They’ve been conducting annual ground counts on foot and aerial surveys of pups on Southern California’s Channel Islands, where most of the population breeds and summers, to calculate abundances for the pinnipeds’ different age groups. The researchers combined this data with three decades of survival estimates to model sea lion population growth from 1975 to 2014.

The California sea lion population grew to carrying capacity, but its numbers have been tailing off for several years. ©Alaska Fisheries Science Center/NOAA Fisheries

“Because of protection,” Melin said, “they got to grow with little mortality from human sources.” In 2008, they reached 275,000 individuals — the maximum number biologists believe the ecosystem can support, and their numbers continued to climb.

“It’s an amazing story of resilience,” Melin said. “They’ve had all kinds of changes in their environment, and they have weathered them.”

But, she said, recent increases in ocean temperature have reversed the upward trend. Raising surface temperatures by one degree Celsius causes a 7 percent decline in sea lions, researchers found.

“Although they’re flexible, they also are sensitive,” Melin said. “In 2013, 2014 and 2015, when the environment was completely out of whack, they had trouble adjusting.”

Higher temperatures decreased some of the sea lions’ principal prey — Pacific sardine (Sardinops sagax caerulea) and northern anchovy (Engraulis mordax) — leaving them to feed on less energy-dense market squid (Doryteuthis opalescens) and rockfish (Sebastes), Melin said. The most recent 2014 estimate put the sea lions at about 25,000 individuals below carrying capacity — a sizeable drop from the 2012 peak of 306,000 — and the research suggests their numbers will continue to shrink.

“You can’t sit back on your laurels,” Melin said. “They had a great run, and all of a sudden, it wouldn’t take much for them to drop below these milestones we hit. Long-term monitoring is important for conservation and management, and you can’t stop just because your population reached some threshold.”

TWS members can log into Your Membership to read this paper in the Journal of Wildlife Management. Go to Publications and then Journal of Wildlife Management.

Header Image: Female and juvenile California sea lions bask on the Channel Islands’ San Miguel Island. ©Jeff Harris