Share this article

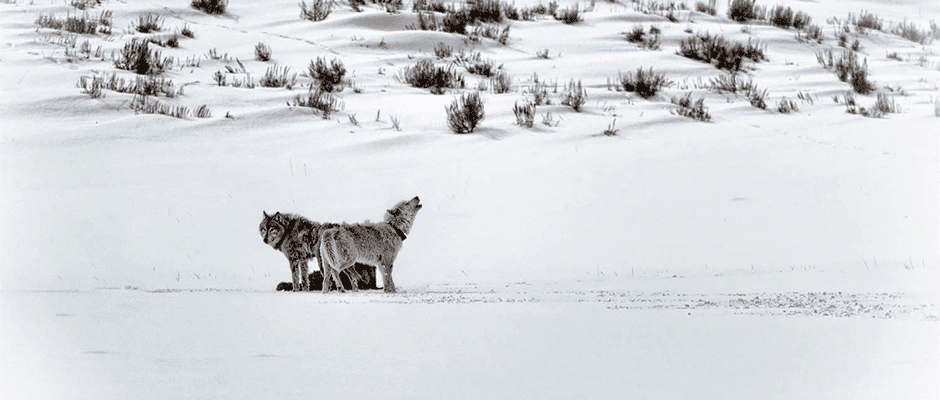

Study shows Yellowstone wolves’ impact on streams

When hydrologist Robert Beschta went to Yellowstone National Park, he was looking for the effects that elk (Cervus canadensis) were having on river systems as they browsed down willows on the banks.

He had seen it before in river systems across the West where large carnivores had been removed or displaced. Whether it was the Gallatin River in Montana or the Virgin River in Utah, elk and deer reduced the willows to nubs. As browsing increased following large predator loss, the vegetation was scoured, allowing the stream banks to erode.

That had been the case in Yellowstone, too, but over the years, he found, things were changing. Vegetation was returning to the banks and the streams were recovering. The banks weren’t eroding anymore. Flood plains were forming. Canopies were returning overhead. Birds and beavers (Castor candensis) were coming back. Beschta realized the reason only partly had to do with the elk.

Elk numbers in recent years were decreasing in Yellowstone’s Northern Range, he said, and as they decreased, the vegetation returned. The main reason for the improving vegetation, he found, appeared to be the reintroduction of gray wolves (Canis lupus).

“Overall, results were consistent with a landscape-scale trophic cascade, whereby reintroduced wolves, operating in concert with other large carnivores, appear to have sufficiently reduced elk herbivory in riparian areas,” wrote Beschta and his colleague William Ripple, both professors at Oregon State University’s College of Forestry, in a recent study published in the journal Ecohydrology.

Beschta and Ripple aren’t the only ones to document wolves’ transformative effect on Yellowstone’s ecosystem. Writing in the journal Mammalogy, TWS member Mark Boyce recently documented a range of effects in the park, from reducing elk numbers to increasing bison (Bison bison) populations, due to a trophic cascade triggered by the wolves’ return.

The Oregon state professors looked at willows over a 13-year period along two forks of Blacktail Deer Creek, first in 2004 — nine years after wolves were reintroduced in the park — and again in 2017.

During their first visit, Beschta said, the elk in previous years had browsed willows down to knee height. The loss of vegetation allowed the stream to widen. When they returned last year, the willows had grown to over 9 feet tall and large canopies had returned, helping the stream — and the ecosystem — to recover.

“What we see appears to be a general reversal of impacts,” he said, “but it will take time for a lot of these to work their way out.”

One place the recovery is not happening is along major valley bottoms, such as in the Lamar Valley, Beschta said, where increased bison populations continue to heavily browse vegetation along the river banks.

Yellowstone’s recovery makes it an interesting test case for what happens when large carnivores return, he said. But is it the only one? With the return of wolves in places like Canada’s Banff National Park, Beschta said, similar vegetation recovery also appears to be happening there.

Yellowstone’s improving stream health is especially striking, he said, since it is occurring at a time when climate change ought to be making it harder for native vegetation to survive.

“The reintroduction of wolves has caused this improving of plant communities across much of the Northern Range,” Beschta said. “We are bucking the climate change pattern that would normally tell us that plants should be doing worse.”

Header Image: A recent study found the reintroduction of gray wolves in Yellowstone National Park has improved the health of streams. ©Scott Kublin