Share this article

Highly pathogenic bird flu an ‘unprecedented’ threat to wildlife

Researchers call for changes in how we manage the virus

A new strain of highly pathogenic bird flu rapidly spreading through birds is requiring wildlife managers to change their typical response to the virus. The stakes are particularly high as the spring migration raises the risk of spreading the disease even farther.

“This is a big deal—we need to pay attention to this,” said TWS member Jennifer Mullinax, an assistant professor of wildlife ecology and management at the University of Maryland. “This is not the same as all the avian influenzas we’ve dealt with in the past.”

In a perspective piece published on the wildlife disease in Biological Conservation, Mullinax and her colleagues outlined some of the shifts managers may need to make to handle the new threats presented by what they call “an unprecedented epizootic.”

Scope of the problem

Avian influenza has long been around, occurring in at least 100 bird species, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dabbling ducks and other wild aquatic birds are considered natural reservoirs for the virus. Just as the flu in humans changes and evolves every year, new waves of the disease can affect birds differently. Every so often, a highly pathogenic version of the flu infects birds, causing a larger wave of illness and death than usual.

A highly pathogenic strain of the bird flu, known as H5N1, crossed the Atlantic from Europe to North America in 2021. It quickly spread through both wild and domestic birds, likely traveling along migratory bird routes. That flu affected all major bird groups and killed more birds than previous strains. It swept through poultry operations, prompting farmers to eliminate millions of birds at facilities around the world in an effort to contain the virus.

But it has also been unusually devastating in wild bird populations. Some species are more affected than others. Seabirds that form large colonies, such as northern gannets (Alca torda) and black-billed gulls (Chroicocephalus bulleri), have been hit particularly hard.

Many scavenging bird species have also been affected, as this strain of the flu can apparently transmit from carcasses to living birds. Black vultures (Coragyps atratus) have been hit hard in some cases, with mass deaths numbering in the hundreds. Bald eagles (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) have also died from the disease, especially along the Atlantic flyway, according to research published in Scientific Reports.

One of the most affected scavenging species may be the federally endangered California condor (Gymnogyps californianus). At least 21 birds have died from the virus in 2023 alone—about 6% of the population of the roughly 330 birds that were believed to live in the wild as of the end of 2021, according to the U.S. National Park Service. The U.S. Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service announced an emergency step of approving a vaccine against the flu for use in condors.

Beyond birds

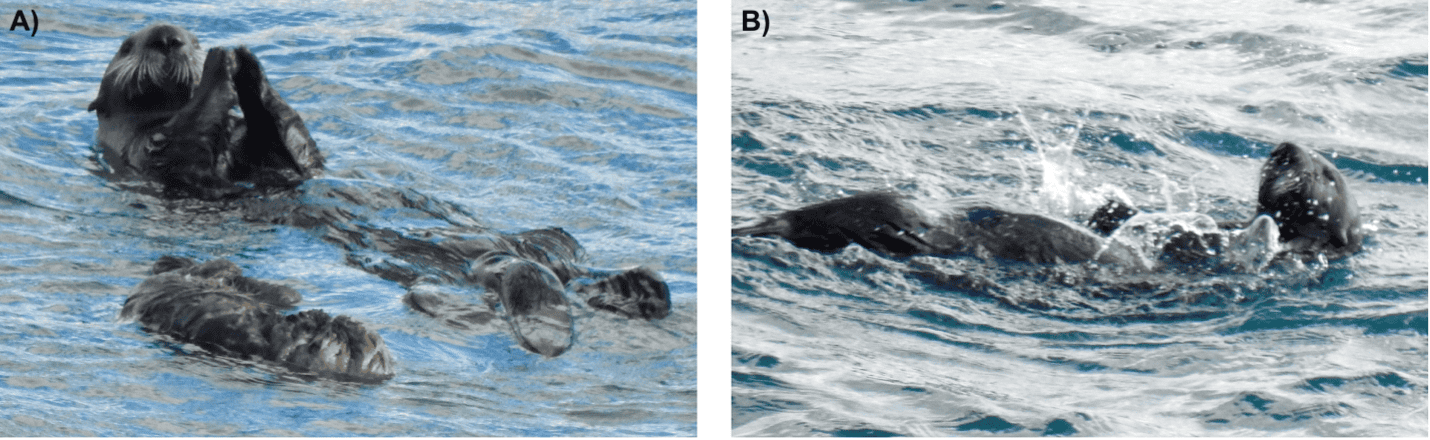

The virus has even jumped to mammals. The ones most affected so far appear to be marine mammals, including dozens of harbor seals (Phoca vitulina) and gray seals (Halichoerus grypus) off the coast of New England in 2022. Seals have also died in the St. Lawrence River in Quebec. The Center for Disease Control has reported a number of other mammal species infected, including the red fox (Vulpes vulpes), lynx (Lynx canadensis), grizzly bear (Ursus arctos) and recently a cougar (Puma concolor).

“A surprising diversity of mammalian species have died,” Harvey said.

Even humans have felt the effects of the new strain. The disease has spread from birds to a few poultry workers in Europe and Asia, though the infection hasn’t been known to jump from one human to another. The disease has mostly been mild in healthy humans that have contracted it, though a child has been reported dead in Cambodia, Harvey said. A domestic dog contracted the disease as well after eating an infected dead duck, she added.

The mortality rate of infected birds is unclear. “Birds are migrating with it,” Harvey said. “At least some animals are surviving long enough to move it along.”

Biologists fear the disease will remain for a long time. “This is very much likely to continue to become an endemic disease in birds,” Harvey said.

Management implications

Managers handled past highly pathogenic strains of the bird flu by culling birds at farms where animals had been infected with the virus. But those strains posed less of a risk of jumping to birds that might land on chicken farms during their migrations. As a result, managers will have to think of new ways to manage the problem, Mullinax said.

One obstacle to management is the sharing of data about infected birds. Different state regulations and reporting systems make it difficult for agencies and scientists to cooperate on managing a disease that doesn’t care about legal jurisdictions. A One Health approach, which involves biologists, doctors, veterinarians and other scientists working together, would help managers deal with the potential problems, Mullinax said.

It’s also important to develop new criteria for removing infected carcasses, she said. Wildlife managers need to determine how best to do this in the most cost-efficient way, especially since, as Harvey noted, the problem will probably be a long-term one.

“We’re going to have think about this differently,” Mullinax said.

Header Image: Northern gannets are among the species that have seen large die-offs from highly pathogenic bird flu. Credit: A S