Share this article

Wildlife Featured in this article

- Gadwall

- Mallard

Counting ducks with drones

End-to-end AI automated drone system for waterfowl detection, counting and reporting

Above the glittering lake water, researchers envision a drone drifting in slow, deliberate arcs, its camera sweeping the water above bobbing birds like a searchlight. Seconds after it passes, the fan of a laptop on the tailgate of a pickup truck kicks on. As the drone lands safely back into the hands of the operator, a full report is generated with species counts, mapped habitats and analyzed trends.

For decades, estimating waterfowl abundance and habitat meant long hours in and out of the field. Researchers trekked across the landscape on foot or in expensive small planes and processed data for hours afterwards. Accuracy varied, influenced by factors ranging from weather to observer experience and the process could take weeks or even months to yield results.

But now, wildlife managers are working to create a smooth artificial intelligence technique that can count ducks accurately based on drone photography similar to the hypothetical scenario described above.

“AI is great at tedious, very time-consuming jobs—we can automate it and do what takes a lot of time nearly in real time,” said Yi Shang, a professor in engineering at the University of Missouri. “We get counts in a day with a regular desktop.”

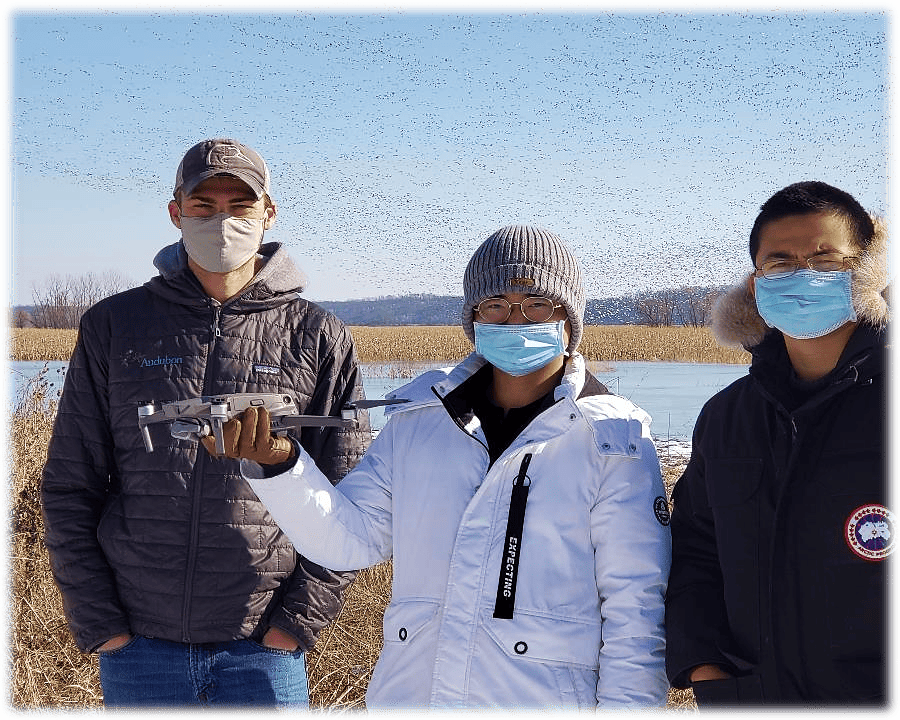

In a study published recently in Drones, Shang and his collaborators designed and tested in the field an end-to-end automated system aimed at detecting migrating waterfowl species in Missouri. The system segments habitat into different types using drone imagery and deep learning, a type of AI that develops pattern recognition based on the data it is given.

To create a system that could handle the diverse field conditions experienced in Missouri, researchers went out into the field and collected drone images of waterfowl under a variety of environmental conditions and across different altitudes, habitat types and sky conditions.

Researchers used the images to create and test multiple deep learning models, including several You Only Look Once (YOLO) models, to detect and count mallards (Anas platyrhynchos), gadwalls (Mareca strepera) and teal species. These models can detect and identify multiple objects in an image. Other deep learning models determined six habitat types in the images: open water, cropland, harvested crop, wooded, herbaceous, and other. The system also used the birds’ locations to check where images overlapped, keeping the chance of counting the same bird twice at about 5%. Overall, the tool correctly identified birds and habitats more than 80% of the time and up to 95% under ideal conditions.

“AI is really helpful and for this case, it’s not replacing jobs,” said Shang. “It’s helping people to do their jobs better and process large amounts of information efficiently.”

Waterfowl such as mallards, gadwall and teals are economically valuable game birds where population estimates are crucial to informing management strategies such as hunting seasons and wetland restoration priorities. Additionally, waterfowl can be an indicator of wetland ecosystem health, reflecting the underlying conditions of the ecosystem.

Shang and his collaborators hope that this system will give wildlife managers a faster, more accurate way to monitor waterfowl populations, giving managers better information to guide conservation decisions.

Header Image: In Missouri, gadwall migrate between the southern United States and Mexico and their breeding grounds in the northern U.S. and Canada. Credit: USFWS Mountain-Prairie