Share this article

Endangered Mexican sea turtles at risk of bycatch

On a Baja California Peninsula beach, sometimes over 1,000 sea turtles a year unexpectedly wash up dead because local fishermen incidentally entangle them offshore. Analyzing these animals’ bones, researchers discovered that these coastal shelf waters provide long-term habitat for an East Pacific population of endangered green sea turtles (Chelonia mydas), which makes them more vulnerable than previously thought to becoming bycatch in these heavily-fished waters.

“We initially assumed it was by chance that green turtles were getting caught in this fishery, that they were traversing from one foraging lagoon along the shore to another one and happened to pass through this high-bycatch area,” said Cali Turner Tomaszewicz, first author on the study published in the Marine Ecology Progress Series. “This work highlighted that this is a primary foraging area for green turtles, so it does warrant conservation and changes to fishing practices.”

Intensely harvested through the 1970s, the East Pacific green turtle population — found feeding in lagoons from Mexico to California — experienced enormous declines. Mexico banned the turtle harvest in 1990, protected breeding sites and suppressed poaching, and the decimated population began exhibiting a rise in nesting females in the current decade. But off the western coast of the Baja Peninsula, these turtles remain at risk by unintentional capture in artisanal fishing equipment.

Then a doctoral candidate at the University of California, San Diego, Turner Tomaszewicz searched for clues in 35 turtle humerus bones from Playa San Lázaro to piece together where the reptiles went as they developed. Her team used skeletochronology, a technique based on skeletal growth rings, similar to tree rings, that has been used on sea turtles since the 1980s, Turner Tomaszewicz said.

“We can get a record of growth and age — 20 years of data from a single bone,” she said, a history that other means don’t provide.

The biologists used the rings’ chemical signatures to determine where the turtles inhabited and what they ate. They expected to see the turtles shift from offshore feeding early in life to nearshore feeding as they aged. Instead, they found they continued to feed offshore throughout their lives — a phenomenon she said is being seen more and more in green turtles worldwide. The rich forage available helps them grow faster, Turner Tomaszewicz said, but it puts them in the heart of a heavily-fished area for much of their lives. “It’s this great foraging area with high risk,” she said.

Fortunately for the turtles, fishing communities have modified their operations to decrease bycatch, Turner Tomaszewicz said, “so by adjusting the time of year as well as fishing gear they use, they’ve been able to reduce the number of turtles getting caught in nets and washing up on shore.”

The scientists are now investigating different rates of maturation in green turtles that forage in different locations, including offshore versus nearshore. They’re also applying skeletochronology to green turtles across the West Coast, and they recently produced a similar paper featuring the method on juvenile North Pacific loggerheads (Caretta caretta) found in the same Baja California waters.

“It had long been known loggerheads were using this area, so the efforts, motivation and groundwork was already laid to make changes to reduce bycatch,” Turner Tomaszewicz said. “All the work protecting loggerheads was helping green turtles as well, making improvements to fisheries so small-scale fisheries can continue to thrive, but sea turtle groups can also continue to thrive.”

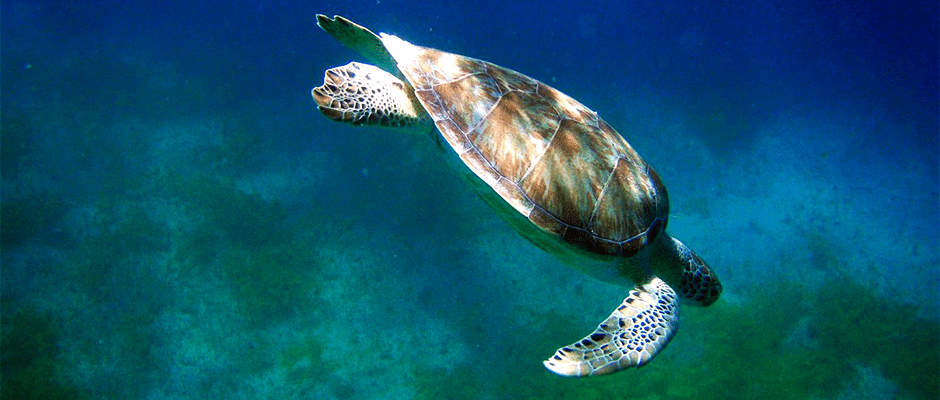

Header Image: Off the coast of the Baja Peninsula, green sea turtles spend much of their time in the open ocean, putting them at risk of being snagged by fishing equipment. ©Cali Turner Tomaszewicz