Share this article

Frogs recovered from fungal disease have altered microbiomes

Even after frogs clear the infection caused by chytrid fungus, their microbiomes don’t recover, which could have implications for managing the disease.

Microbiomes include all of the bacteria, fungi and viruses that live on or inside an organism. The vast majority of these germs are not pathogenic. “Traditionally, we have thought of germs, which is a layman’s term for microbes, as harmful,” said Andrea Jani, an assistant researcher at the Pacific Biosciences Research Center and Department of Oceanography at the University of Hawaii at Manoa. “More and more, we’re finding microbes on animals are absolutely critical for their health and development.”

Jani and her colleagues already knew from past research that being infected with Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (Bd), the fungus that causes chytridiomycosis in amphibians, can alter frogs’ microbiomes. But they wondered if bacteria would change once the frogs had been cleared of the fungal infection.

“Amphibians are declining faster than any other group,” she said, adding that chytrid is one of the main reasons. “There is hope the bacteria on the skin of frogs or these microbes might play a protective role.” But first, she wanted to find out how being treated for the fungus affects their possibly protective microbiome.

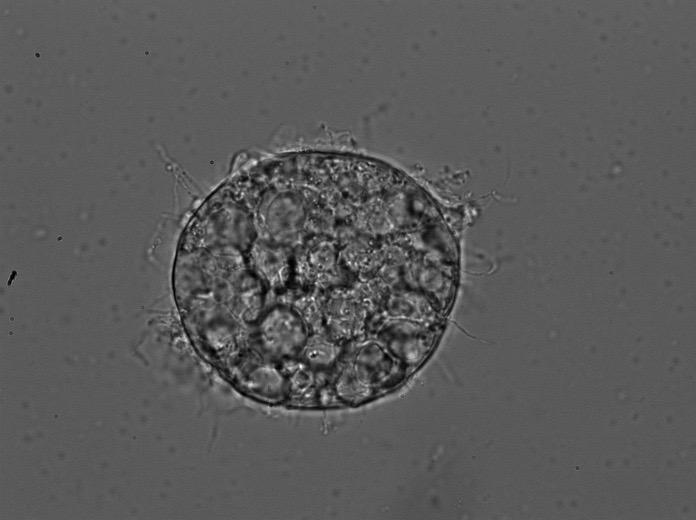

A microscopic image of the fungus Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (Bd), which causes chytrid in amphibians. Credit: Andrea Jani

In a study Jani led published in the ISME Journal, she and her colleagues examined the microbiomes of mountain yellow-legged frog (Rana muscosa), an endangered species in the Sierra Nevada in California. As part of a conservation effort, the group brought wild frogs into the lab and infected them with Bd; a group of control frogs was not exposed to Bd. The researchers later treated all the frogs with an antifungal drug to clear them of Bd infection. They collected skin swabs before, during and after the infections to detect what their microbiome looked like by using genetic sequencing. “If you can clear them of the infection, would the microbiome recover as well?” she wondered. “Would it go back to normal?”

Their results told them which bacterial “species” (technically, amplicon sequence variants) were there and what their relative abundances were. After reviewing their findings, they determined that the microbiomes didn’t return to their original composition, even after the frogs recovered from the fungal infection.

“Most of the metrics didn’t show that they recovered when we cleared the frogs of the infection,” she said. It could be her team didn’t wait long enough. They waited three weeks, Jani said, but “it’s possible they recover, just very slowly,” she said.

A researcher holds a healthy looking yellow-legged frog. Scientists found their microbiomes are altered even after they are cleared of the chytrid fungus. Credit: Andrea Jani

Jani and her colleagues don’t know yet what this change in microbiome means for its functionality. “When you have a change in species in the bacterial community, that might or might not change functions in the community,” she said. They did find that changes in the microbiome are linked to greater weight loss in frogs, which may suggest the microbiome change can be detrimental.

These findings may be useful in conservation of the species and management of the disease. This experiment served dual purpose. While Jani focused on microbiomes, her collaborators are testing if exposing frogs to Bd in the lab as they did in this study could act like a vaccine to immunize the frogs. They are using microchips to track frogs and test if vaccinated individuals have better survival after they’re released back into the wild.

“I think what it tells me in terms of current actions is, it’s really important to quantify the efficacy of a treatment,” she said. Researchers sometimes struggle with not treating a control group when there is a possibility that the treatment can help the frogs survive a major threat, but controls are important in knowing if a mitigation strategy is actually useful.

Another conservation implication, she said, is in developing probiotics — culturing helpful bacteria and putting them on frogs that can get the disease.

Header Image: A healthy looking yellow-legged frog in Sierra Nevada, California. Image Credit: Andrea Jani