Share this article

AI anticipates spring bird arrival as Arctic climate shifts

As temperatures rise and the Arctic climate becomes more unpredictable, birds could be following the shifting spring and showing up to nest off schedule. Researchers recently developed machine learning approaches to analyze sound recordings to estimate when songbirds will arrive for the breeding season. They hope the technology can also be harnessed to assess climate change’s effects on other wildlife in other places.

The techniques did a good job of replicating the work of humans on the ground, said Ruth Oliver, first author on the study published in Science Advances. “Deploying them in the future would be important for understanding how climate change might be impacting the timing of bird arrival on breeding grounds,” she said. The timing has implications for the birds’ reproductive success and population, she said. This new approach “could help us tease out” which environmental conditions most affect changes in their timing.

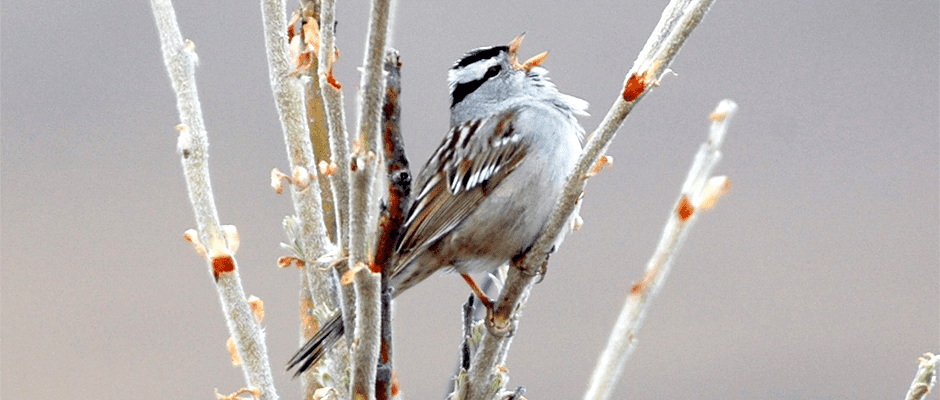

A graduate student at Columbia University, Oliver and her colleagues aimed to investigate how increasing variability in the onset of the Arctic spring related to when migratory songbirds flew in to reproduce. They worked with 1,200 hours of vocalizations by many songbird species, including Gambel’s white-crowned sparrows (Zonotrichia leucophrys) and Lapland longspurs (Calcarius lapponicus), which are common on this landscape.

Microphones picked up the sounds at four locations on the Alaska North Slope between early May and mid-July from 2010 to 2014. After categorizing tiny clips based on whether the birds could be heard in them, the scientists fed these sounds to an algorithm. They taught it to not only recognize the birds’ calls as a human would, but to predict the birds’ arrival based on how many calls they heard.

“We have a totally unsupervised approach that doesn’t rely on any listener input,” Oliver said, “and that corresponded well with the arrival dates estimated by the on-the-ground survey.”

She plans to apply the technique to a wider region and distinguish among a variety of species. With a traditional approach, that kind of research takes many hours to process, she said. “The cool thing about ours is that you can do it in remote locations over a larger spatial and temporal scale.”

Header Image: A Gambel’s white-crowned sparrow perches on a woody Arctic shrub. ©John Wingfield