Share this article

Old nautical charts inform reef conservation in Florida Keys

When British navigators charted the global waters they sailed centuries ago, they didn’t intend to record ecological information that would have a bearing on marine conservation. A recent study tapped into this historical resource, however, and discovered that coral reef loss in the Florida Keys has been more severe than previously thought.

“We found half of the original observations in the past isn’t coral habitat today,” said Loren McClenachan, lead author on the paper published in Science Advances. “Ninety percent of areas eliminated was nearshore.”

Prior research found an 80 percent decrease in well-known coral reef habitat throughout the Caribbean over the last four decades, said McClenachan, an assistant professor of environmental studies at Colby College.

“There are other areas that used to be coral reef habitat that aren’t considered to be that anymore,” she said. “In the Keys, it’s a 75 percent decline in live coral in areas that have coral. If 50 percent of those were gone by the time we started studying it, it’s probably a bigger number than we’re coming up with looking at recent studies.”

The British Empire mapped coastal areas as it expanded worldwide. Some maps noted the presence of coral to keep sailors from crashing in the shallow Caribbean and help them intercept Spanish ships carrying riches out of the Americas. Researchers examined two charts from 1774 and 1779, which illustrated 143 occurrences of coral around the archipelago from the Lower Keys up to Key Largo, and compared them with modern ocean floor habitat data to determine where those recorded coral reefs persisted.

Coral is in serious trouble due to multiple factors, McClenachan said. Climate change is warming and acidifying oceans to levels this animal can’t tolerate. Reefs are also vanishing because of physical disturbances from local development, including shoreline hardening, dredging and sedimentation. Overfishing compromises the resilience of reef systems since coral die if too few fish graze the algae growing on it.

“This is a shifting baseline story,” McClenachan said. “Knowing corals used to be in a bigger geographical area than we realized is helpful in knowing where we could expect those coral to be again. It sets a restoration goal.”

McClenachan plans to dig further into the archives to learn more about reefs around the world through colonial maps, which other scientists had already used to investigate alterations to forest ecosystems.

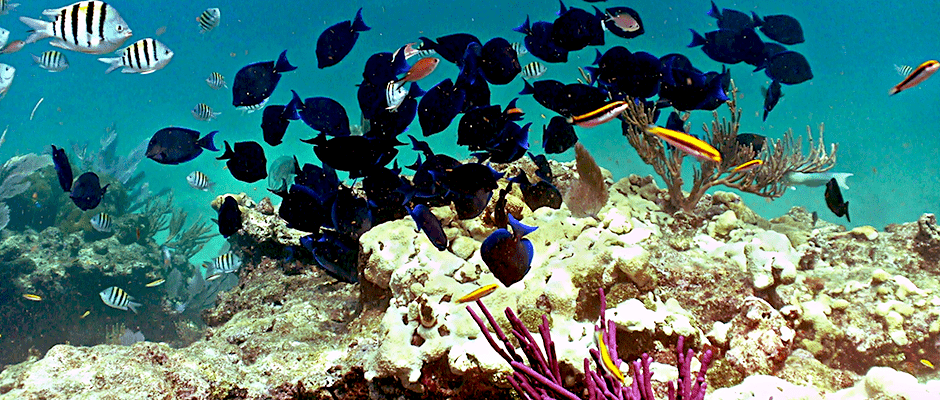

Header Image: Fish congregate on the coral reef at the Looe Key Sanctuary Preservation Area in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary. ©Phils1stPix