Share this article

Burrowing crabs may help marshes tackle sea level rise

Burrowing crabs may be speeding up the process in which marshes adapt to sea level rise as a result of climate change.

“I actually kind of think it’s a beautiful mechanism,” said Sinead Crotty, a project manager at the carbon containment lab at Yale University and the lead author of a study published recently in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

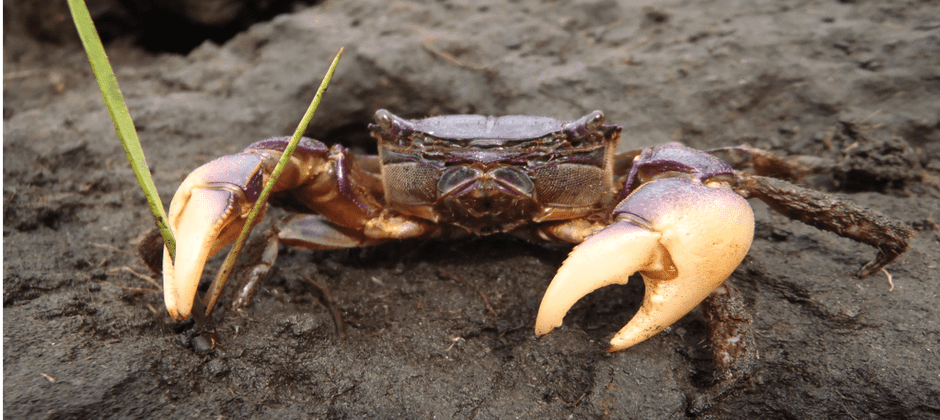

The purple marsh crab (Sesarma reticulatum), a type of burrowing crab, makes its home in eastern United States salt marshes. The crabs dig into the ground beneath the water, eating the roots of marsh grass and other vegetation. That process destabilizes the marsh, as the grass holds the environment in place and makes it more resistant to tidal erosion.

Larger blue crabs (Callinectes sapidus) usually control purple marsh crabs. But overfishing of the larger predators has opened the door to the purple marsh crabs overexploiting marshes in many areas in the northeast U.S.

Climate change is exacerbating the burrowing crabs’ expansion. Rising sea levels due to climate change and storm surges are opening up more habitat for the purple marsh crabs throughout the East Coast.

The invertebrates can only burrow into the substrate at a certain depth and hardness. If the mud is too soft, their burrows collapse and trap them inside. If the turf is too hard, they can’t dig into it. Crotty said that as the sea level rises, the crabs can quickly exploit marsh vegetation they couldn’t reach earlier as it softens up. In the southeast U.S. marsh sites, this activity allows the tidal marsh areas to drain water more quickly.

“It’s a rapid geomorphic evolution, where you can see in real time where the crabs allow the marsh to drain more water to keep pace with sea level rise,” Crotty said, adding that she’s seen the heads of tidal creeks erode by as much as 6-10 meters per year.

As the crabs clear the marshes, these pathways likely allow larger predators like fish, bigger crabs and even birds to come in and eat them and other invertebrates.

The rapid loss of some ecosystems may not work out for all species that rely on these marshes if they can’t survive the short-term destruction of the habitat, though. In fact, Crotty said some species may become locally extirpated due to the combination of sea level rise and marsh crab activity.

“It has really negative biological consequences,” she said.

But some of those predators may benefit in the longer term. When the species prey on marsh crabs, they then bring the crabs’ numbers back down again and allow new marsh grass to grow. So while this may have initial consequences, the crabs clearing out the grass and allowing the creeks to drain allows the ecosystem to recover more quickly as the sea level rises.

For some species, they may actually benefit in the short term, like wading birds and seabirds that feed on the marsh crabs and other invertebrates that are exposed as the grass is removed.

“The ecosystem has to endure some trade-offs,” Crotty said, adding that new marsh grass ecosystems are created farther inland as a result over the course of about five years. “This can happen over the course of, for example, one PhD dissertation.”

Header Image: Marsh crabs may speed up the ecosystem changes due to sea level rise. Credit: Ser Amantio di Nicolao