Share this article

Wildlife Featured in this article

- Raccoon

- Wild pig

- White-tailed deer

- Coyote

JWM: Coyotes and wild pigs may be hijacking deer feeders

Research shows that feeders may pose a risk to white-tailed deer health and prevalence

Coyotes, wild pigs and other wildlife may be keying in on wildlife feeders, posing a potential problem for people usually looking to attract deer for viewing or hunting.

“South Carolina is fairly new to coyotes. It’s fairly new to pigs,” said TWS member David Jachowski, an associate professor of wildlife ecology at Clemson University. “So the old mindset of, ‘it’s as simple as putting out corn to draw deer in’ is more complicated with these other species on the landscape.”

Wildlife feeders may have unintended consequences by increasing competition and the risk of disease in deer, and putting the ungulates at a higher risk of predation. In fact, wild pigs may even deter them altogether.

Jachowski and his colleagues were researching the effects coyotes (Canis latrans) had on white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) populations when they began to wonder whether deer feeders might be playing a role in the dynamics of the two species.

Feeding research

In a recent study published in the Journal of Wildlife Management, Jachowski and his colleagues created an experiment to find out more about the species using these feeders.

From March through July of 2021, researchers placed 15 feeders on private land spanning more than 6,000 hectares. After allowing wildlife to become acclimated to the feeders’ presence and keeping them inactive during the spring turkey hunting season, the researchers programmed the feeders to release three pounds of corn at 7 a.m. and 6 p.m. each day for two months. The team placed 15 trail cameras near feeders, and 30 elsewhere.

The team collected almost 100,000 photos just from the cameras at the feeders. With the help of Clemson undergraduate students, the team combed through the photos to determine which species were using the feeders and at what times and frequencies.

Predator problems

During the study, the team captured 15 coyotes and fitted them with GPS collars, allowing the researchers to see the animal’s normal home ranges. They determined that 10 coyotes had at least one feeder on their home turf. While the team predicted coyotes would shift their home range to be closer to an active feeder, the evidence of this was marginal.

However, Elizabeth Grunwald, the lead author of the study and research associate at the Caesar Kleberg Wildlife Research Institute, said that although she and her colleagues couldn’t prove that coyotes were learning that the sound from feeders meant prey was nearby, she suggests that had the study gone on longer, the canids would have likely picked up on this correlation.

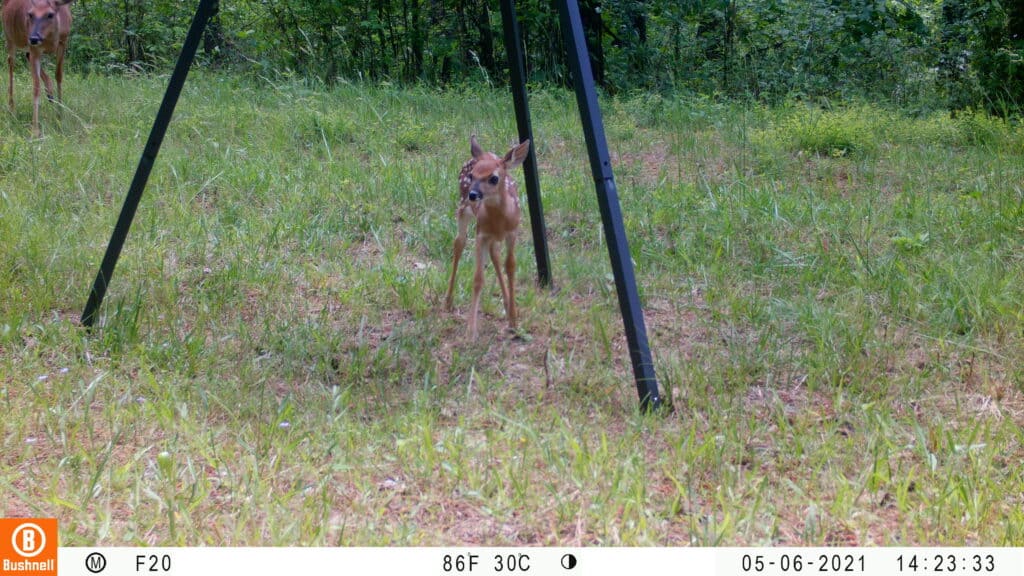

Cameras also revealed that many does were bringing their fawns to feeders in the late evenings and at night. This type of behavior makes the fawn most vulnerable to coyote predation, as they’re also most active during these hours.

“What we don’t know, however, is how far the fawns had to travel with their mothers,” Grunwald explained. “They could have traveled a long distance, or they could have been bedded nearby.”

She said that the farther they had to travel, the more risk they faced.

Pig invasion

Even though white-tailed deer can become habituated to a feeder’s schedule, the sound of corn being mechanically thrown across the ground is also often too good to ignore for wild pigs (Sus scrofa).

Like coyotes, wild pigs are relatively new to the area. For most landowners, pigs are unwelcome guests because of their destructive tendencies. Instead of helping the property’s deer herd, feeders could be exacerbating a pig problem.

The team observed that when sounders of wild pigs were surrounding a feeder, deer were noticeably absent. Grunwald suggested that this is likely the result of the typical aggression shown by pigs and their erratic behavior.

“From a deer’s perspective, why put yourself in an uncomfortable situation?” she said. “Pigs make a lot of strange, loud noises, and deer can sense that and want to avoid that area, especially because there were other things for them to eat at the time like grass and forbs.”

Because the study took place during a time when the deer had plenty of plants to browse, the pigs acting as feeder deterrents were likely not very impactful to their overall health. However, this could change in seasons or areas where resources aren’t as plentiful.

Photos also revealed another animal may be assisting pigs.

“We noticed that raccoons and pigs were somewhat working together,” Grunwald laughed—especially with large groups of pigs. “The raccoons learned how to twist off the bottom of the feeder so then all the corn would spill out for the pigs.”

Feeding disease

Deer feeders may act as disease hot spots as well. While managers haven’t yet detected chronic wasting disease in South Carolina, Grunwald mentioned that in places where it is an issue, feeders could contribute to a growing problem if infected deer are congregating at feeders. Other diseases could also jump between pigs and deer.

Overall, Grunwald and Jachowski would recommend private landowners use feeders less and that the research gathered from South Carolina should be applied to other locales, especially those with wild pigs.

Header Image: Deer feeders may put juvenile white-tailed deer at a higher risk of predation from coyotes. Courtesy of Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area/NPS